Electric cars: What will happen to all the dead batteries?

- Published

The world will have to work out what to do with millions of disused car batteries

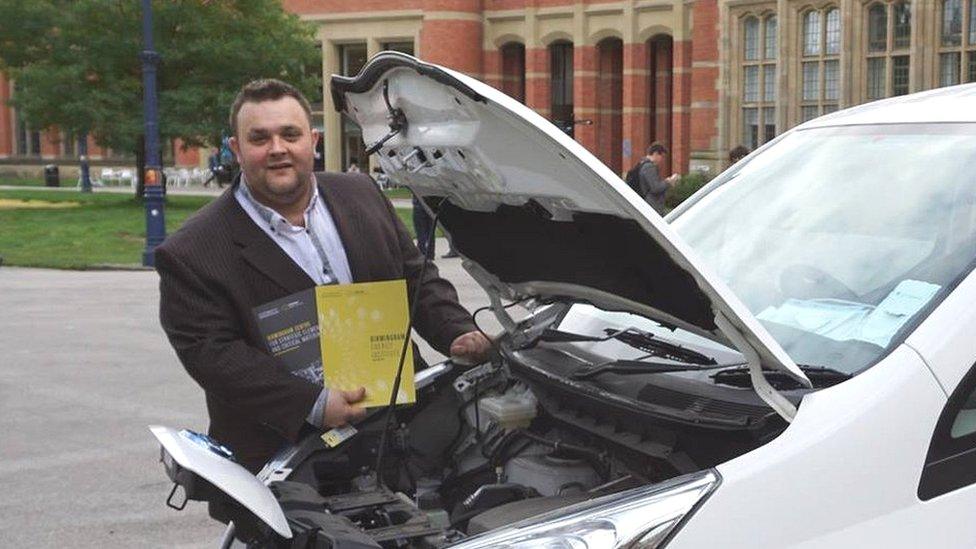

"The rate at which we're growing the industry is absolutely scary," says Paul Anderson from University of Birmingham.

He's talking about the market for electric cars in Europe.

By 2030, the EU hopes that there will be 30 million electric cars on European roads.

"It's something that's never really been done before at that rate of growth for a completely new product," says Dr Anderson, who is also the co-director of the Birmingham Centre for Strategic Elements and Critical Materials.

While electric vehicles (EVs) may not emit any carbon dioxide during their working lives, he's concerned about what happens when they run out of road - in particular what happens to the batteries.

"In 10 to 15 years when there are large numbers coming to the end of their life, it's going to be very important that we have a recycling industry," he points out.

While most EV components are much the same as those of conventional cars, the big difference is the battery. While traditional lead-acid batteries are widely recycled, the same can't be said for the lithium-ion versions used in electric cars.

EV batteries are larger and heavier than those in regular cars and are made up of several hundred individual lithium-ion cells, all of which need dismantling. They contain hazardous materials, and have an inconvenient tendency to explode if disassembled incorrectly.

"Currently, globally, it's very hard to get detailed figures for what percentage of lithium-ion batteries are recycled, but the value everyone quotes is about 5%," says Dr Anderson. "In some parts of the world it's considerably less."

Recent proposals from the European Union would see EV suppliers responsible for making sure that their products aren't simply dumped at the end of their life, and manufacturers are already starting to step up to the mark.

Nissan, for example, is now reusing old batteries from its Leaf cars in the automated guided vehicles that deliver parts to workers in its factories.

