UK needs millions more charging points, says car industry

- Published

- comments

The UK needs to set a binding target for building battery factories and install millions more charging points for electric cars, the industry says.

The Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT) says ambitious policies over the next decade could create up to 40,000 high-skilled jobs.

But it warns failure to take action could be disastrous for the car sector.

SMMT fears the potential loss of around 90,000 posts and worsening regional inequalities across the country.

The SMMT's chief executive, Mike Hawes, said that without the right backing, UK businesses would become "consumers not producers, spectators not innovators… lead and we succeed, follow and we fail".

"If ambitious words were currency, the UK would indeed be rich," he said. "Give us the tools, and we will finish the job."

Later this week, Japanese manufacturer Nissan is expected to announce plans for a new so-called Gigafactory to build batteries at its manufacturing base in Sunderland.

Mr Hawes said that under current plans the UK will have 12 gigawatt hours (GWh) of battery production by 2025, whereas Germany will have 164GWh.

The expected announcement from Nissan, he said, would be "a real vote of confidence… but we need a lot more than that".

A spokeswoman for the government said: "We are committed to ensuring the UK continues to be one of the best locations in the world for automotive manufacturing and are dedicated to securing gigafactories to support the auto sector's transition to electric vehicles.

"We continue to work closely with investors and vehicle manufacturers to progress plans to mass produce batteries in the UK."

She added that the UK already has more than 23,800 public charging points including 4,450 rapid devices - one of the largest networks of rapids in Europe.

"We are working closely with local authorities to rollout the electric vehicle revolution, with £1.3bn investment for electric vehicle infrastructure which will support drivers across the country," she said.

More gigafactories needed

A report, written for the SMMT by consultants Public First, sets out a range of proposals that it claims would secure the future competitiveness of the automotive industry - a sector which it claims contributes £15bn to the UK economy, and employs around 180,000 people.

The shift to electrified vehicles, it says, is the biggest challenge facing the sector. The sale of new cars powered only by petrol and diesel is due to be outlawed by 2030 in the UK, while hybrids will be banned five years later. Other European governments have also set targets for phasing out conventional vehicles.

Nissan is expected to announce a new gigafactory in the UK

To meet demand for new electric cars, the report says, the government should commit to creating so-called gigafactories - giant battery-building plants - with a capacity of 60GWh by 2030.

At the moment, the only British factory making the kind of batteries needed for electric cars on a large scale is Envision AESC's plant in Sunderland. It has an output of around 2GWh, and is used to provide power packs for the Nissan Leaf, which is also produced in the region.

The Japanese carmaker is widely expected to announce later this week that it will expand this partnership, and invest heavily in a new gigafactory, which will initially have a capacity of at least 6.5GWh.

Stellantis, the global car company which owns Vauxhall, is expected to announce within the next few weeks whether its plant at Ellesmere Port will have a long term future. It has been considering whether to build electric cars at the factory in Cheshire.

Alison Jones, the UK managing director of Stellantis suggested a decision by the company about where it will build a new gigafactory in Europe was central to its discussions with the government about the plant's future, which she said were "ongoing".

"That's why it's so important for the government to make their statements and their actual investments in UK manufacturing manufacturing", she said.

The influential green group Transport and Environment recently warned that even this would amount to "a tiny fraction of the 474GWh of production at 17 sites across Europe, for which funding has already been secured".

The group suggested that the UK risked being left behind as other countries invested more rapidly in electric car production. It also expressed doubts that a number of other projects, including start-up Britishvolt's ambitious plan for a 35GWh factory in Northumberland, would happen without more pressure from the industry itself.

Plea for government support

The SMMT's report, meanwhile, makes a number of other recommendations. It says there is a need for at least 2.3 million new charging points to be set up around the country by 2030.

This would, it suggests "ensure that all drivers - especially those without driveways - have the confidence to invest in the latest low emission technologies, investment that will not just support a healthy domestic market, but which will underpin mass market automotive manufacturing in the UK".

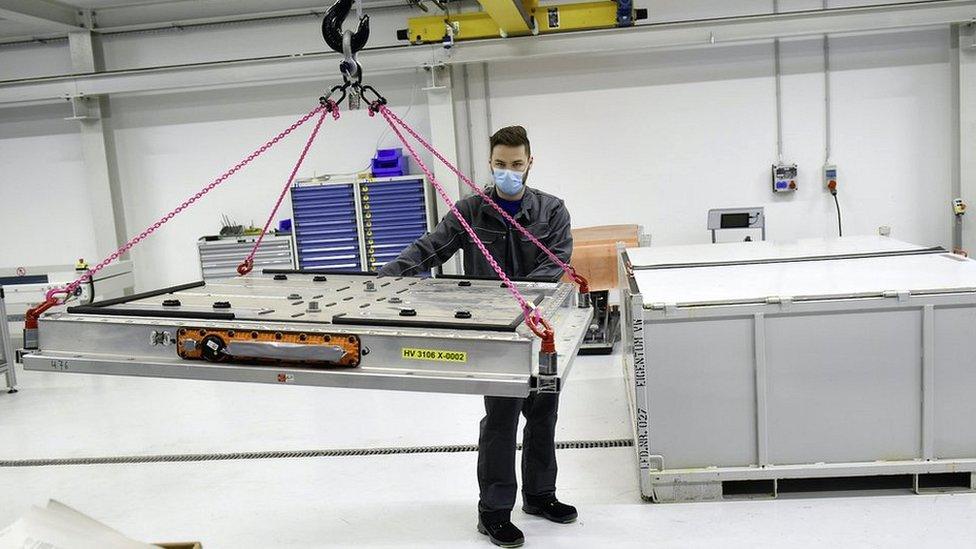

Power packs for the Nissan Leaf are currently produced in Sunderland

It also calls for the introduction of a "build back better fund" from the government to support manufacturing jobs and reduce costs, a commitment to developing and deploying connected and automated vehicle technology and a review of taxes affecting the sector.

The stakes, the SMMT says, are high. The correct strategy, it claims would see the sector transitioning to a zero emissions future, with ambitious global trading terms.

This, it suggests, could create 40,000 well paid and highly skilled jobs by 2030 - and would have a significant impact in the car industry's traditional heartlands, such as the West Midlands and the North East.

But without such a framework, it claims, the UK's automotive industry risks falling into a decline, resulting in the loss of some 90,000 jobs.

The majority of them would be lost outside London and the South East, thereby increasing regional inequality.

Related topics

- Published28 June 2021

- Published16 June 2021

- Published27 April 2021