MPs urge inquiry into bankers jailed for ‘rigging’ rates

- Published

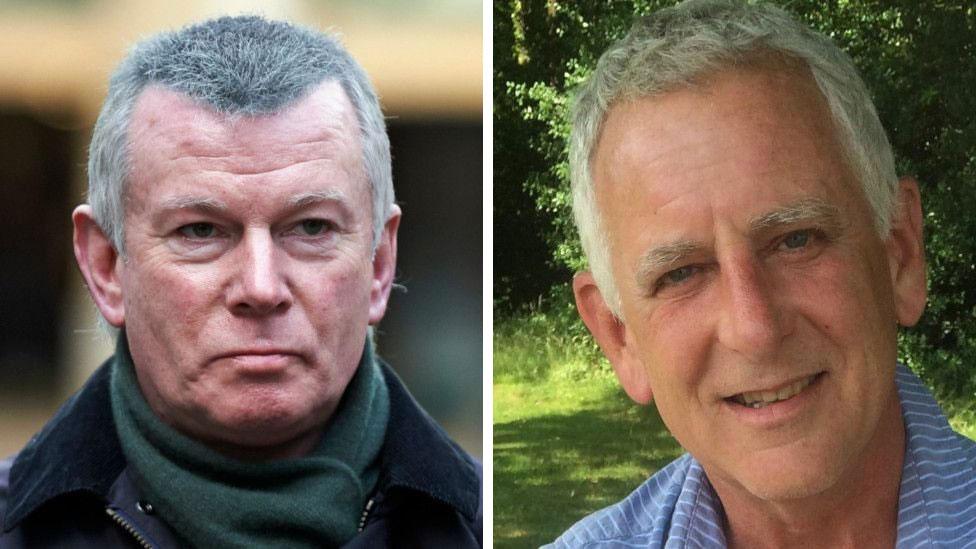

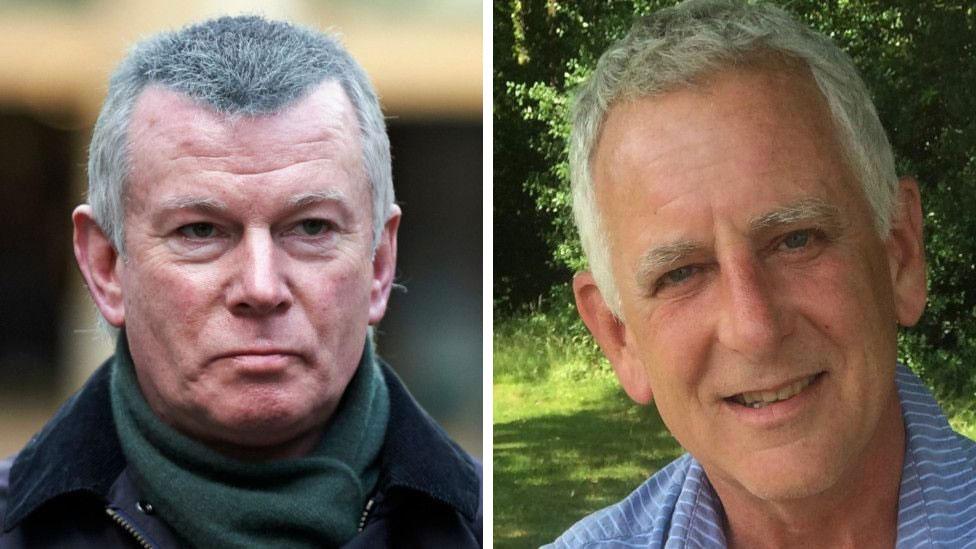

Colin Bermingham (left) and Peter Johnson

MPs have called for a fresh inquiry into the interest rate-rigging scandal which led to two bankers who blew the whistle at Barclays being jailed.

It comes after the BBC uncovered audio tapes that suggest the Bank of England and top government officials pressured Barclays to rig interest rates.

MPs on the current and former Treasury Committees are concerned that the wrong people may have been prosecuted.

The Serious Fraud office told BBC News it had run a thorough investigation.

The calls for a new inquiry follow the broadcast of a BBC Radio investigative podcast which explores traders' allegations that they are the victims of a whole series of miscarriages of justice.

It revealed that two traders jailed for rigging interest rates, Peter Johnson and Colin Bermingham, were the original whistleblowers of the scandal.

'Terrible experiences'

In the Radio 4 podcast The Lowball Tapes, the BBC revealed leaked audio recordings and documents that implicate both the Bank of England and the government in pressuring banks to rig interest rates.

The audio recordings and documents were never seen by a previous parliamentary inquiry into the scandal in 2012.

