Will France's 'forgotten' workers get what they want?

- Published

Several decades ago there were 80 blast furnaces in the Fensch Valley with 100,000 workers

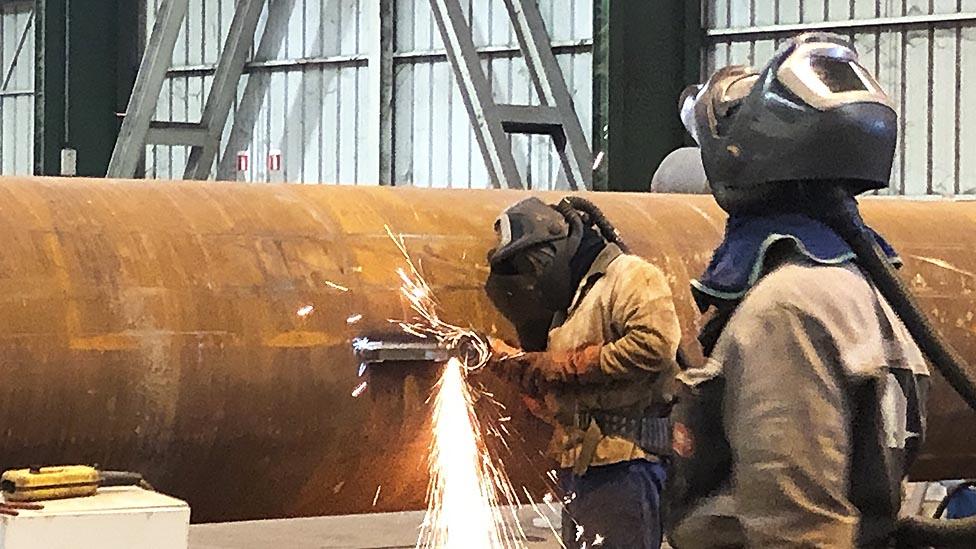

In a cavernous factory just outside Metzange in France, a group of men are building vast pipes and girders from reddish steel almost an inch thick.

Their work is illuminated by the blue glow of welding machines. Sparks fly as cutting machines are used to hone and shape the rough metal. Red dust hangs in the air and covers every surface.

The Fensch valley, in the east of the country, forms part of its industrial heartlands. The structures being made here will be transported hundreds of miles, to Paris, where they'll be used to build Le Grand Paris Express, a major new subway system for the capital.

But the director of the factory is a worried man. Stephane Costarella used to employ 50 people in the plant. Now there are only 25. He has had to cut his costs to the bone where he can - because of the rising cost of steel.

The metal being wrought here has not been produced in France. Some of it comes from across the border in Luxemburg, and some from Ukraine. But the Russian invasion has made supplies of the right kind of steel much harder to come by, pushing up prices.

Factory workers weld pipes and girders in the Fensch valley region of France

"It's a really crazy time", Mr Costarella explains. "It's really hard to get supplies. There's absolutely nothing left in storage, and the price of the steel we do get is really expensive"

On top of that, cutting and shaping inch-thick steel requires a lot of energy - and over the past few weeks his gas and electricity bills have doubled.

He says he has given up quoting prices for his clients' new projects in advance, he says, because costs are rising on a daily basis.

The current crisis is just the latest blow for an industrial region that has been in decline for decades - and the steel sector has been at the heart of that decline.

"This region has been making steel for more than a hundred years", explains Edouard Martin, a former steelworker and union activist. "In the 1950s there were 80 blast furnaces here. 100,000 workers. There were factories all along this valley - chimneys everywhere."

Blast furnaces are the giant ovens used to extract metal from iron ore, by heating it to very high temperatures while mixed with coke - a carbon-based fuel.

They have traditionally been used in the first stage of the steelmaking process. But they require manpower and are expensive to run. Across Europe, many have closed in recent years. In the UK, only a handful are left.

The last ones to close in the Moselle region were at a plant in Florange.

The factory itself remains, run by the global steel giant ArcelorMittal, a business headquartered in nearby Luxemburg. It makes steel products for the motor industry, and employs 2000 people.

The Florange plant blast furnaces have shut down for good

But the furnaces have been cold for the past decade. Their vast structures loom over the landscape. For locals they are a bitter symbol of a lost battle.

Ten years ago - as it is now France was in the throes of a presidential election campaign. The future of the Florange furnaces was a major theme. They had been closed, initially for refurbishment, but locals already knew they were unlikely to reopen.

Workers marched on the capital to make their feelings clear, Edouard Martin among them.

The future President, Francois Hollande, came to Florange and promised to protect the steel industry. But two years later, the blast furnaces closed for good.

Now, another election is looming - and the future of French industry and the jobs that go with it, are once again coming under scrutiny.

Mr Martin, who spent a period working as a socialist MEP in the European parliament, thinks action needs to be taken to safeguard the sector.

"We can't let it all go", he insists, as we stand looking at what remains of the Florange plant. The huge furnaces now bear the scars of wind and weather, and are surrounded by razor-wire fences.

"We can't rely on others for everything. Buying all our steel from China, for example.

Just look at what's happened with the war in Ukraine. We're completely dependent on Russia for our gas. It's the same for oil, it's the same for steel. We need to make things for ourselves"

Large steel plants in Germany supply much of north Europe

"I'm sure that our government, that Europe, will now have to say 'we need to preserve our industry, we need to support it'"

"But first, we need to keep our know-how. The future will be all about innovation, research and development. But in order to promote research, we need to have an industrial base."

But Olivier Dammette, of the University of Lorraine, thinks the government would be better off spending its money investing in green technology, such as waste and water management and renewable energy - rather than propping-up traditional industry.

"[Heavy] Industry only forms a relatively small part of the French economy now", he explains. "It is increasingly dominated by services, and I think that process is inevitable.

"To support industry, you'd need to inject a huge amount of public money.

"You'd save some jobs, but at a very high cost".

In an election campaign dominated by the conflict in Ukraine and the increasing cost of living, the fate of traditional industries has not been the headline-grabber it once was.

But people in the Fensch and Moselle valleys still feel their losses keenly, and remember the promises made in the past. Disillusion with mainstream politics is evident. In the last presidential election, in 2017, a third of voters did not bother to show up at the polls - a level far higher than the national average. In regional elections last year, the abstention rate was nearly 70%.

At the same time, support for the far right candidate, Marine Le Pen of the Rassemblement National (formerly the National front), has been strong.

And in an election race that appears to be getting ever closer, what voters in this region think, may yet prove significant.

Related topics

- Published21 April 2022

- Published9 April 2022

- Published29 March 2022

- Published29 March 2022