The little tech firm gunning for an airspeed record

- Published

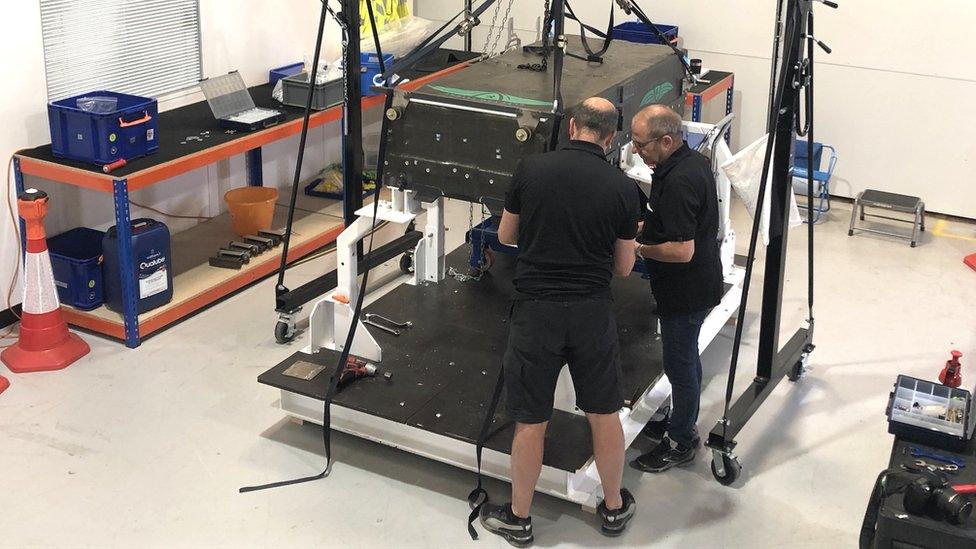

The E-NXT has been under development for three years

Gloucestershire Airport is a pretty quiet place, mainly serving flight training schools and private aircraft.

But among the hangars and industrial units attached to the airfield, a very special aircraft has been under construction.

The Electric NXT or E-NXT is a single-seater aircraft developed by Electroflight and the aerospace giant Rolls-Royce that they hope will soon break the world speed record for an electric aircraft by travelling at more than 480km/h (300mph). The current record stands at 342km/h (213mph), external.

For Rolls-Royce the project (which it calls Accel) is part of a broader effort to develop technology that will reduce the environmental impact of flying.

It has been working with Electroflight on E-NXT for three years, spending £6m ($8.3m; €7m) to develop the cutting edge technology needed for the record run.

Many of the 20-strong engineering team working at Electroflight's hangar have backgrounds in motor racing, and managing director Stjohn Youngman comes from the sports car industry. For him, the connection with performance cars was crucial when Electroflight approached Rolls-Royce with its idea three years ago.

"In aerospace, electrification was a brand new technology - and it's quite daunting to take that on from a traditional background.

"But if you look at the UK as a whole and our engineering capability, we're world leaders in niche automotive, especially motorsport electrification - Formula E is pretty much engineered in the UK.

"So we've got this talent pool of people that are in automotive, but wouldn't necessarily consider job opportunities in the aerospace business. We offered a conduit, to get that talent into the building."

Stjohn Youngman is bringing knowledge from the automotive industry into aerospace

However, building battery-driven aircraft is an even bigger challenge than building battery-driven cars. For a start, an aircraft has to drag its batteries into the sky and ideally keep them there.

The battery system for E-NXT weighs 300kg - that's almost half the entire weight of the aircraft.

So most of Electroflight's work has gone into developing the battery system, all the time thinking about the trade-off between weight and power.

"There are no free lunches in engineering - you can't trick physics," Mr Youngman jokes.

Achieving a record-breaking speed will put the battery system under serious strain.

While many sports cars can develop more than 500 horsepower, they only need that power for short bursts.

Electroflight's aircraft will need to sustain almost all of that power output for its entire record-breaking run - around eight minutes.

Even at cruising speed the batteries will be operating at 60% of their maximum output.

To help keep the weight down they have housed the entire battery system in a tough carbon fibre shell.

It is so strong that the motor, supplied by another partner, Oxford-based Yasa, is fixed directly to the battery case.

