Why workers face the bill for care revolution

- Published

- comments

In the next 24 hours, three hugely important decisions will be made which will have consequences for how we live in older age, and who pays for the increase in any necessary care.

These decisions have been repeatedly delayed. Put bluntly, the British political system has lacked the capacity to make tough long-term decisions in this area. The inadequacies of the care system, partly a result of decades of political short-termism, were then cruelly exposed by the pandemic.

So, something around £10bn a year has been found to make the care system fit for purpose. Firstly, to increase standards, but also to allow for more people to access it for free. Lastly, there will be a cap on the overall costs an individual will pay for care.

This is the state stepping in to help individuals plan for something that it is currently not possible to plan for - how much should you save to finance for your own care?

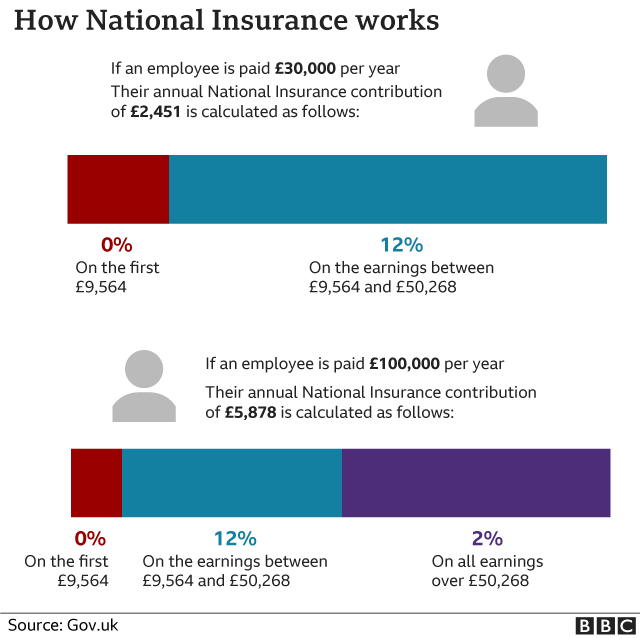

This will be paid for by a rise in National Insurance, breaking the government's "tax guarantee" manifesto commitment "not to raise the rates of income tax, National Insurance or VAT".

The government looked at other sources of income, but ultimately, only these three big taxes offer the capacity to raise the significant sums needed.

VAT would be a regressive rise, affecting the poor more. Income tax would have to go up by 2p in the pound and is not fully in the UK Government's control because of devolution.

National Insurance is viewed as the best way to raise significant sums of money as it also involves a considerable contribution from businesses.

It is also how the then chancellor Gordon Brown did it in 2003, and also the way chosen by similar nations, such as Germany and Japan.

National Insurance is also the least unpopular tax to rise.

National Insurance is, however, a tax on the working hours of those under the age of 66. It avoids property income, dividends and capital gains.

And while, broadly speaking, higher earners pay more the very wealthiest will not contribute on large swathes of their income.

Successive Conservative election campaigns have previously described a rise such as this as a "jobs tax" that will cost tens of thousands of roles.

If the government does announce a rise, it will create a generational debate about the whole package.

The first beneficiaries of it will be those in need of care, but ultimately it will be their descendants who inherit bigger estates after the government pays care bills.

The initial answer in Whitehall is that social care spending also benefits working people. But more specifically, that these significant extra tax revenues in the first three years will go on a temporary boost to NHS spending to deal with massive post-pandemic backlogs. This clearly benefits everybody.

The bulk of the social care boost will come in the next Parliament, while - over the next three years - the tax rise will fund the post-pandemic NHS rescue.

The pandemic will also be the explanation for a suspension of the triple lock pension guarantee, which determines by how much the state pension rises based on either the Consumer Prices Index measure of inflation, increases in average earnings or 2.5% - whichever of the three is the highest.

All earnings figures are distorted by the pandemic, lockdowns and furlough scheme.

So a double lock will apply, which in practice means a 3% plus inflation rise in the state pension instead of 8% that would have followed if based on the rise in average earnings. That should save £4bn a year.

This package of measures, even in its broad contours, represents generationally significant change for a long-shirked challenge.

And Number 10 and Number 11 are making significant judgements about who should pay the price.

Related topics

- Published6 November 2022

- Published6 September 2021

- Published3 September 2021