Inflation hits 10-year high as energy, fuel and clothing costs jump

- Published

- comments

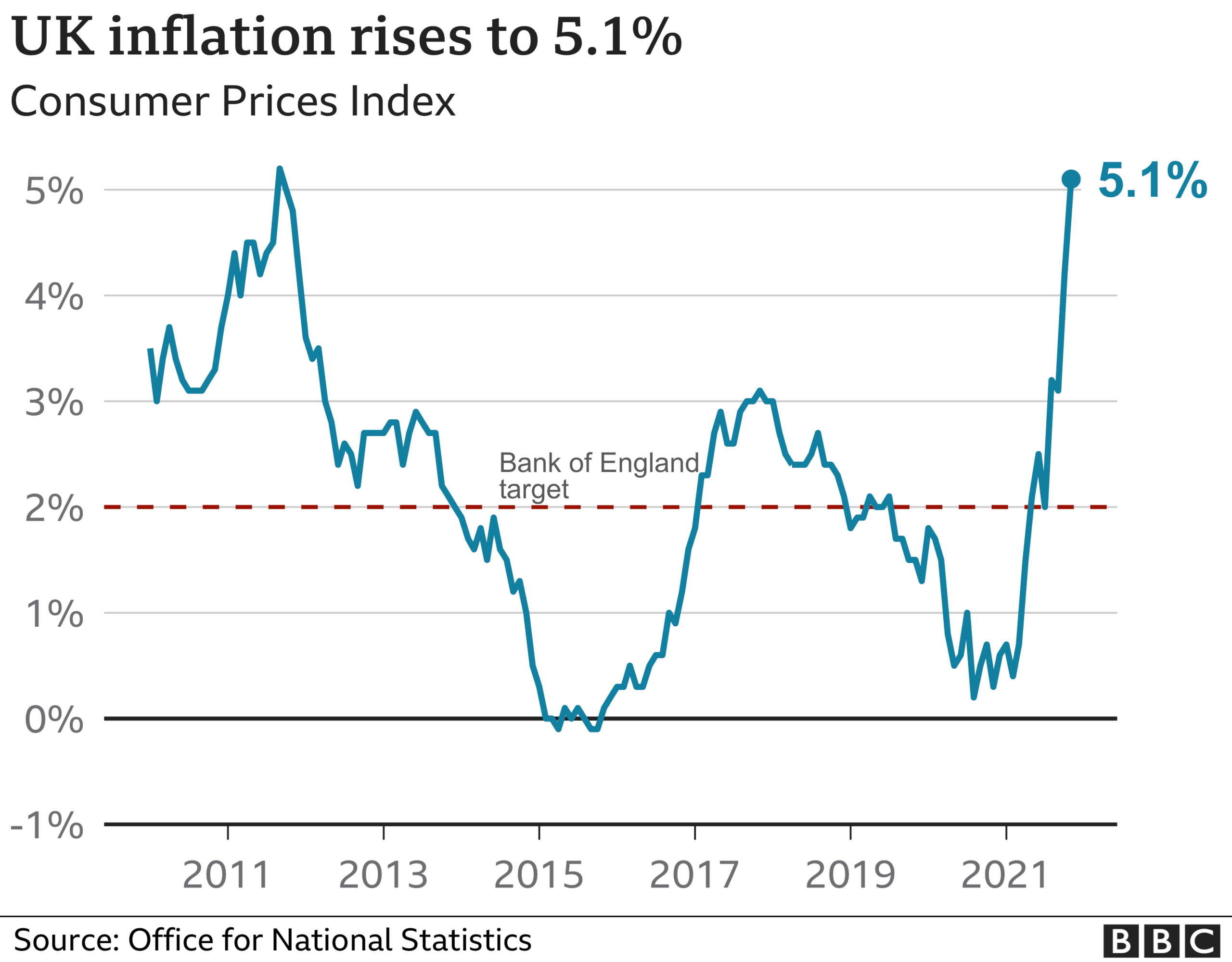

The cost of living surged by 5.1% in the 12 months to November, up from 4.2% the month before, and its highest level since September 2011.

Higher transport and energy costs drove the rise, which was above forecasts of a 4.7% increase, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) said.

Its chief economist Grant Fitzner said more expensive fuel, energy, clothing and second hand cars were big factors.

The cost of raw materials also rose significantly, he added.

What is inflation?

Inflation is the rate at which prices are rising - if the cost of a £1 jar of jam rises by 5p, then jam inflation is 5%.

It applies to services too, like having your nails done or getting your car cleaned.

You may not notice low levels of inflation from month to month, but in the long term, these price rises can have a big impact on how much you can buy with your money - sometimes referred to as the cost of living.

Why are prices rising?

Since the UK economy reopened after lockdown, companies have struggled to keep up with a surge in consumer demand.

Global supply chain problems, staff shortages and rapid demand for oil and gas have all driven up prices. The end of Covid support schemes and Brexit have also played a part.

In November, petrol prices jumped to the highest ever recorded - 145.8p a litre - while the cost of used cars jumped due to shortages of new vehicles.

A global shortage of computer chips for in new cars has led to a shortage of vehicles, leading to increased demand in the second hand car market.