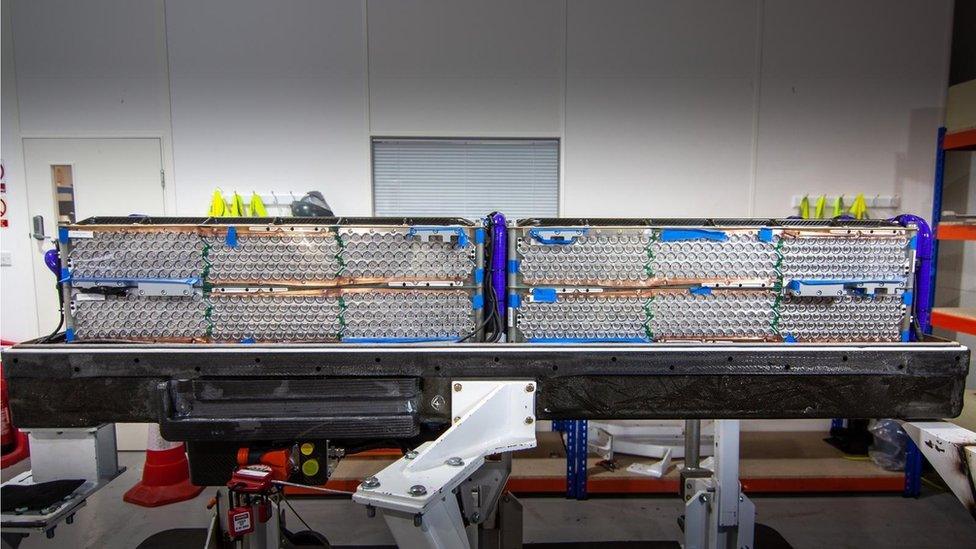

The battery pack houses three independent battery systems

Inside are actually three independent battery packs - a safety feature which means the aircraft will still have power even if one or two of the packs fail.

There are 6,400 individual cells divided among those those three packs - each cell a little larger than the AA batteries you might have at home - the same type that are used in electric cars today.

The whole battery system is cooled by an elaborate system of pipework which runs a mixture of water and glycol around the batteries to keep temperatures down.

While the record attempt is the focus right now, Electroflight hopes that the engineering know-how that it has gathered has given it a head start in the market for batteries for aircraft.

At the moment that is not a huge business, but governments around the world are committed to making aviation greener and many electric aircraft are under development.

The battery packs are made up of thousands of individual cells

In the early days of electric aircraft it's likely that batteries will have to be replaced frequently, perhaps for recharging, and definitely when they get older and less efficient, so cost will be a big factor.

Electroflight plans to tackle this and to bring the price down by setting up a facility to mass produce them.

It will represent a change of mindset in the aerospace industry, which often operates by making relatively small numbers of high- value, high-quality parts.

"It's pretty unique, because aerospace has never had to solve this problem before. Normally the volume level of aerospace components is comparatively quite low," says Mr Youngman.

"The only way to do this is through highly autonomous manufacturing techniques, which is something that automotive has already done."

Electroflight has other innovations in mind, including switching from the cylindrical cells to pouch-like cells, which have an advanced internal chemistry, making them more energy-dense whilst retaining good power output.

Pouches might take over from cylindrical cells

At the moment, it is not clear what future aircraft will look like, or how they will be powered - and batteries are unlikely to be the only answer.

"Batteries are great for releasing energy but not so great for storing it, so we can use them on their own for short flights, and get rid of all the complication and mess of liquid fuel," says Steve Wright an avionics expert at the University of the West of England.

"For longer flights we are going to need hydrogen or alternative green fuels for a long time yet.

"The solution is a typical case of what I think of as typical 21st Century tech: a mash-up of many different kinds of machine, carefully orchestrated by computers that engineers could only dream of 50 years ago," Dr Wright says.

Meanwhile back at Gloucester Airport the staff at Electroflight are getting excited.

Kristine Cirse is a technician who works on the battery systems.

"It is amazing that I'm building batteries for this plane... I want to see this plane in the sky and reach the record."

Follow Technology of Business editor Ben Morris on Twitter, external.