Why phone scams are so difficult to tackle

- Published

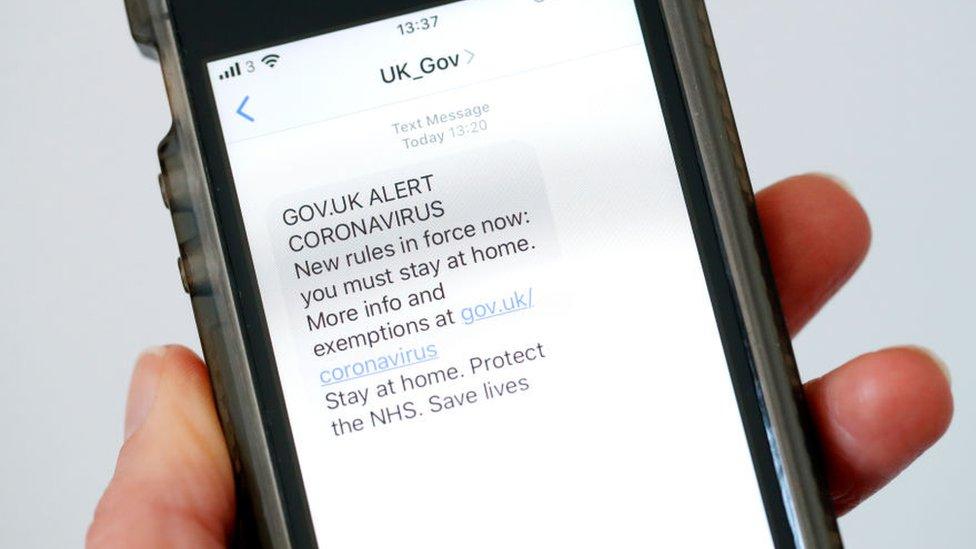

Phone fraud has soared during the pandemic

Many of us now refuse to answer telephone calls from an unknown number, for fear that it could be a scam.

And we dread receiving a text message, purportedly from our bank or a delivery firm, again due to concerns that it might be from fraudsters.

A recent report suggests that we are right to be cautious. In the 12 months to March 2021, phone call and text message fraud across England, Wales and Northern Ireland was up 83% from the previous year, according to consumer group Which?, external.

Which? analysed data from Action Fraud, the UK's national reporting centre for fraud and cyber crime, and says this was the biggest rise across all types of fraudulent attacks.

It adds that the jump was fuelled by more people getting things delivered during the pandemic, which led to a corresponding huge rise in fake parcel delivery text notifications.

The rise in delivery text message fraud has soared as more of us have bought online

In these "smishing" attacks, fraudsters send a person a message, seemingly from a legitimate number, to claim that a small payment is needed before a package can be delivered. Then when you click on the link they try to steal your banking details.

But how exactly are the fraudsters able to do this, and why is it so difficult for telecoms firms and authorities to tackle the problem?

Matthew Gribben, a cyber security expert, says that criminals are able to make it look like their phone call or text is coming from the real telephone number of a bank or delivery firm, due to continuing vulnerabilities in the UK (and other countries') telephone network systems.

"There's no way for the current UK phone network to guarantee 100% that the presentation number it is being told is the actual originating number - it has to take your word for it," says Mr Gribben, who is a former consultant to GCHQ, the UK government intelligence agency.

The core of the problem is a telephone identification protocol called SS7, which dates back to 1975. It is a little complicated, but bear with us.

SS7 tells the telephone network what number a user is calling or texting from, known as the "presentation number". This is crucial so that calls can be connected from one to another. The problem is that fraudsters can steal a presentation number, and then link it to their own number.

The issue affects both landlines and mobile phones, with SS7 still central to the 2G and 3G parts of mobile phone networks that continue to carry our voice calls and text messages - even if you have a 5G-enabled handset.

One theory is that the vulnerabilities of SS7 cannot be fixed because the telecoms firms need to give national security agencies access to their networks, but Mr Gribben says GCHQ (Britain's intelligence agency) can monitor communications without using SS7 loopholes.

The problem, he says, is that SS7 is still used in telecoms networks globally. And it needs to be replaced rather than patched up.

Text messages, including this legitimate one and many two-factor authentication messages, are sent using old technology

"SS7 was developed assuming there would always be legitimate activity [and] goodwill around the use of it," explains Katia Gonzalez, head of fraud prevention and security at BICS, a Brussels-based telecoms firm that connects and protects mobile phone networks.

"There's too much legacy technology [reliant upon it] that we can't move away from - we're going to have these SS7 2G/3G networks for at least another 10 years."

Jon France, head of industry security at the GSMA, the trade organisation that represents mobile network providers around the world, says that "a lot of these problems will disappear" after 5G networks have been fully rolled out. This will mean that SS7 - and 2G and 3G - can be totally replaced.

Ms Gonzalez agrees: "It took some time to understand these flaws, and how they were exploited. Now with 5G there will be security from [the centre] of it."

However, Mr Gribben cautions that even when SS7 is replaced by something "entirely brand new and sparkling, there will still be other vulnerabilities [that fraudsters can exploit]".

Experts say that when phone systems all go 5G, it will be much harder for fraudsters to hack them

The GSMA says that telecoms firms are putting "a large amount of effort and investment" into tackling scams.

For its part, BICS is using artificial intelligence systems to try to detect and block incoming fraudulent calls and texts.

Ms Gonzalez adds the only way to prevent text message scams is to enable telecoms firms to use AI to scan texts for links to fake websites before they are sent. Yet privacy regulators are unlikely to ever agree to that.

So instead BICS is calling for "greater collaboration between telecoms firms and governments, better relations between countries, and more effort from the companies on sharing information on the latest vulnerabilities".

New Tech Economy is a series exploring how technological innovation is set to shape the new emerging economic landscape.

When it comes to fraudulent telephone calls, there has been a big increase in so-called "robo-calling" - automated voice calls in recent years.

Call authentication systems do exist that can help stop them, and the UK's telecommunications regulator Ofcom says it is consulting with the telecoms industry to see what can be implemented, and how soon.

"These criminal scams are becoming more sophisticated and tackling them requires efforts from a range of bodies," says an Ofcom spokesman.

"We're working closely with the police, industry and organisations such as NCSC [the National Cyber Security Centre] - which is responsible for cyber-security standards in the UK - to help tackle the problem."

An international standards body, the US-based Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) has also developed new protocols to prevent robo-calling.

In a nod to James Bond, the system is called "Stir and Shaken". US authorities have ordered mobile operators to implement the protocols by the end of 2021, but Ofcom says UK providers can't do so until networks are sufficiently upgraded, by 2025.

BICS’ Katia Gonzalez says that SS7 is here for another decade

As phone and text scams are not going away anytime soon, Amanda Finch, chief executive of professional body, Chartered Institute of Information Security, says: "There's always more that telecoms firms could do".

"But, security is a continually moving target... basically everyone has to be vigilant," she adds.

Meanwhile, Robert Blumofe, chief technology officer of cloud security firm Akamai, says: "I don't think there's a world anytime soon where we can train people not to be fooled, so the solution has to include a way to block the response the text messages are trying to elicit."