Government borrowing falls in September

- Published

- comments

Government borrowing fell in September compared with a year earlier as the economy continued to recover from coronavirus lockdowns.

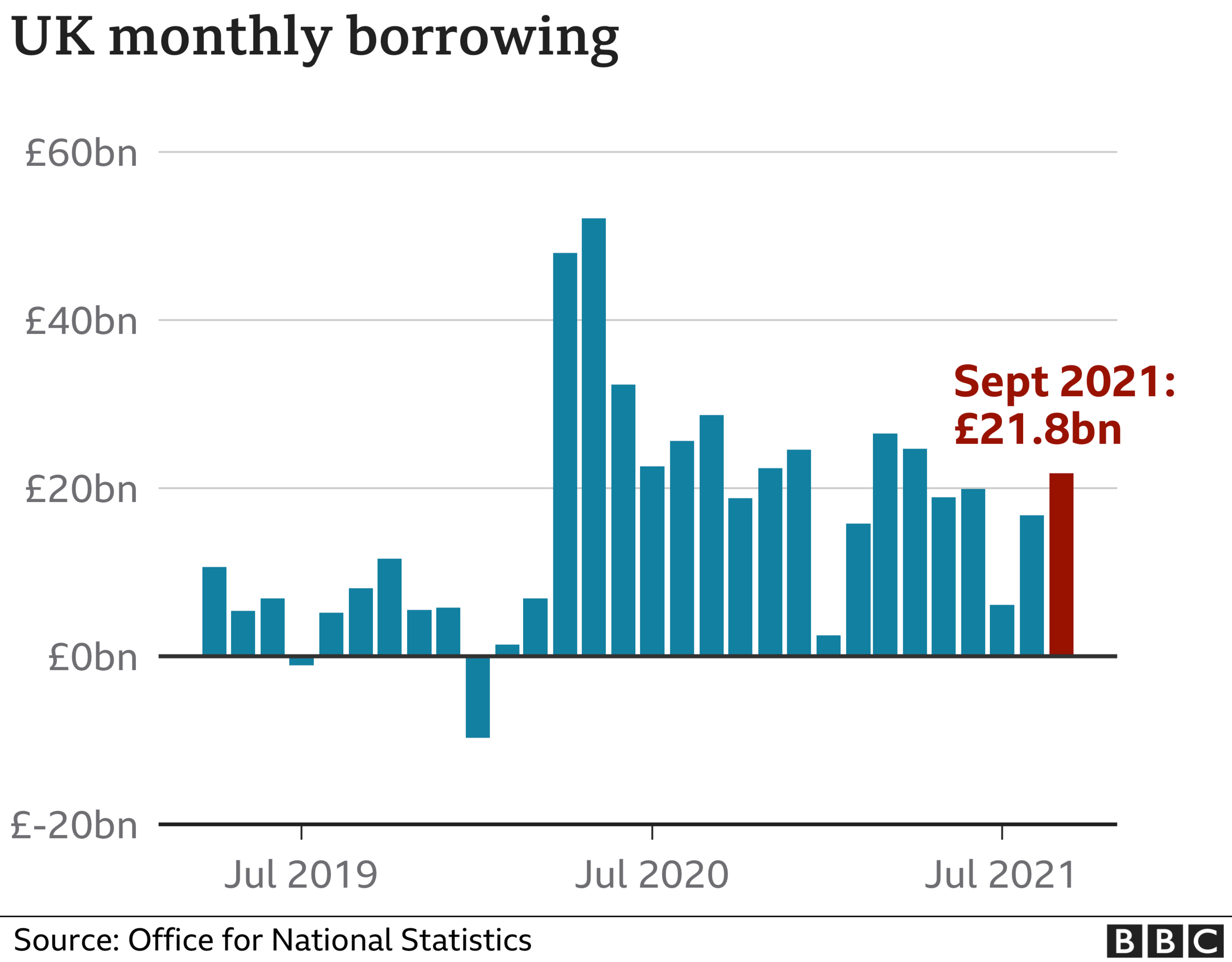

Borrowing - the difference between spending and tax income - stood at £21.8bn, which was £7bn less than in September 2020.

