Gigafactories: Europe tools up against US and Asia as a car battery force

- Published

Northvolt's gigafactory is 125 miles south of the Arctic Circle

Surrounded by a forest of tall green pine trees, 125 miles south of the Arctic circle, a giant electric battery factory is rapidly taking shape on a site as big as 71 football pitches.

The project will be a gigafactory, a term coined by Tesla founder Elon Musk to describe his first high-volume plant for producing lithium-ion electric battery cells, deep in the Nevada desert.

Startup Northvolt, co-founded by two former Tesla executives, is in Skellefteå, a much chillier location, in northern Sweden.

But from here, as well as a base in Västerås just outside Stockholm, it is hoping to provide a quarter of Europe's electric batteries, as demand for electric vehicles surges amidst the global race to cut carbon emissions.

By 2030, 40% of all new cars sold will be electric according to the latest forecast by the investment bank UBS, rising to almost 100% of the new car market by 2040.

"If you look at the agenda for all the automotive manufacturers to actually make those electric cars, the amount of cells that you'll need to access, is going to be humongous," says the plant's manager Fredrik Hedlund.

Northvolt plant manager Fredrik Hedlund

Although many of the imposing grey buildings are yet to have much equipment installed, Mr Hedlund is confident everything will be in place in time for production to start by the end of 2021.

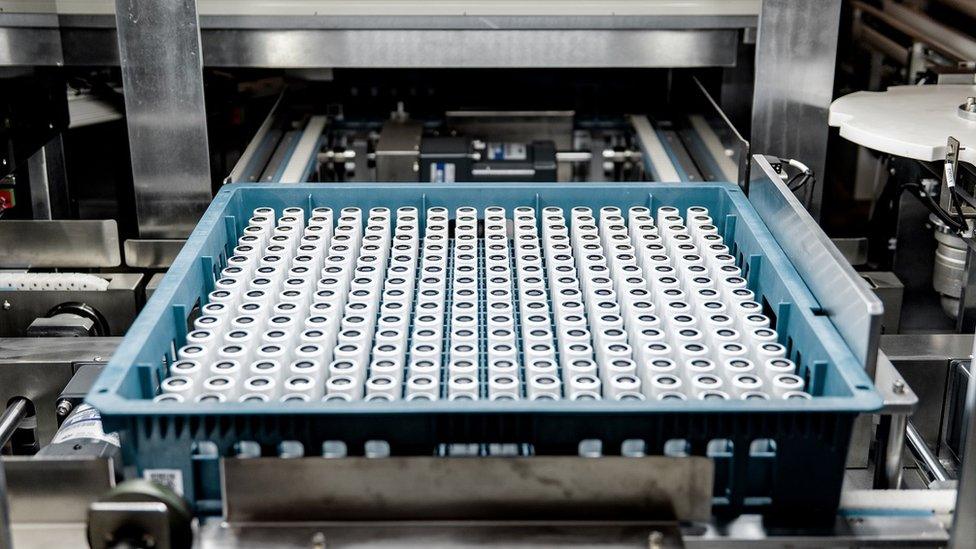

In its first phase Northvolt aims to make enough batteries to power almost 300,000 electric vehicles a year, but with the potential to raise that figure to 1 million.

The company has already received a $14bn order from Volkswagen to produce its batteries for the next decade, and has plans for a long-term partnership with Swedish truck and bus maker Scania.

It recently announced that it had raised another, external $2.75bn (£1.94bn; €2.26bn) to fund its expansion.

"We are building a totally new industry that hasn't really existed, especially in Europe, at this scale," says Mr Hedlund, striding across the high-security site in a neon yellow jacket. "I think, not only myself but a lot of people, think that this is the coolest project in Europe right now."

In northern Sweden at least, there hasn't been a more-hyped project since miners literally struck gold 100 years ago. But for Northvolt, water is now the region's most valuable asset as the manufacturer seeks to make "the world's greenest battery", by ensuring its production techniques are as climate-friendly as its product.

Renewable hydroelectric energy from the Skellefte river will fuel the battery-making process on the site, which includes using giant mixers to combine lithium, cobalt and other metals, and drying out active material in rows of industrial ovens, which have just been installed. Local access to raw materials and plans for an on-site battery recycling plant will also keep down the plant's own carbon footprint.

There are still gaps in the green loop though, with some employees commuting weekly by plane from other Swedish cities and many others driving non-electric cars to the site.

