UK economic growth slows in May

- Published

- comments

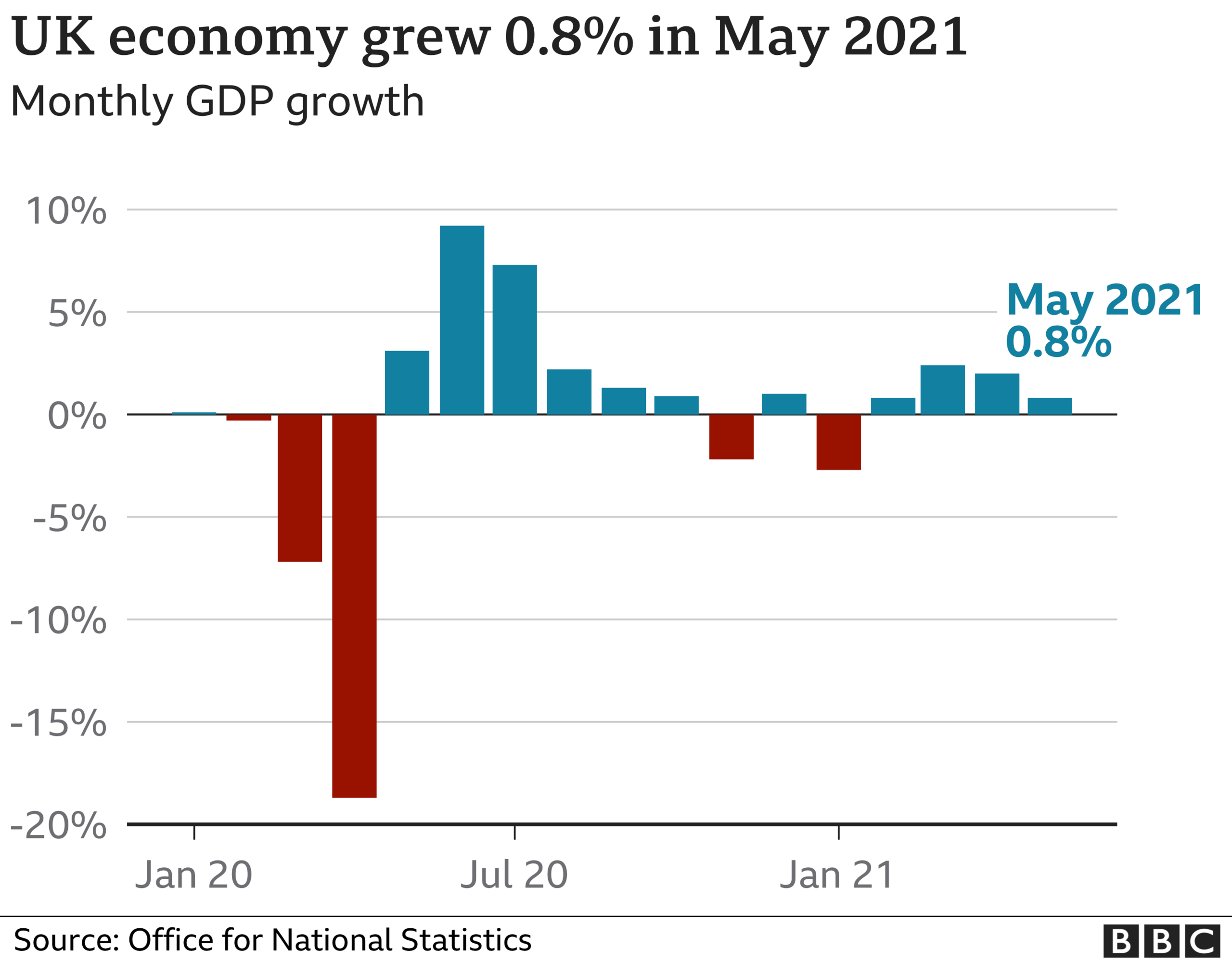

The UK's economy grew more slowly than expected in May after a rebound in the hospitality sector was offset by disruptions to car production.