Even before Wednesday's figures, the food and drink industry had warned that the soaring cost of raw materials and ingredients was having a "terrifying" impact on consumer prices.

Are consumers feeling the pinch?

Chrissy Jones from Frome has noticed energy price rises the most

Consumers are feeling the impact of price rises. Chrissy Jones, from Frome, says prices for everything from insurance to food and petrol have gone up. "We can't plan for the future," she says.

Energy bills in particular are higher. The former People's Energy customer was spending about £1,000 for both electricity and gas each year.

But when the firm went bust, she was switched onto the cheapest available tariff with British Gas, which is about double that.

"Do I fix at that price, or do I hope that the situation gets better? It's a bit of a gamble," she says.

Ms Jones is on a pension and says a lack of security around knowing what she might be spending on bills in the New Year means that she and her family are putting off plans.

A holiday in the next year was unlikely and her hopes to adopt a rescue dog were being put on hold.

"It wouldn't be fair on the dog and it wouldn't be fair on our purse," she says. "It's just incredibly worrying - you wonder where it's going to end. How much more [are prices] going to go up?"

Will inflation rise further?

That's a concern. A quadrupling of natural gas prices in the last year has still to show its full impact on domestic energy prices. Many raw material costs are still rising, which will feed into higher prices if companies cannot absorb them.

Rising inflation is not just an issue for the UK, and the government's hands are tied when it comes to dealing with what is a global problem. The latest figures for the US show prices rose 6.8% in the year to November, the highest level for almost 40 years.

Wage inflation is also a factor. The latest inflation figure is substantially above the most recent figures on average pay rises of 4.3%, meaning living standards are effectively falling.

On Wednesday, Britain's most powerful trade union, Unite, said it would act to ensure this effective pay cut was reversed.

"Current estimates suggest that costs for the typical UK family will jump by £1,700 in 2022," said Unite general secretary Sharon Graham. "Workers did not create this cost-of-living crisis so why should they pay for it?"

On Wednesday, the ONS said the retail price inflation (RPI) measure - which includes housing costs, such as council tax, and is still linked to final salary pension payments, train tickets, mobile phone tariffs, and interest on student loans - rose to 7.1%. That's up from 6%, and its highest since March 1991.

RPI rather than CPI is also used by unions for pay bargaining, and Ms Graham said members should fight for rises that matched this measure.

"Employers favour the CPI in cost calculations because it saves them money, but the truth is that this is a hidden tax on workers' wages," she said.

What are the politicians saying?

Chancellor Rishi Sunak said on Wednesday he understood the impact being felt by consumers.

He said: "We know how challenging rising inflation can be for families and households which is why we're spending £4.2bn to support living standards and provide targeted measures for the most vulnerable over the winter months.

But Labour claimed the government is not doing nearly enough to tackle the problem, especially as further inflationary pressures from rising energy costs are coming down the line.

Shadow chief secretary to the Treasury Pat McFadden said: "These figures are a stark illustration of the cost-of-living crisis facing families this Christmas.

"Instead of taking action, the government are looking the other way, blaming 'global problems' while they trap us in a high-tax, low-growth cycle."

Will interest rates rise soon?

The unexpectedly sharp jump in inflation, now more than twice the Bank of England's 2% target rate, will certainly intensify debate over a rise.

On Tuesday, the International Monetary Fund predicted inflation would reach around 5.5% early next year - its highest in 30 years - and warned the Bank not to succumb to "inaction bias".

The Bank has resisted a rate rise amid uncertainty about the impact of the Omicron variant on economic growth and people's finances.

Economist Samuel Tombs, at Pantheon Macroeconomics, said inflation is now "uncomfortably high" for the Bank, but believes rate-setters will still hold fire when they meet this week."

Yael Selfin, economist at consultancy KPMG, also thought the Bank would "adopt a wait-and-see approach at this week's meeting".

In conclusion...

Prices are rising at the fastest rate for a decade, 13 years if you use the ONS' favourite measure that includes owner-occupier housing costs.

Inflation has risen above 5% more quickly than expected by the Bank of England and others, on a path to more than 5.5% by the spring, and it is likely to stay above the Bank's 2% target for the next two years.

All of this reflects the lived experience of us all in petrol forecourts, supermarkets and department stores. The impact on living standards is material with real incomes now likely to be falling again.

It does not make an interest rate rise on Thursday a done deal, given the economic uncertainty surrounding the rapid spread of the Omicron variant of coronavirus.

The key economic uncertainty for the Bank and the Treasury is now what happens in companies and unions with how wages are set.

When combined with ongoing labour shortages, there is a lot of pressure for companies to give considerable wage rises in the new year.

While Prime Minister Boris Johnson has said he welcomes such a move, fear of a spiral of rising wages and prices is precisely what would lead to the Bank of England having to raise rates more quickly than currently expected over the next year.

Given there is little expected respite from energy prices and rising taxes, an interest rate rise on the cards in the next few months, and ongoing Omicron restrictions, the outlook for early 2022 remains challenging for consumers and businesses.

Related topics

- Published25 October 2021

- Published10 December 2021

- Published10 December 2021