But the figure was still the second-highest for September since monthly records began in 1993.

Borrowing hit record levels during the pandemic.

The government spent billions of pounds on emergency measures to protect wages, such as the furlough scheme, which wrapped up last month.

As a result, government debt has been pushed up to more than £2.2 trillion at the end of September this year - about 95.5% of the UK's gross domestic product (GDP), and the highest level recorded since the early 1960s.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS), external estimates that the government has borrowed a total of £108.1bn so far in the current financial year (April to September), although this is £101.2bn less than in the same period last year.

As well as higher spending on Covid measures, the government has collected less in tax receipts during the pandemic, having given some badly-affected firms tax holidays from VAT, for example.

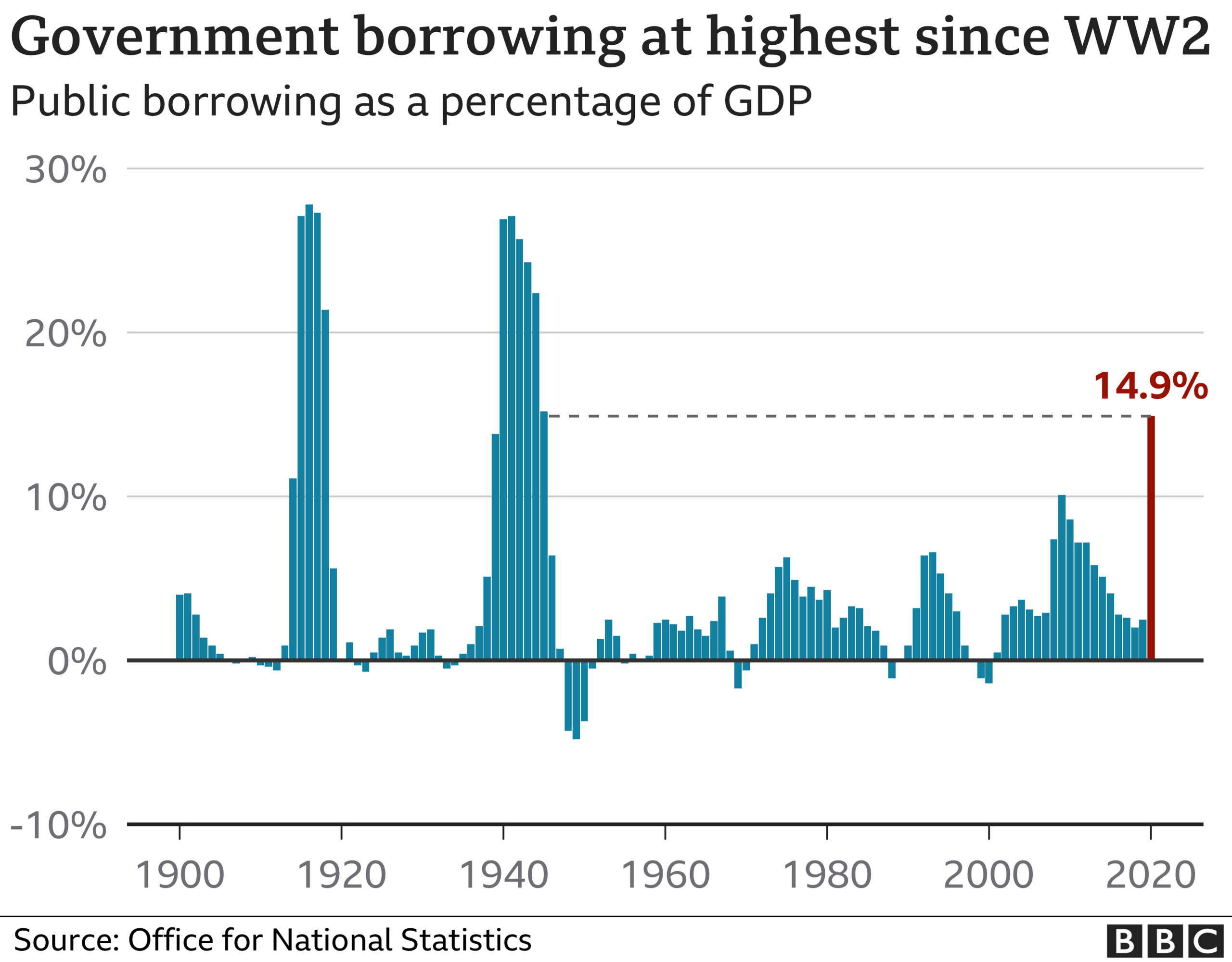

As a result of a lower income from taxes and higher spending, the ONS now estimates that in the 2020-21 financial year the government borrowed £319.9bn. That amounted to 14.9% of GDP, the highest rate seen since the end of World War Two.

Some government sources of income have started to recover more recently. In September, the amount it collected through Value Added Tax (VAT) rose by 4.5% in comparison with the same month a year earlier.

Fuel duty payments were also up by 6%, although alcohol and tobacco tax takes fell by 12.7% and 7% respectively.

'No giveaways'

Chancellor Rishi Sunak is due to deliver a new Budget and growth forecasts on 27 October, as well as new multi-year spending limits for individual government departments.

The monthly borrowing figure for September was lower than economists had expected. However, Paul Dales, chief UK economist at Capital Economics, said that while the picture had improved for the government ahead of next week's Budget, he did not expect a "major fiscal giveaway".

"Borrowing has fallen much more quickly than almost everyone expected," he said.

"That said, the rumours are that the chancellor will still keep a very tight grip on the public finances in next Wednesday's Budget to try and bring down borrowing even quicker and build a fiscal war chest to deploy ahead of the 2024 election."

In response to the latest official figures, the chancellor said that although debt levels have risen, "our recovery is well underway - with more employees on payrolls than ever before and the fastest forecast growth in the G7 this year".

"At the Budget and Spending Review next week, I will set out how we will continue to support public services, businesses and jobs while keeping our public finances fit for the future."

