Gupta and Greensill prompt steel jobs crisis

- Published

Sanjeev Gupta, who has been called the "saviour of steel"

The crisis engulfing the UK's third largest steel maker, its financier, and the government now tasked with saving thousands of jobs, is a complex tapestry of strands, none of which are in themselves particularly shocking, but woven together make up a very murky picture of the relationship between industry, finance and government.

As the BBC revealed on Thursday morning, the government is bracing itself for taxpayer intervention as it all unravels.

The saviour-turned-sinner steel magnate, the maverick billionaire now bust financier, and a former UK prime minister, are the principal characters in a story in which the jobs of 5,000 workers and the future direction of UK industry is arguably at stake.

For years, Sanjeev Gupta arrived like magic on the scene whenever UK heavy industry was in big trouble.

He bought up steel plants in Scunthorpe, Stocksbridge, Dalziel, Newport etc - promising to invest in greener processes while saving jobs. He was hailed by unions and feted and courted by politicians.

Where he was getting the money was unclear - partly because his growing empire was a collection of businesses under the Gupta Family Group (GFG) Alliance banner.

They were interconnected but, importantly, not consolidated. There were no financial statements that described the group as a whole.

British Steel's works in Scunthorpe

The accountants he used for his various businesses were usually minnows in the accounting world. Not what you would expect for a business which grew to 35,000 employees worldwide and £15bn in sales.

The trick was to use tomorrow's money to pay today's bills. Lex Greensill, originally a sugarcane farmer from Australia had, he thought, perfected the way to do this.

Gupta would bring Greensill Capital the invoices he had sent his customers - which they might have up to 180 days to pay - and Greensill would give Gupta the money immediately.

Sometimes Gupta would sell bundles of these invoices to investors with Greensill taking a fee for arranging the deal. The more invoices Gupta could generate, the more bundles he could sell, and he used the proceeds to buy more businesses which generated even more invoices to bundle and sell.

This suited Lex Greensill perfectly, who wanted to show the business was growing so he could sell Greensill Capital itself for billions.

The music abruptly stopped when the buyers of these bundles realised they were very exposed to one big invoice generator. Gupta accounted for over half of all Greensill's business.

Investors and insurers got cold feet and Greensill collapsed rapidly into administration - switching off Gupta's funding. The businesses' reliance on each other destroyed them both.

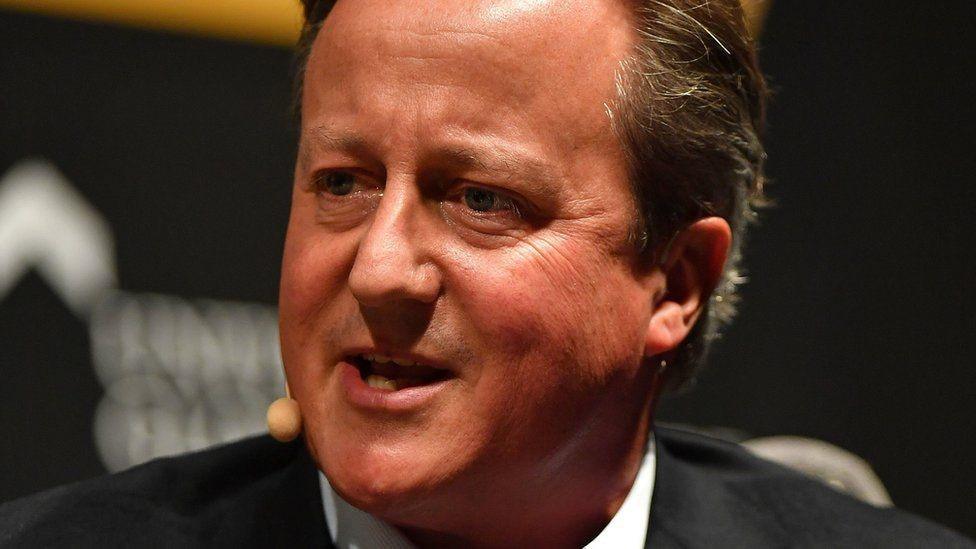

Finally, the juiciest but perhaps the least significant titbit is the involvement of a former prime minister.

David Cameron was a paid adviser to Greensill and stood to make millions from Greensill's success, thanks to stock options in a company that was estimated to be worth over £5bn just a couple of months ago.

Former British prime minister David Cameron was a paid advisor to Greensill Capital

The fact that he reportedly texted Rishi Sunak personally to press the case for Greensill to get greater access to government coronavirus-related loan guarantees has provoked outrage and a call from Labour for an investigation.

It seems a particularly brazen intervention by a particularly high-profile figure - but the truth is, former politicians get paid to lobby on behalf of businesses all the time. They are not paid for their fascinating political anecdotes - they are paid to gain political access and influence.

On this occasion, the lobbying didn't work and the Treasury rebuffed the approaches of Mr Cameron on behalf of Greensill.

But the government cannot sidestep its seemingly inevitable next request - using public funds to stop Gupta's empire collapsing with the loss of 5,000 jobs - some of which are in former red wall areas that fell to blue in the last election.

The playbook from the last steel crisis has been dusted off - British Steel was kept on life support by government guarantees to the Official Receiver for five months until Chinese firm Jingye eventually bought the firm - despite heavy interest from guess who? - yep, Sanjeev Gupta.

This situation is much more complex.

The intricate web of financial engineering between Gupta, Greensill and the investors who bought their bundles of invoices has strong echoes of the financial crisis.

It will take months, if not longer, to sort out who has a claim on whom and for what. The five months British Steel was in government intensive care cost the UK taxpayer hundreds of millions of pounds.

Minister of State for Business, Energy and Clean Growth Kwasi Kwarteng has promised to procure more steel made in the UK for big transport and defence projects

What some may find surprising, is that the kind of intercompany financing that has imploded here, is not a regulated activity.

As an official at the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) told the BBC, while they recognise there is potentially some painful real world fallout in terms of jobs, the finance bit of this concerns sophisticated people who have deep pockets and teams of advisers.

Unlike the financial crisis, its collapse is not considered "systemically important". But socially, strategically and politically it is very important.

Government officials said over the weekend they are still "hoping for the best, but preparing for the worst". Efforts at GFG Alliance to find a lifeline continue, but there is little optimism in the air.

The Business Secretary Kwasi Kwarteng has set out his stall in a way that would make it hard to let collapse.

First, he has promised to procure more steel made in the UK for big transport and defence projects, and second, he has prioritised decarbonising steel production - technology in which Gupta's firms have the UK edge - a fact Mr Kwarteng recently highlighted.

Remember, in political currency, every car, aerospace, steel and defence job seems worth 10 times as much as every job in retail or services.

When the intersection between industry, finance and the government goes bad, the taxpayer is rarely untouched.

Mr Cameron has so far declined to comment on the issue.

- Published19 March 2021

- Published18 March 2021

- Published9 March 2021