What is solarpunk and can it help save the planet?

- Published

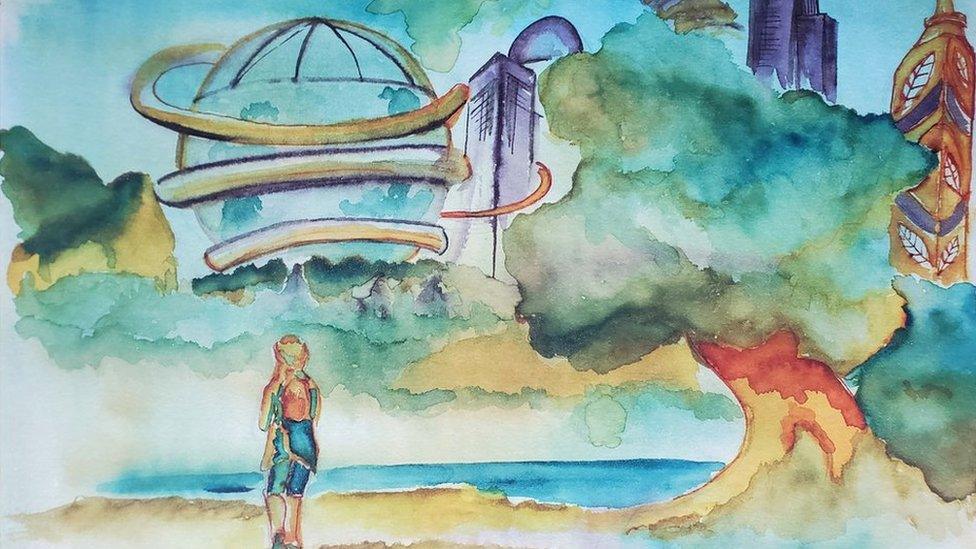

The solarpunk aesthetic depicts nature and technology in harmony

Lush green communities with roof top gardens, floating villages, transport fuelled by clean energy and hope-filled sci-fi tales. Imagine a world in which existing technologies are deployed for the greater good of both people and the planet.

It's called solarpunk. The term, coined in 2008, refers to an art movement which broadly envisions how the future might look if we lived in harmony with nature in a sustainable and egalitarian world.

"Solarpunk is really the only solution to the existential corner of climate disaster we have backed ourselves into as a species," says Michelle Tulumello, a solarpunk art teacher in New York state.

"If we wish to survive and keep some of the things we care about on the earth with us, it involves a necessary fundamental alteration in our world view where we change our outlook completely from competitive to cooperative."

But what impact is this burgeoning, utopian, movement having on the technology industry? Are they inspired? Are they even listening?

Renewable energy is a manifestation of the solarpunk aesthetic, says Tate Cantrell from Verne Global

Verne Global runs data centre services from a campus in Iceland, powered by 100% renewable energy.

The company's chief technology officer, Tate Cantrell says Iceland's supernatural land-scape fits perfectly with solarpunk.

"The solarpunk ethos embraces technology that disappears into the environment, and technology powered by renewable energy is a literal part of the circular economy - one that eliminates waste through the continual use of resources. This synergy makes renewable energy a very real manifestation of a solarpunk future," he says.

But not all companies that work in the green economy are aware of the movement.

Daniel Egger is chief commercial officer of Climeworks, a Swiss company which captures carbon dioxide (CO2) directly from the air using machines powered by renewable energy or energy-from-waste.

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies, are seen by many as an important way of bringing CO2 under control.

"Our goal is to inspire a billion people to remove carbon from the air," he says. "It is definitely not our target to do that alone - we need to be part of an ecosystem."

Iceland's supernatural landscape has inspired some tech entrepreneurs

Yet despite aiming to tackle climate change and galvanise the wider community, Egger says the firm doesn't have much knowledge about solarpunk. "It's not that we don't appreciate what others are thinking, but the overlay between Climeworks and solarpunk isn't big."

Perhaps the anarchic connotations of punk are off-putting for some?

"Prescribing to people that they need to be more solarpunk is much less inviting to them than encouraging people to exercise their own imaginations," says Phoebe Tickell, scientist, systems designer, social entrepreneur and co-founder of Moral Imaginations, which works with organisations including universities, local councils and communities to encourage the reimagining of a better world.

"We use imagination as the carrot on a stick because every company and corporation knows that to weather the future and be resilient they need employees who are creative, imaginative and able to flex and be resilient in a volatile, uncertain, complex, ambiguous world.

