Social care reform plans facing Tory tax backlash

- Published

- comments

Boris Johnson will unveil his long-term plans for social care and the NHS as early as Tuesday, amid rows over how to pay for multi-billion pound funding.

The PM said he had a plan to reform social care when he took power in 2019 but has yet to announce the detail.

Reports of an increase in National Insurance to cover the cost - which would break his commitment not to raise taxes - has angered Tory MPs.

The NHS in England will get an extra £5.4bn over the next six months.

The prime minister said the money would "go straight to the front line" to help "bust the Covid backlogs".

Organisations representing the NHS have warned services may have to be cut unless NHS England receives an extra £10bn in funding next year.

Meetings to discuss the social care plan for England have been taking place between the PM, Chancellor Rishi Sunak and Health Secretary Sajid Javid across the weekend, according to government sources.

But while a deal is said to be "close", Laura Kuenssberg said it "sounded like haggling was still going on" over how to solve the funding issue.

And she said a delay in reaching an agreement had "created plenty of space for a backlash before the details have even emerged".

The rumoured increase in National Insurance - which has only been raised twice in the past 20 years - has particularly angered some Conservative MPs, with one cabinet minister telling the BBC: "It is the wrong thing to do, and the wrong way to go about it".

Former minister and Tory MP Jake Berry also said it would not be a "fair and equitable way" to secure the money.

He told BBC Radio 4's Today programme the rise would disproportionately affect working people "on lower wages than many others in the country", who would end up "paying tax to support people to keep hold of their houses in other parts of the country where house prices may be much higher".

What do you think about the reported social care reform plans? Email haveyoursay@bbc.co.uk, external.

Please include a contact number if you are willing to speak to a BBC journalist. You can also contact us in the following ways:

WhatsApp: +44 7756 165803

Tweet: @BBC_HaveYourSay, external

Please read our terms & conditions and privacy policy

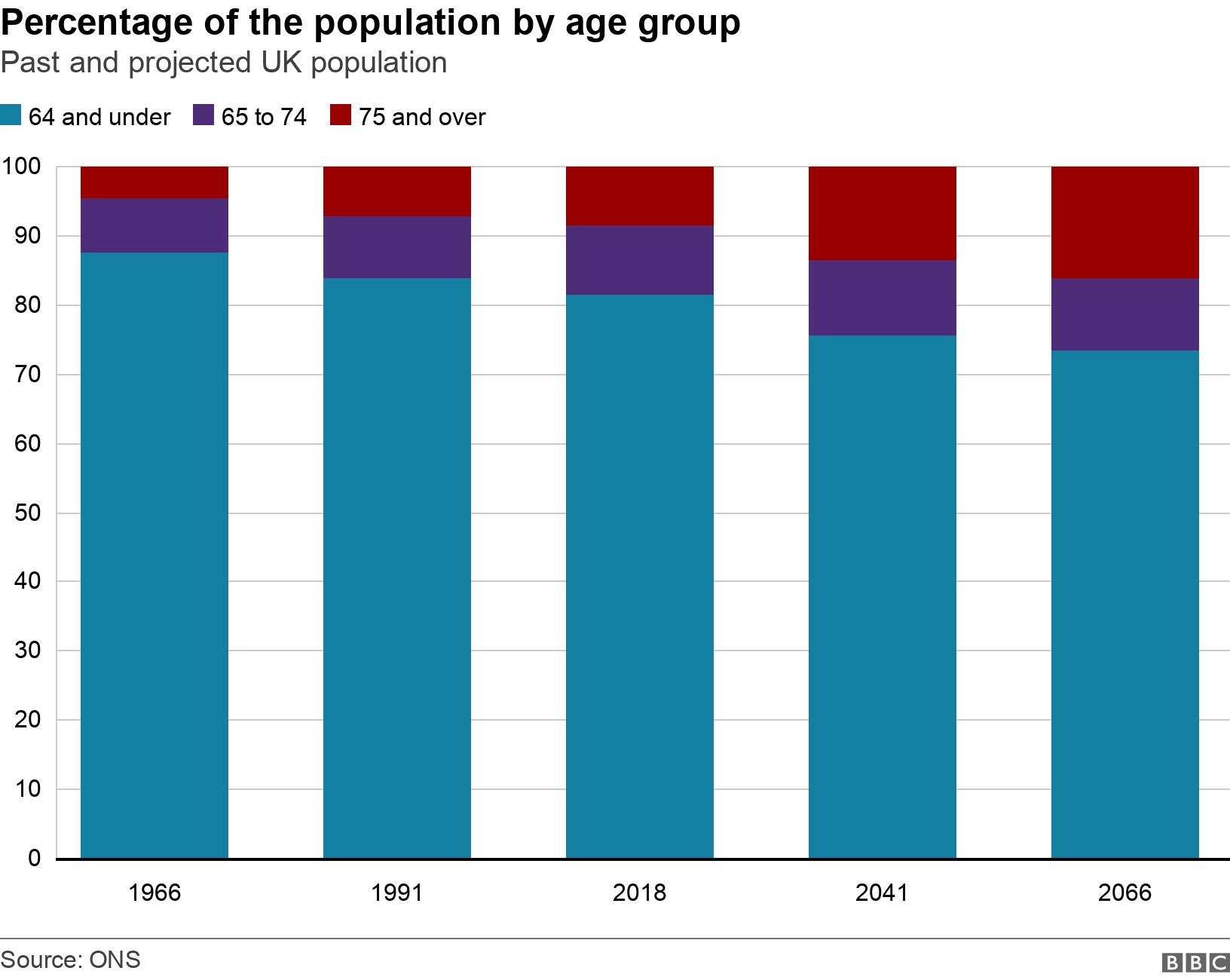

But it is widely accepted that major changes are needed to social care - which helps older and disabled people with day-to-day tasks such as washing, dressing, eating and medication - due an to ageing population and failures to address issues in the past.