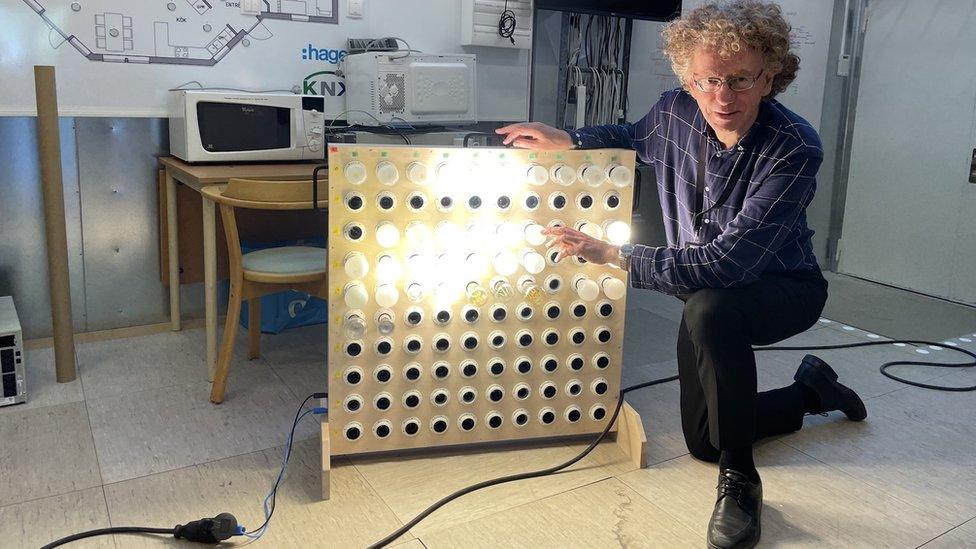

Math Bollen, a professor in electric power engineering, at Luleå University of Technology

But the firm's efforts are far from greenwashing, according to Math Bollen, a professor in electric power engineering, at Luleå University of Technology's campus, on the other side of the Skellefte river. "It's certainly going to be more green than what others are making," he says. "They [have] taken a very good first step - let's hope others follow it."

While Northvolt's green credentials (and perhaps its picturesque and far-flung location) have put the Swedish project in the spotlight, the company is one of a growing number of European companies making inroads in the gigafactory industry, which, alongside Tesla, has largely been dominated by Asian players.

Norwegian energy company Freyr is planning a gigafactory fuelled by wind and hydro energy in Mo i Rana, a remote coastal town close to one of the country's most popular ski resorts. Daimler and BMZ have already set up energy-efficient gigafactories in Germany. French start-up, Verkor, is planning a facility north of Toulouse.

The UK is running slightly behind its northern European neighbours, although a 235-acre (95 hectare) site in Northumberland is set to become the first operational gigafactory by late 2023. Run by a firm called Britishvolt (which has nothing to do with Sweden's Northvolt despite its similar name), it will be fuelled by hydroelectric energy sourced from Norway, as well as offshore wind farms.

"We're certainly sprinting very hard now to catch up with the others," says the company's chairman Peter Rolton. He has ambitious plans to not just "give the UK its own local supply of electric vehicle batteries," but produce enough products to plug gaps in other European countries as demand for electric cars grows.

Demand is booming for lithium ion batteries

London-based Sandy Fitzpatrick, who monitors vehicle trends for global technology analysis firm Canalys, is confident there will be plenty of room in the market for the new rush of European players.

She says a plentiful supply of locally sourced batteries will be good for the electric car market, but it will also be an important branding strategy for European carmakers.

They're facing increasing pressure to offer genuinely sustainable business models after the so-called diesel-gate scandal, which saw Volkswagen caught using illegal software to manipulate the results of diesel emissions tests.

"Saying that their whole supply chain has components that are green and sustainably manufactured is a very good message to go out to consumers with," says Ms Fitzpatrick, "as opposed to using components that are flown in and have a high carbon footprint because they are transported from all over the world and are produced with very coal-intensive methods".

But she believes European car and battery manufacturers will continue to face tough competition from major Asian brands, many of whom have already set up their own gigafactories in the EU. These include LG Chem, which has a plant in Poland, and Samsung SDI and SK Innovation who've built factories in Hungary.

"They've got the experience. They've got the market know-how... and more importantly, they've got the capital," says Ms Fitzpatrick. "Battery manufacturing is hugely capital intensive. So they're going to enter Europe with deep pockets."

If European gigafactory firms want to thrive against this competition, she says they'll need continued investment, alongside practical support from national and regional governments to optimise trading conditions, and provide "perks [and] incentives to help them along".

Skellefteå has a boomtown feel to it

Back in Skellefteå, Northvolt does seem to be ticking those boxes. The company has secured substantial funding, including a $350m loan from the European Investment Bank, and financial support from the state-funded Swedish Energy Agency as well as the German government, following the Swedish startup's multimillion dollar deal with Volkswagen.

The company is also collaborating closely with universities in the region, and has strong backing from the local municipality, which lobbied Northvolt to choose Skellefteå as a base because of it's hydropower, even before the startup had it on its shortlist.

"It's a win-win for both of us," says the town's Deputy Mayor Evelina Fahlesson. "We want to be a role model in the green transition... and we have an ageing population, so we need to have a growing labour market."

The battery plant is a "win-win" says Skellefteå Deputy Mayor Evelina Fahlesson

Northvolt's presence is expected to create around 10,000 new jobs in the region, and the city is already investing in thousands of new energy-efficient homes, electric buses, winter-friendly cycle lanes and even an electric plane project, all designed to create a green and liveable city for the new influx of national and global talent.

There is already something of a "boom town" atmosphere, with buzzing waterfront bars, shiny new shopfronts and an almost-finished cultural centre which will be one of the world's tallest wooden buildings.

"It will get harder to find an apartment because prices are going up," says 20-year-old student Gabriel Kitebwini, who's enjoying a drink on the riverside. "But I think it is good. Because we get more new people from around the world travelling, coming into our city - we get a bigger city."

"It's a new atmosphere in the municipality," agrees Ms Fahlesson. "Before, people moved out of Skellefteå, but today we see them moving back."