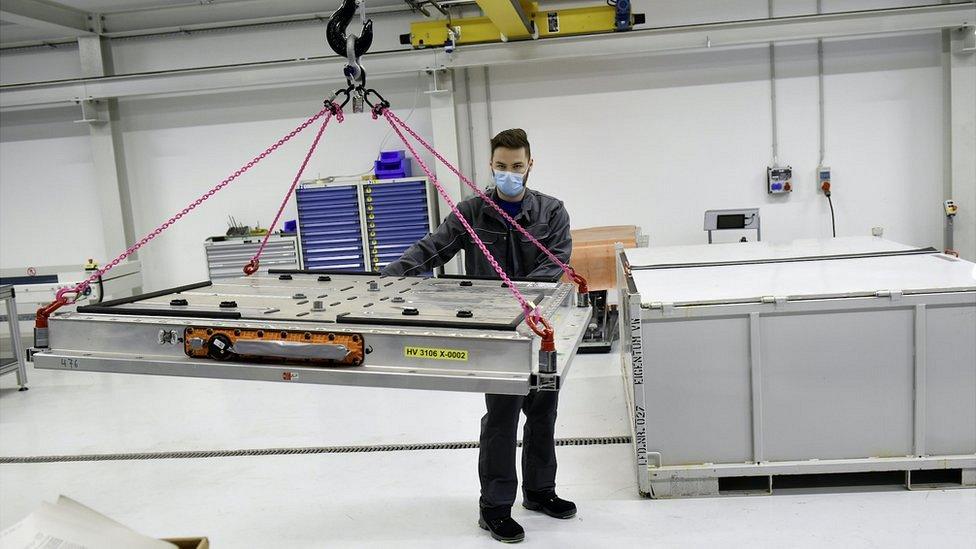

Volkswagen has a pilot recycling plant in Salzgitter, Germany

Volkswagen is doing the same, but has also recently opened its first recycling plant, in Salzgitter, Germany, and plans to recycle up to 3,600 battery systems per year during the pilot phase.

"As a result of the recycling process, many different materials are recovered. As a first step we focus on cathode metals like cobalt, nickel, lithium and manganese," says Thomas Tiedje, head of planning for recycling at Volkswagen Group Components.

"Dismantled parts of the battery systems such as aluminium and copper are given into established recycling streams."

Renault, meanwhile, is now recycling all its electric car batteries - although as things stand, that only amounts to a couple of hundred a year. It does this through a consortium with French waste management company Veolia and Belgian chemical firm Solvay.

"We are aiming at being able to address 25% of the recycling market. We want to maintain this level of coverage, and of course this would cover by far the needs of Renault," says Jean-Philippe Hermine, Renault's VP for strategic environmental planning.

"It's a very open project - it's not to recycle only Renault batteries but all batteries, and also including production waste from the battery manufacturing plants."

Dismantling the battery into its parts is time-consuming

The issue is also receiving attention from scientific bodies such as the Faraday Institution, whose ReLiB project aims to optimise the recycling of EV batteries and make it as streamlined as possible.

"We imagine a more efficient, more cost-effective industry in future, instead of going through some of the processes that are available - and can be scaled up now - but are not terribly efficient," says Dr Anderson, who is principal investigator for the project.

Currently, for example, much of the substance of a battery is reduced during the recycling process to what is called black mass - a mixture of lithium, manganese, cobalt and nickel - which needs further, energy-intensive processing to recover the materials in a usable form.

Manually dismantling fuel cells allows for more of these materials to be efficiently recovered, but brings problems of its own.

Automating battery recycling will make it more economical and safer, says Birmingham University's Gavin Harper

"In some markets, such as China, health and safety regulation and environmental regulation is much more lax, and working conditions wouldn't be accepted in a Western context," says Gavin Harper, Faraday Institution research fellow.

"Also, because labour is more expensive, the whole economics of it make it difficult to make it a good proposition in the UK."

The answer, he says, is automation and robotics: "If you can automate that, we can pull some of the danger out of it and make it more economically efficient."

And there are indeed powerful economic arguments for improving the recyclability of EV batteries - not least, the fact that many of the elements used are hard to come by in Europe and the UK.

"You've got the waste management problem on the one hand, but then on the flip side of that you've also got a great opportunity because obviously the UK doesn't have indigenous supplies of many factory materials," says Dr Harper.

"There's a bit of lithium in Cornwall, but by and large we've got challenges in terms of sourcing the factory materials that we need."

From a manufacturer's point of view, therefore, recycling old batteries is the safest way to ensure a ready supply of new ones.

"We need to secure - as a manufacturer, as Europeans - the sourcing of these materials that are strategic for mobility and for the industry," says Mr Hermine.

"We don't have access to these materials outside of this recycling field - the end-of-life battery is the urban mining of Europe."