Defence Minister James Heappey said too many governments had "ducked the opportunity" to fix the system, leading to the "social contract in the UK to be broken".

He told BBC Breakfast: "The social contract is that whilst you are of working age, you pay your taxes to pay for those who aren't working in anticipation that when you yourself are retired, those who are of working age at that time will do the same for you.

"That social contract has become dangerously out of balance."

Mr Heappey would not confirm if National Insurance would be part of the government's proposals, but he said any plan would have pros and cons, and it was up to MPs to "fiercely debate" them when final detail is announced.

Earlier this week, the government did not deny newspaper reports that it was considering increasing National Insurance contributions by at least 1% to improve social care and tackle the NHS backlog.

National Insurance is paid by workers until they reach the state pension age and by employers. For someone on average earnings of £29,536 a year, a 1% increase in National Insurance would cost them £199.68 annually.

Governments have only increased the tax twice since the 1990s - the Tory/Lib Dem coalition upped it in April 2011 (although it was announced by the previous Labour government) to improve public finances after the 2008 financial crash, and in 2003, Labour raised it to boost NHS spending.

The last time the Conservatives increased National Insurance was in April 1994. But on all three occasions, the figure went up by 1%.

Some Tories accept that a tax rise is needed - but say it should not be National Insurance because that could hit younger and lower income workers harder, while pensioners would not have to pay.

However, during the last election, the Conservatives made a manifesto commitment, external not to raise National Insurance, income tax or VAT.

Labour has voiced its opposition to an increase to National Insurance, with its leader, Sir Keir Starmer, ruling out his party's support.

He told the Daily Mirror newspaper, external: "We do need more investment in the NHS and social care but National Insurance, this way of doing it, simply hits low earners, it hits young people and it hits businesses.

"We don't agree that is the appropriate way to do it. Do we accept that we need more investment? Yes we do. Do we accept that NI is the right way to do it? No we don't.

"But we will look at what [the government puts] forward because after eleven years of neglect we do need a solution."

The SNP also called for the prime minister to "go back to the drawing board" over how to cover the cost.

The party's Westminster leader, Ian Blackford, tweeted: "This deeply regressive move would hammer young people, low paid workers and Scottish families by hundreds of pounds each year."

Devolved issue

The social care system is devolved across the four nations, meaning governments need to develop separate solutions.

In England, social care is generally not provided for free. Typically, only those with savings and assets worth less than £23,250 can get help from their council.

There is no overall limit on costs, meaning thousands every year end up selling their homes to pay.

Personal care, such as help with washing and dressing, is free in Scotland for those assessed by their local authority as needing it. Those in a home still have to contribute towards accommodation costs.

The SNP said the UK government at Westminster should guarantee Scottish workers would not pay for an "England-only policy".

Some care costs are capped in Wales, and home care is free for the over-75s in Northern Ireland.

For decades now there have been arguments over how we pay for the support needed as people live longer with more complex health conditions.

Scotland made the decision twenty years ago to give families more help with the costs. Wales and Northern Ireland have tweaked their systems making them slightly more generous, but in England, all plans for change have so far become mired in political arguments over how we pay the bill.

In the meantime the crisis in social care has deepened, leaving a system that is underfunded, has patchy quality, struggles to recruit enough staff and relies on the many people who fund their own care to subsidise the care of those who get council help.

Anyone with more than £23,250 pays for all their care costs, which when it comes to residential care can run into thousands of pounds a month.

This is as true for someone who bought their council house under the Tories right to buy scheme, as it is for someone who lives in a mansion.

Also about half of local authority care spending is on younger adults with disabilities and their needs are unlikely to be addressed in these plans.

The danger is that too much heat and noise over the funding mechanism will obscure meaningful discussion about what the vision should be for a care system of the future - because at its best it could help many more people live the lives they want for longer.

What are the challenges facing social care?

In 2019/20, local authorities received 1.9 million requests for support, according to the Kings Fund - up by over 100,000 in five years

While 1.4 million were from older people, 560,00 came from working age adults

In total, 839,000 people received long-term care - 548,000 older people and 290,000 working-age adults

But despite the rise in demand, the total expenditure on adult social care was only £99m more than in 2010/11, with council spending in England about 3% lower than in 2010

An ageing population also means growing demand, and Age UK estimates 1.5 million people in England don't get the help they need

The fees local authorities pay for care - in a person's own home or a care home - vary hugely

People who don't qualify for free care are often charged more, with no maximum limit on costs

There are huge staff shortages - Age UK estimates there are about 45,000 vacancies

Related topics

- Published6 November 2022

- Published5 September 2021

- Published3 September 2021

- Published28 June 2021

- Published8 February 2017

- Published4 September 2021