The economy expanded by 0.8% in May as coronavirus restrictions eased to allow pubs and restaurants to serve indoors.

While that was the fourth consecutive month of growth, it was also a slowdown from the 2% growth seen in April.

The economy is still 3.1% below pre-pandemic levels, the Office for National Statistics said, external.

"Of course, the pace of the recovery was always going to slow as the economy climbed back towards its pre-crisis level. But we hadn't expected it to slow so much so soon," said Paul Dales, an economist with Capital Economics.

Pubs and restaurants "were responsible for the vast majority of the growth seen in May", said Jonathan Athow, ONS deputy national statistician for economic statistics

"Hotels also saw a marked recovery as restrictions lifted," he added.

Accommodation and food services grew by a massive 37.1% in May, with the overall services sector growing 0.9%.

But UK carmakers struggled with a shortage of microchips, with the manufacture of transport equipment falling by 16.5%.

Construction firms were hit by very wet weather in May as firms lost working days, although the ONS said the sector remained 0.3% above February 2020's pre-pandemic level.

British Chambers of Commerce head of economics Suren Thiru said: "While the latest figures confirm the rebound in economic activity continued into May, the sharp slowdown in growth suggests that the recovery is losing a little steam as the temporary boost, from the earlier phases of reopening, fades."

Overall, in the three months to May, economic output rose by 3.6%, helped by strong retail sales, and as pubs, restaurants and schools reopened from March.

Chancellor Rishi Sunak said: "The government is continuing to support the recovery, with the furlough scheme in place until September, and schemes like Restart helping people who have sadly lost their jobs get back into work."

Looking ahead, Emma-Lou Montgomery, associate director at Fidelity International, said: "A sporting summer may not directly cause an 'it's coming home' bounce, but the impact on consumer confidence can't be ignored.

"That being said, there are many unknowns ahead. The UK is set on its roadmap to 'freedom day' but cases are rising, challenges in the labour market persist and the initial spending boom could slow in pace."

Still weak

After shrinking at the start of the year under renewed lockdowns, the economy is meant to be surging back. On a chart, a line graph looks like the second bounce of a precipitous economic bungee jump.

In that light, today's figures are a disappointment. The consensus forecast was for growth of 1.5% in May.

Instead we got barely half that - 0.8% - with activity in construction shrinking for the second month in a row and manufacturing also down.

Some of that was down to one-off factors such as the shortage of microchips, which forced carmakers to send workers home.

But while activity in restaurants and pubs jumped as customers were allowed inside for the first time in months, it's clear that our economic bungee cord is slackening before it was expected.

The economy remains 3.1% below where it was in February last year, and no larger than it was in January 2017, making it one of the two weakest performers in the G20 group of advanced economies.

What is GDP?

In the UK, new GDP figures are produced every month, but the quarterly figures - covering three months at a time - are the most widely watched.

In a growing economy, quarterly GDP will be slightly bigger than the quarter before, a sign that people are doing more work and getting (on average) a little bit richer.

Most economists, politicians and businesses like to see GDP rising steadily.

Rising GDP means more jobs are likely to be created, and workers are more likely to get better pay rises.

If GDP is falling, then the economy is shrinking - bad news for businesses and workers. If GDP falls for two quarters in a row, that is known as a recession, which can mean pay freezes and lost jobs.

A separate statement, external from the Office for National Statistics on trade figures showed that the UK is still importing more goods from outside the EU than from the bloc following Brexit. However, the difference is narrowing.

The value of imports from non-EU countries were £20bn in May, while imports from the bloc - many of which face new barriers to cross-border trade - were £18.4bn, the ONS said.

The value of goods exported to non-EU countries - £13.7bn - was also higher than to EU countries, at £12.9bn.

- Published8 July 2021

- Published8 July 2021