"Our hope is that they go on to create and align with solarpunk visions," she says.

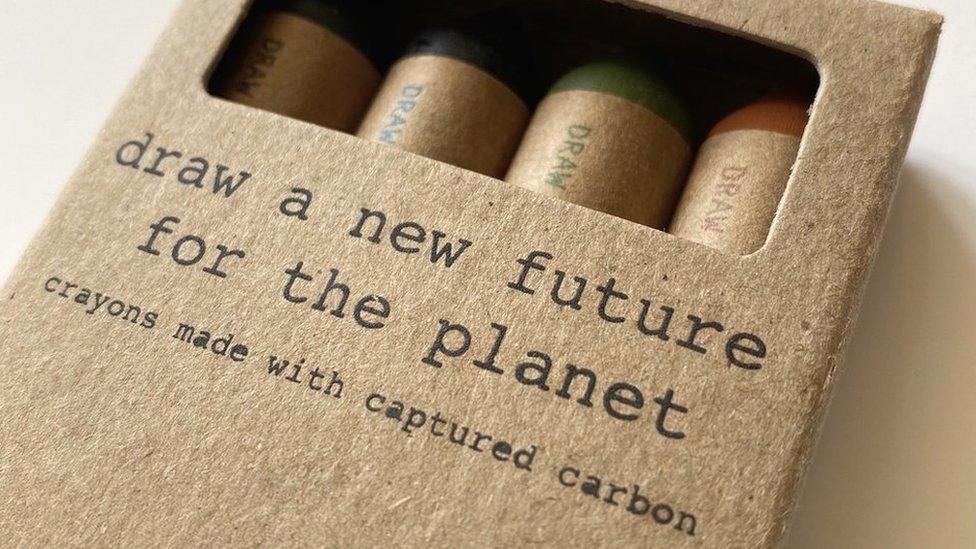

Canadian firm Carbon Upcycling Technologies (CUT) is one organisation that is harnessing solarpunk to communicate its vision. Its reactor technology allows material to be broken down and CO2 absorbed, creating enhanced concrete additives.

In 2020, CUT launched a consumer brand, Expedition Air, selling products like paintings and T-shirts made from carbon-captured material. It is a move rooted in solarpunk and is based on an Artist in Residence programme.

Madison Savilow has found artists positive about materials made from captured carbon

"As soon as we started doing work with artists to demonstrate how captured carbon material can be incorporated into such a variety of products, we started to receive enquiries from companies and larger brands that want to integrate our material into their existing product lines," says Madison Savilow, venture lead, Expedition Air.

One of the main drivers of its art and consumer product offerings is to allow consumers to interact with carbon-tech materials, she says, and envision a future in which products and art are actually carbon sinks.

"We've used art and consumer products to de-risk the uptake of this novel material and start conversations with companies that have the production capacity to actually move the needle in terms of carbon reduction."

But using art and imagination to get larger firms to act isn't enough. The solarpunk ethos also advocates knowledge sharing and community-centricity - not hierarchies, profit and excessive wealth for a minority. It demands a system change. Ms Tulumello says she knows several solarpunks who work in the tech sector.

"I believe our views are gaining traction there. Small, nimble, eco-friendly high-tech startups with cooperative structures will be the kind of companies solarpunks will support. Something like a cooperative, worker-owned business model would be more likely to maintain its principles and its commitment to sustainability and carbon neutrality."

Crayons made from captured carbon

The open source ethos is at the heart of many such businesses. One example is US-based Open Source Ecology, which develops industrial machines, such as tractors, ovens or cement makers, that can be made for a fraction of commercial cost and shares its designs online for free. Its aim is to create an open source economy.

Ellie Day, a software engineer and solarpunk enthusiast, says for something to be truly solarpunk it needs to be beyond profit. "Sure, capitalism can contribute to the technology, but people need to come before profit, always. So if tech companies can help spread the ethos of solarpunk by working with those in the space without changing what it means, I'm down with that."

Solarpunk is at odds with many large tech companies, but it remains a huge and untapped opportunity for both inspiring innovation and communicating new ideas, argue its advocates.

Ms Tickell says: "The tech industry, social justice, and the environmental industry often see themselves as quite separate, and even at war with each other.

"Solarpunk is a very powerful cultural narrative that could really bring together efforts across these sectors in an aligned way."