Andrew Bailey has warned the Bank of England "will have to act" over rising inflation

Prof David Miles, a former member of the Bank of England's Monetary Policy Committee and professor of financial economics at Imperial College, warned that there could be "a long struggle ahead" for the chancellor.

He told the BBC's Today programme: "The debt came down very rapidly after the end of the Napoleonic wars, the First World War, the Second World War.

"All those people who had been in the army and the other armed forces came back into employment, tax revenue went up, the government was spending less on armaments - that's not going to happen now, so I think it is considerably more difficult to bring down the stock of debt to GDP than it was in the aftermath of those earlier wars."

In recent years, the government has been able to borrow easily at very low interest rates, which makes its debt more affordable.

But rising inflation means that the Bank of England may increase interest rates soon, in an attempt to ensure the cost of living does not increase too quickly.

The Bank's governor, Andrew Bailey, warned on Sunday that it "will have to act" over rising inflation soon.

Although he did not give any indication as to when it might increase rates from the current record low of 0.1%, investors are expecting rates to be raised later this year or early in 2022.

What's striking in the public sector finance figures is not how big the borrowing or debt is in the financial year to date. That's the same story we've known for months: the second-highest borrowing in peacetime, second only to last year's even more extraordinary amounts.

What's newer, and more eyebrow-raising, is what the figures show about how rapidly borrowing can fall, before any spending cuts or tax rises have taken effect, simply because the economy is growing.

With expected growth this year of 7% or more, tax money is flowing into the Exchequer far faster than was anticipated at the last Budget. And much of the emergency spending required in the more severe lockdown last year no longer has to be spent because the economy has, mostly, reopened. Public sector borrowing (the amount government has to borrow to plug the gap between its income and its spending) has nearly halved, dropping by more than £100bn.

Not only that: all the borrowing accumulated over the years, also known as net debt, is also falling, down two percentage points, from 97.6% of gross domestic product in August to 95.5% in September.

Both borrowing and debt are falling, not because of any economic hairshirt the chancellor is requiring us all to wear, but because a successful vaccination programme has helped the economy to recover.

- Published11 June 2021