Shopping in 10 minutes: The new supermarket battleground

- Published

Weezy was the first app-based rapid grocery delivery service to launch in the UK

"I'm amazed it hasn't been done earlier by some of the big supermarket chains," says satisfied customer Kiran Wylie.

"To be able to deliver supermarket-quality food within 10 minutes is very enticing."

The 28-year-old communications manager lives in Hackney, one of the London boroughs that form the new battleground of grocery shopping.

If you live in the right part of the country, you can now call on a whole raft of app-based systems that promise to bring you groceries within 10 to 15 minutes.

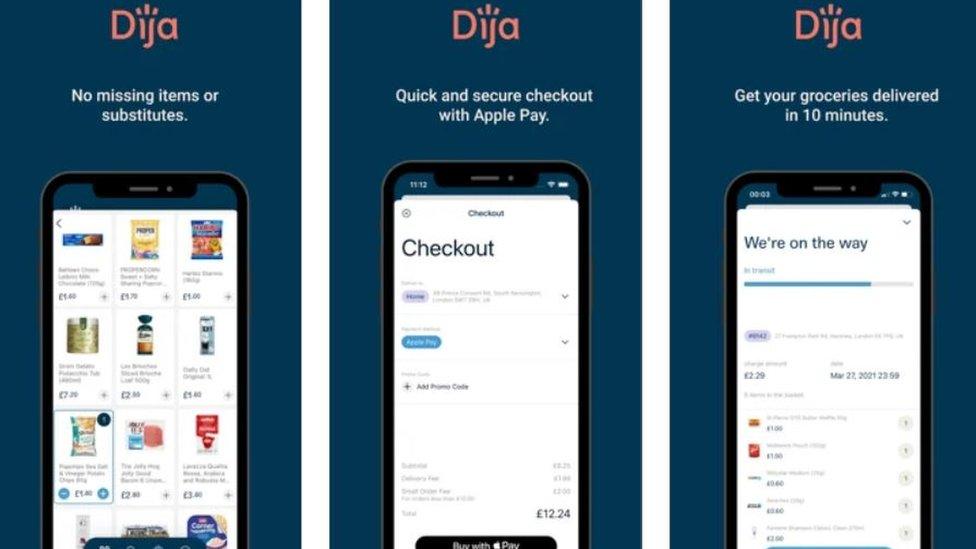

Agile start-ups with names such as Weezy, Gorillas and Dija are promising instant deliveries with no substitutions. Kiran has tried all three, but likes Dija best because he finds its app is easier to navigate.

"Where I live is quite far away from the nearest shop and I wanted something that's quite quick and has a good selection of products," says Kiran.

Some of these services have come to the UK from overseas, including Turkish-based Getir, which offers goods "from iceberg lettuce to ice-cold beer" and proclaims on its website: "Minutes matter - life is hectic."

Gorillas, which hails from Berlin, claims to be "faster than you" in what it calls the "last-mile delivery of essential human needs".

Others are homegrown and are keen to take on foreign markets. London-based Dija, which says it provides "the best grocery experience with none of the hassle", is planning to expand not only into other UK cities, but also into Europe.

Life is hectic, says Getir

Dija set up shop just three months ago, having secured $20m (£14.5m) of seed funding from venture capital firms. It has already hired 80 people and covers about half of London.

It charges a flat fee of £1.99 ($2.80; €2.30) for delivery, with every order supplied by its own fleet of riders on electric bikes, directly employed by the company.

It pledges that if the goods don't arrive in 10 minutes, you get three months' worth of free deliveries.

So how do they do it? Chad West, Dija's director of brand marketing, says it's all down to a hyper-local, data-driven model.

"Every area where we operate has its own fulfilment centre," he says. "If it's a large borough and we need to open a second one, we do that."

Each fulfilment centre stocks about 2,000 items, in a carefully chosen selection tailored to the demographics of the area.

Dija's publicity promises no missing items or substitutes

Asked how Dija can make a profit, Mr West says that as with all tech firms, "becoming a profitable business is not an immediate priority" as it prefers to invest in growth initially.