Much of the evidence was also never shown to juries in nine rate-rigging trials of traders and brokers that were held between 2015 and 2019.

A total of 38 traders were prosecuted, 24 of them in the UK. After nine criminal trials on both sides of the Atlantic, 11 were convicted.

Andrew Tyrie, who chaired the committee that investigated the scandal in 2012, told the BBC if they'd known what the BBC has since discovered they would have investigated further, changing the context in which decisions were taken to prosecute 24 traders.

"People have had their lives badly shaken up. And they've had terrible experiences from the trials," he said.

"From what I can tell the whistleblowers were, as the name suggests, trying to do the right thing. Whistleblowing is a crucial part of investigative machinery. And it's very important, it should be seen to function well. And it doesn't seem to work in this case."

The case against the convicted traders was separate to any intervention involving the Bank of England. They were alleged to have entered a conspiracy to commit fraud by asking colleagues to tweak estimates of interest rates up or down by a hundredth of a percentage point (known as a "basis point").

What does ‘rigging’ Libor or Euribor mean?

What the FTSE 100 is to share prices, Libor is to interest rates – an index that tracks the cost of borrowing cash. For most of the past 35 years, 16 banks have answered a question every morning at 11am: At what interest rate could you borrow money?

They submit their answers (e.g. RBS estimates 3.14%, Lloyds 3.13% etc) and an average is taken to get Libor, short for "London Interbank Offered Rate". To set Euribor, the process is similar but with more banks involved.

The evidence against the traders jailed for rate "rigging" consisted entirely of requests they had made to colleagues to tweak those estimated interest rates up or down, typically by one hundredth of a percentage point (known on the money markets as a "basis point").

The hope was that it might shift the Libor average marginally in the right direction to benefit the bank’s trades which went up or down linked to Libor.

In the other form of rate rigging, known as lowballing, banks pretend to be able to borrow cash much more cheaply than they really can. It is on a much larger scale.

The evidence kept from Andrew Tyrie's committee 10 years ago includes a tape, known to regulators who appeared before the committee, where Barclays trader Peter Johnson is told by his boss Mark Dearlove that the bank has had "very serious pressure from the UK government and the Bank of England about pushing our Libors lower".

However, those who gave instructions from above have never been prosecuted.

The Lowball Tapes also reveal that Mr Dearlove says he was pressured directly by then Bank of England executive director Paul Tucker earlier that month that Barclays' Libor rate should be "put down" because it was receiving attention from the government.

Evidence uncovered for the series also suggests that as it sought to manage the credit crunch and the banking crisis that followed it, the Bank of England was intervening in the Libor setting process starting in August 2007.

Emails and sworn testimony never shown to MPs nor juries suggest the Bank of England first agreed that senior bank executives should collectively raise Libor on 14 August 2007 because it was too low to reflect the interest rates where cash was changing hands. It then intervened to tell Barclays to lower its Libor submissions on 1 September 2007 following speculation about the bank's solvency.

It also shows that Barclays cash traders Peter Johnson and Colin Bermingham had sought to blow the whistle on lowballing throughout the crisis. But far from being thanked, they were separately prosecuted for a far smaller form of interest rate "rigging" which is now not regarded as a crime in the United States

Barclays' legal department, the UK regulator the Financial Services Authority and the US Department of Justice all had access to this evidence. Yet there was no mention it in the regulatory notices published at the time and no-one informed MPs about it.

The call for a fresh investigation is supported by three other former and current members of the Treasury Committee.

"It needs a new full, judge-led inquiry," said Treasury committee member and campaigner against financial corruption, Kevin Hollinrake. "You cannot have a situation where the rule-setters, the 'masters of the universe' go by one set of rules and the rest of us go by another.

"I don't care who these people are: what level of government, what level of the Bank of England, or what level of the FCA - or what level of the banks they're working in. These people have to play by the rules. So there should be an inquiry and investigation to see if they have."

Mark Garnier, who sat on the 2012 committee that was told the Bank of England hadn't put pressure on Barclays, said if he were now chairman of the Treasury committee he'd be ordering hearings to get to the truth. Teresa Pearce, a member of the same 2012 committee, said the evidence uncovered by the BBC showed the investigation needed reopening.

Paul Tucker has declined to comment in response to a BBC right of reply. Barclays didn't respond to our request for comment but former executives have denied they came under pressure from the Bank of England to lower Libor. The Bank of England has also denied that it put pressure on banks and said Libor was not regulated at the time.

The US Federal Reserve declined to comment. But in a statement from 2012, it said it had received "occasional anecdotal reports from Barclays of problems with Libor" in 2007, and shared suggestions for reform with relevant UK authorities.

Related topics

- Published1 March 2022

- Published28 January 2022

- Published22 February 2021