Inflation rise will be temporary, says Bank governor Bailey

- Published

- comments

The recent surge in consumer prices will be a temporary phenomenon as the UK emerges from the pandemic, the Bank of England's governor has insisted.

Andrew Bailey told the BBC the jump in inflation was understandable given the "bumpy" economic recovery.

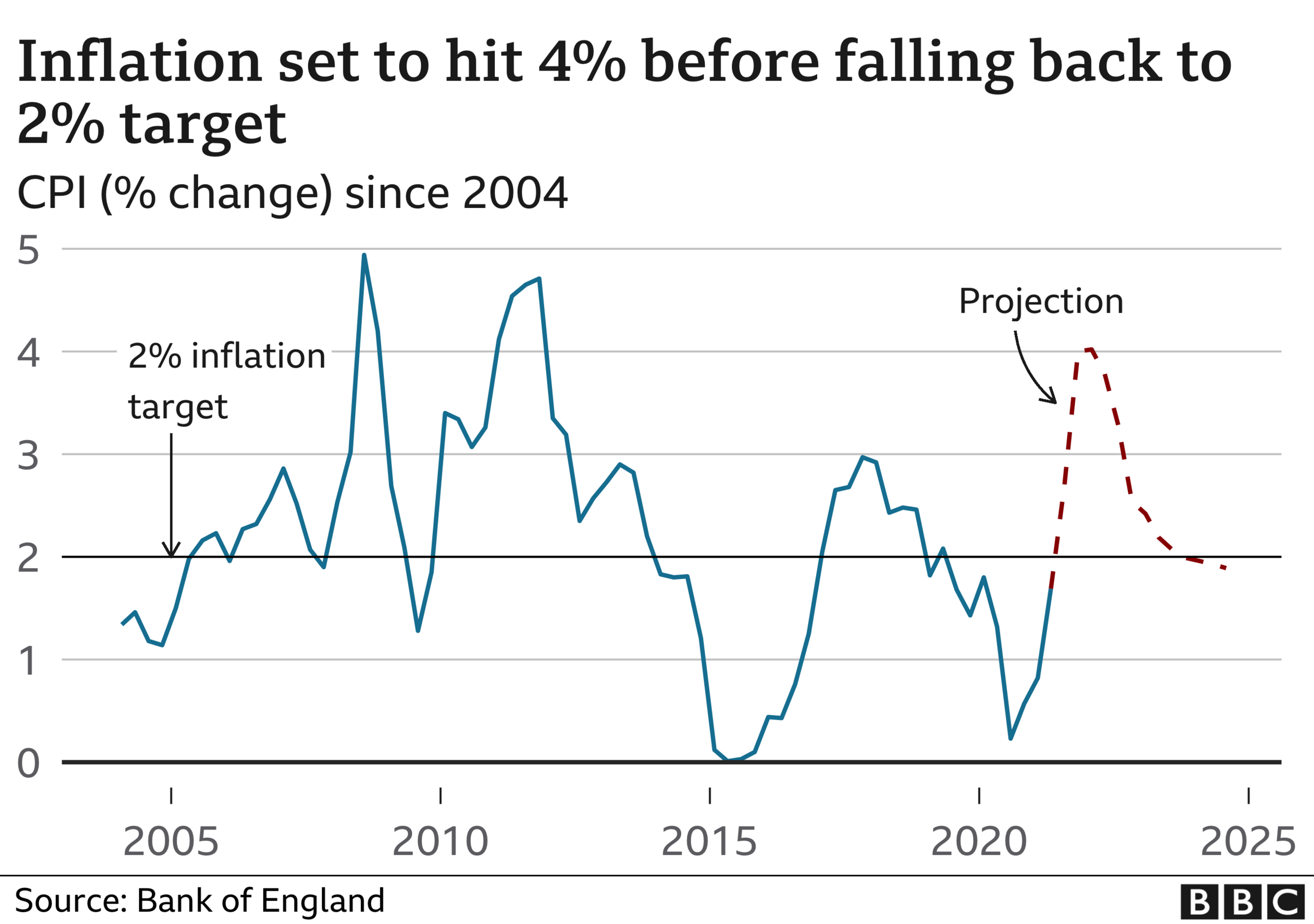

On Thursday, the Bank warned inflation will hit 4% this year, higher than previously forecast and double the 2% rate it aims for.

But policymakers decided to leave interest rates unchanged at 0.1%.

The Consumer Prices Index hit its highest for almost three years in June, at 2.5%, as food and energy costs rose.

Rate-setters on the Bank's Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) have diverged over whether rising prices fuelled by the economic recovery are temporary and when they might start to fall.

However, the committee, currently made up of eight members, not the usual nine, voted unanimously in favour of holding rates at their record low.

Mr Bailey said the rapid recovery in demand for some goods was outstripping supply, contributing to price increases, but many of the inflation drivers are "temporary".

But he added: "I want to emphasise that we don't take this [inflation rise] lightly by any means. We at the Bank of England are very focussed on inflation. But we do expect it to come back to target."

Some economists argue the Bank should rein in its economic stimulus programme - quantitative easing - but there was also no change on Thursday.

The central bank will keep up its £875bn QE following a seven to one vote in favour. Michael Saunders was the one vote against. He argued that the government bond purchases should be cut from £875bn to £830bn.

The Bank's former chief economist Andy Haldane called for a £50bn cut in QE before he left the committee after its June meeting.

Despite rising prices, the MPC concluded that it would start to fall back to the target rate of 2%.

"The Committee's central expectation is that current elevated global and domestic cost pressures will prove transitory," the Bank said in a statement.

But it added: "Nonetheless, the economy is projected to experience a more pronounced period of above-target inflation in the near term than expected in the May Report."

Separately, the Bank's latest economic growth outlook published on Thursday forecast a gross domestic product (GDP) rebound of 7.25% in 2021.

Although this is unchanged from the previous estimate of 7.25% in May, it is still the fastest growth rate for 70 years.

However, the Bank now expects the economy to then grow by 6% in 2022, compared with a previous 5.75% forecast.

Mr Bailey said he was very confident about the economic recovery. "We were criticised a year a go for being over-optimistic about the bounce-back," he said. "But the element that has come out much better than anybody forecast is unemployment."

With more than 70% of adults in Britain now fully vaccinated against COVID-19 and most social-distancing rules lifted, Britain's economy has recovered strongly since its 10% crash in 2020.

A resounding headache is not just a common symptom for those suffering from coronavirus but for those who have to deal with the economic fallout.

Inflation's usually the last thing central bankers worry about after a recession - particularly one that's the deepest since the Great Frost of 1709.

But this isn't a typical crisis. The Bank of England is bracing for inflation, to hit 4% by year-end, twice its target. However activity and employment have yet to reach pre-pandemic levels, the path of recovery uncertain once furlough ceases and given the risk of renewed restrictions.

How to balance those? The Bank is betting on the spike in inflation being transitory, reflected in the main bottlenecks in supply chains and the like as the economy adjusts.

So it's opted for a wait-and-see approach rather than risk undermining the recovery, leaving not just rates but its asset buying programme, QE, alone.

Economists think the first rate hike may still be at least a year off.

The Bank may well be right but if not, there could be a steep price for inaction. Interest rates changes typically take anything up to two years to impact prices. Leave it too late, and they may have to rise further and faster than otherwise - a fresh headache, this time for borrowers.

Related topics

- Published4 August 2021

- Published27 July 2021

- Published22 July 2021