However, he says the delivery fee "pretty much covers the cost of fulfilling an order" and that Dija buys its groceries wholesale to sell retail: "We're not just going to a supermarket and filling a basket."

Mr West realises that Dija is one firm in a crowded field, but doesn't see those rival start-ups as a problem.

"We're not competing with those guys," he says. "The reality is, we're competing against Tesco, Asda, Sainsbury's. That's where the customers are going to come from."

Although the growth in rapid grocery delivery apps may seem to be a product of the pandemic, the first such firm to launch in the UK, Weezy, was conceived as far back as September 2019.

And chief operating officer Alec Dent, who co-founded the firm with chief executive Kristof Van Beveren, wasn't afraid of getting his hands dirty when the pair set up their first base in Fulham.

"I did 400 deliveries myself in the early days," he says. "That was very important, because you understand what it's like to deliver."

Gorillas is a Berlin-based start-up now coming to the UK

Mr Dent also has a background in the start-up sector, having worked as vice-president of operations for car subscription firm Drover.

But he is keen to play down the idea that Weezy is a tech firm, describing it as a grocer and retailer that happens to use an app.

Weezy's website doesn't refer to "warehouses" or "fulfilment centres", but calls its premises "stores". And they have store managers, who can manage their selection of goods and make changes.

"We work with local brands and butchers and bakers," says Mr Dent. "Our customers like the convenience of online, but they also want to support their local shops."

Large baskets

Weezy also places emphasis on fresh produce, rather than frozen or convenience food. And although ordering quick deliveries on your mobile phone might seem the preserve of the young and tech-savvy, it says it has loyal elderly customers too.

"Groceries are something every age bracket uses," says Mr Dent. "It's not like takeaway, which is much more geared to people in their 20s and 30s."

Weezy charges a delivery fee of £2.95. When asked about profitability, Mr Dent says that many customers are using them not just for the odd item, but for bigger shops as well.

Weezy is available in Brighton and Bristol as well as London

"People shop large baskets. It's a significantly higher spend than Deliveroo, which helps," he says.

"If you suddenly need a lemon, because you've run out and you've got people coming for dinner, you can do that, just as you might run out to the local store.

"But we find that on average, the quantity people buy and the amount they spend is more than that."

So far, Weezy has 100 employees spread across 15 sites, including Brighton, Bristol and now Manchester. It plans to open 150 more this year.

Supermarket sweep

The existing players, including Morrisons and the Co-op, have been teaming up with food delivery firms to get their products out faster.

Sainsbury's, for one, has just announced it is expanding its partnership with Deliveroo, meaning that about 30% of the population can now choose from some 1,000 Sainsbury's products within 20 minutes.

Deliveroo is helping existing supermarkets fight back

Deliveroo is not confining its operations to the UK. Last week, it announced that it was partnering with Carrefour stores in France, Belgium, Italy and Spain.

However, Deliveroo has a different business model from the other app-based services, since it relies on the "going to a supermarket and filling a basket" system so derided by Dija.

Meanwhile, Ocado is planning to expand its Zoom service, which has been operating in West London and promises groceries in 30 minutes.

The retail industry likes to talk about "fast-moving consumer goods", but as retail analyst Kate Hardcastle puts it, we now have fast-moving consumers.

"For a lot of people, grocery shopping is a means to an end, not a very exciting part of life, so they want to automate it," she says.

Even in the longer term, she adds, these rapid grocery delivery services are unlikely to cover the whole country. "It's more suited to intense heavily built-up areas." But even so, it "creates an appetite for things to be faster", she says.

Ms Hardcastle sees the firms as "pioneers trying to break the boundaries" and says they will certainly have the big supermarkets scratching their heads.

Not all of these pioneers will survive, but as she says, these are times in which notions that were once far-fetched can swiftly become part of everyday life.

"The magic is when you find the sweet spot of what the customers want and what they are willing to pay for," she says.