How market research reveals what you really think

- Published

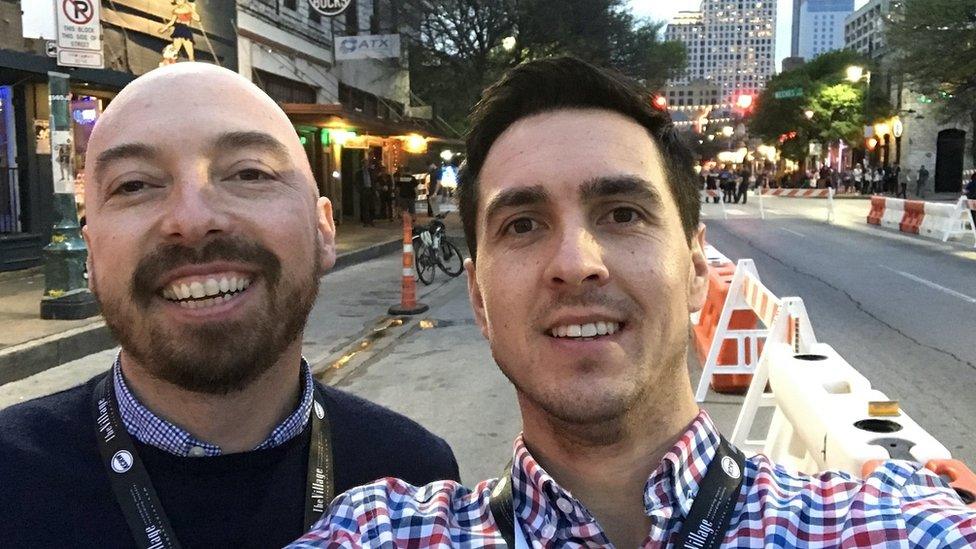

Carl Wong (left) and fellow founder of Living Lens, David Woods

Traditional market research, based on clipboards and questions, has a glaring weakness, according to Carl Wong, who has worked in the industry for more than 20 years.

He says people cannot answer some questions honestly because they are not aware of their own deep underlying motives.

"We are all influenced by things we're not able, or willing, to reflect on at the time a purchasing decision is taken or when we answer a survey question," says Mr Wong.

That gap in our understanding is being filled by a data-rich world that generates masses of information about our inner desires through tracking cookies and a host of other clues we leave behind as we trek across websites that pique our interest.

In addition, market researchers can access massive amounts of computing power and data storage using low-cost cloud computing services, which offer data processing and storage that can be quickly scaled-up or down, depending on the customer's needs.

This tech-fuelled revolution is shedding light on how we conceal our innermost urges from ourselves - for example why we are drawn to the exploits of certain public figures and celebrities.

Jason Brownlee researches consumer behaviour on a grand scale, fuelled by the social media data explosion and the resulting caches of big data.

Jason Brownlee, founder of Colourtext

The founder of Colourtext, a data analysis and consumer insights specialist, is based in a village in the Lake District. But he can follow all our movements from his rural idyll. "People leave digital footprints behind them," he says.

He has studied news consumption patterns, using Artificial Intelligence (AI) and cloud computing to peer into the trail people left as they viewed 100,000 news articles online.

"Once they click onto a page we begin to see a pattern emerging. We can't do this in any other way than using AI and the cloud, you'd be in your grave before you'd finished reading all those articles!"

This produced startling insights into how figures such as Boris Johnson and Meghan Markle are really perceived. The power of big data has broken down traditional categories that the market research industry used to define our taste.

Insights about how public figures like Duchess of Sussex are perceived can be gleaned from big data analysis

"The rule was that people who go to show business stories tend not to be interested in politics," says Mr Brownlee.

His deep dive into the readership habits of 18 different UK online news outlets, including BBC News Online, dashed this assumption and uncovered attachments that had eluded previous researchers.

"I discovered a group of people who read about celebrities. The top of their list is Meghan Markle. But they also read about Boris Johnson. They are not normally interested in political stories, but Boris has a much broader reach than just politics."

Pouring big data into the cloud and scrutinising it with AI suggested that the Prime Minister is seen by many as a celebrity.

These connections defy accepted market research segmentation, and only number-crunching in the cloud can spot them. The pay-as-you-go model means cloud power is flexible and affordable says Mr Brownlee. "You can dial up or dial down the computing resource and you get the ability to do interesting things through online AI programmes."

Market researchers can understand human behaviour as never before by trawling through this trove of data.

Facial expressions can now be put under a data analysis microscope for first time, says Mr Wong, who works for US analytics software house Medallia after selling them his Merseyside-based consumer insights business, Living Lens.

His technology measures a face at multiple points with different patterns emerging depending on the emotions it expresses. These patterns alter with age, sex and race. Show AI software enough examples of these patterns and it can begin to establish what a person is feeling.

Del Taco, the US fast food restaurant chain, turned to Mr Wong when the company updated its décor and menus but wanted to align these changes with customer feedback.

Mr Wong's team stepped in with a survey app that allowed Del Taco diners to answer questions via video on their smartphones. "We captured that video and analysed hours of feedback from customers looking at their language and their sentiments as they spoke. It gave us a much richer view than a traditional survey."

This data was all streamed into the cloud for analysis, which exposed the underlying emotions the customers felt as they were quizzed about their meal.

"Oil tankers" of data are being analysed, says Jon Puleston

The scale of data that can be manipulated in the cloud has grabbed the attention of the whole market research industry. Jon Puleston analyses online material for consumer research giant Kantar and revels in this new element: "We are producing oil tankers of data and the cloud is allowing us to refine it."

By plunging into the cloud with its own software Kantar confirmed that we are incapable of being truthful to market researchers trying to establish what really floats our boat.

"Talking to a camera is a very effective tool, but what people say is often miles apart from what they feel, there are so many unconscious factors at play."

Specialist software pointed at filmed responses taps into these unconscious factors via clues such as tone of voice and facial expression. This tells Mr Puleston we are very hard on ourselves over our guilty pleasures, such as watching a rom-com.

When we are asked to rate a film our natural instinct is to mark down a lightweight movie although we've really enjoyed it and lie about how we liked one with intellectual content. We might be giving the serious show a four star rating, but in truth we only got emotionally involved with the rom-com story.

Kantar applies AI to a bank of human emotions recorded on film and assembled in the cloud and demystifies our real sentiments. This unlocks the ingredients of a Hollywood crowd-pleaser.

Market researchers may have given up knocking on our front doors with their clipboards, but technology is allowing them to get inside our heads.