When might the inflation rate come down?

- Published

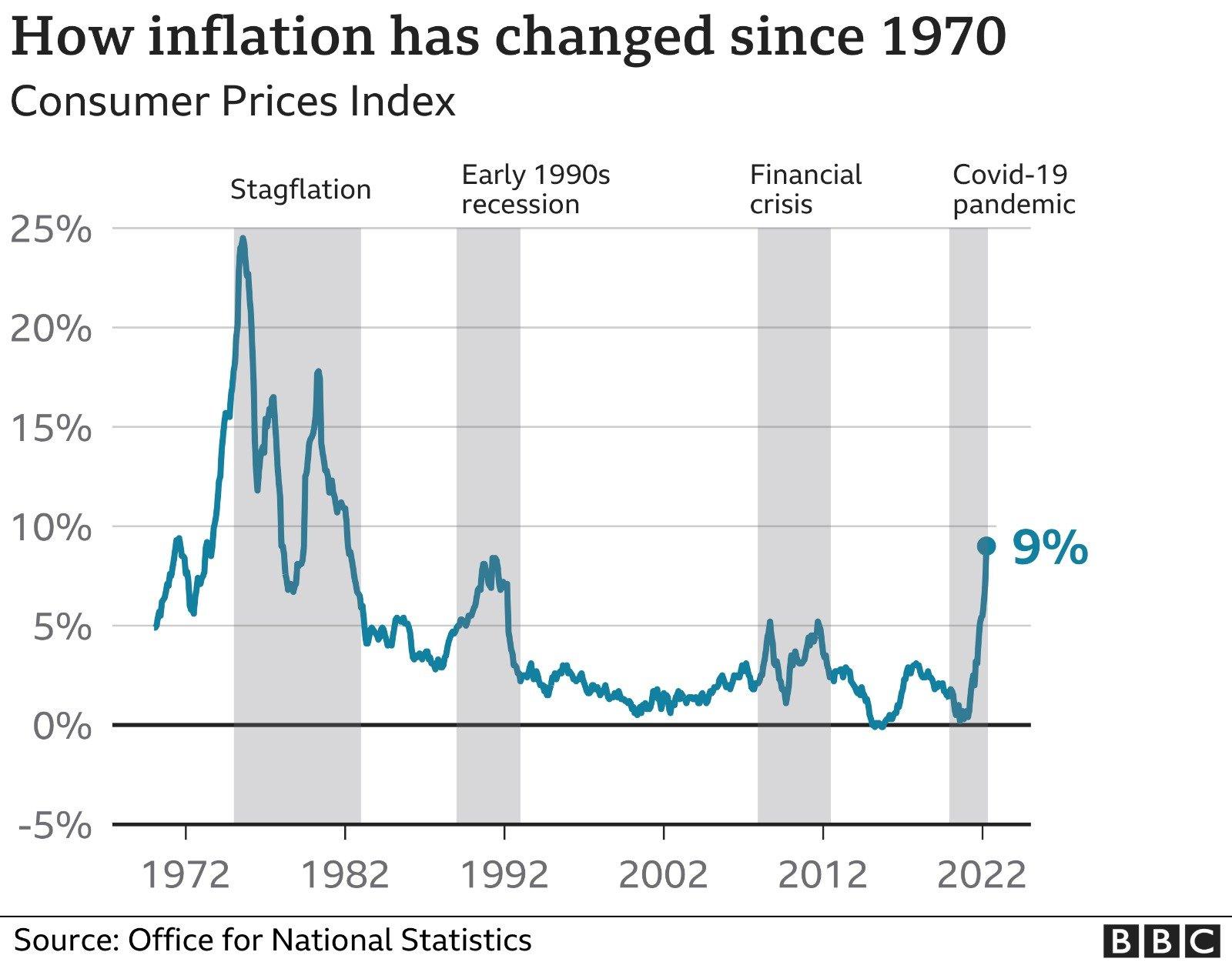

Prices in the UK have already risen by 9% over the last year - the highest rate of inflation for 40 years.

Bank of England governor Andrew Bailey has told MPs he is unable to stop inflation reaching 10%, while warning of an "apocalyptic" rise in global food prices.

But how long is inflation likely to remain this high, and what can the government do to fight back?

Why is the rate of UK inflation so high?

A 9% annual rate of inflation means - in the most basic terms - that if a loaf of bread cost £1 this time last year, it now costs £1.09. But inflation is spread unevenly across sectors in the economy - so while some prices have grown a little or stayed the same, others have rocketed upwards.

This is because inflation is being driven by the rising costs of fuel and food, and some product supply chains are more affected than others.

A 54% increase in the energy price cap has caused almost three-quarters of the jump in inflation, according to the Office for National Statistics.

Over the winter, demand for oil and gas shot up as industries in Asia returned to full capacity after the pandemic and began consuming more energy.

Russia's invasion of Ukraine put further pressure on energy prices as countries around the world scrambled to find alternatives to Russian oil and gas. Meanwhile, Ukrainian farms have been left unattended - and its wheat exports have been disrupted - putting pressure on global food supplies.

"Inflation is mostly driven by labour market shortages and supply chain disruptions," says Prof Riccardo Crescenzi, an economist at the London School of Economics.

These are made worse in the UK by significant uncertainty over trade and investment conditions, and restrictions on international labour mobility in a variety of key sectors, he says.

When will inflation come down?

The Bank of England expects the UK's energy price cap to rise again in October, which will push inflation up to 10% this autumn. Despite this, it says that the "current high rates of inflation are not likely to last".

It forecasts inflation will peak this winter - then come down to be close to 2% in about two years.

Not all economists are so sure. Historically, when inflation has risen above 9% it has taken years, not months, to recover.

Maria Demertzis, an economist at Bruegel, the Brussels-based think tank, says as long as the war in Ukraine continues, and there are concerns about where the UK will get its oil and gas from, "that's going to put a lot of pressure on prices."

To combat the effects of inflation, companies are offering higher wages to workers. But to pay for this, they often have to raise the prices of their own products and services, which fuels further inflation.

This creates what economists call an inflationary spiral.

"Inflation is likely to remain a problem in 2023 because its root causes are unlikely to change in the near future" says Prof Crescenzi.

What can be done to combat high inflation?

By raising interest rates, the Bank of England can make borrowing more expensive - encouraging people to save instead of spend. It also means some people with mortgages see their monthly payments go up.

So far, this hasn't reversed inflation, but central banks argue that without such measures, inflation would be rising faster.

The Labour Party is calling for a one-off windfall tax on oil and gas firms to help households cope with higher bills. BP's underlying profit more than doubled to £4.9bn in the first quarter of 2022, while Shell's profits almost tripled to over £7bn - both helped by the rising price of energy.

Labour say a windfall tax would raise £1.2bn but the government argues that such a tax could discourage crucial investments that would eventually bring down energy costs and so make the UK less sensitive to global oil and gas prices.

Governments can also give direct support to households by giving cash handouts, and placing caps on energy prices.

The Chancellor, Rishi Sunak, has said "we cannot protect people completely from these global challenges but are providing significant support where we can."

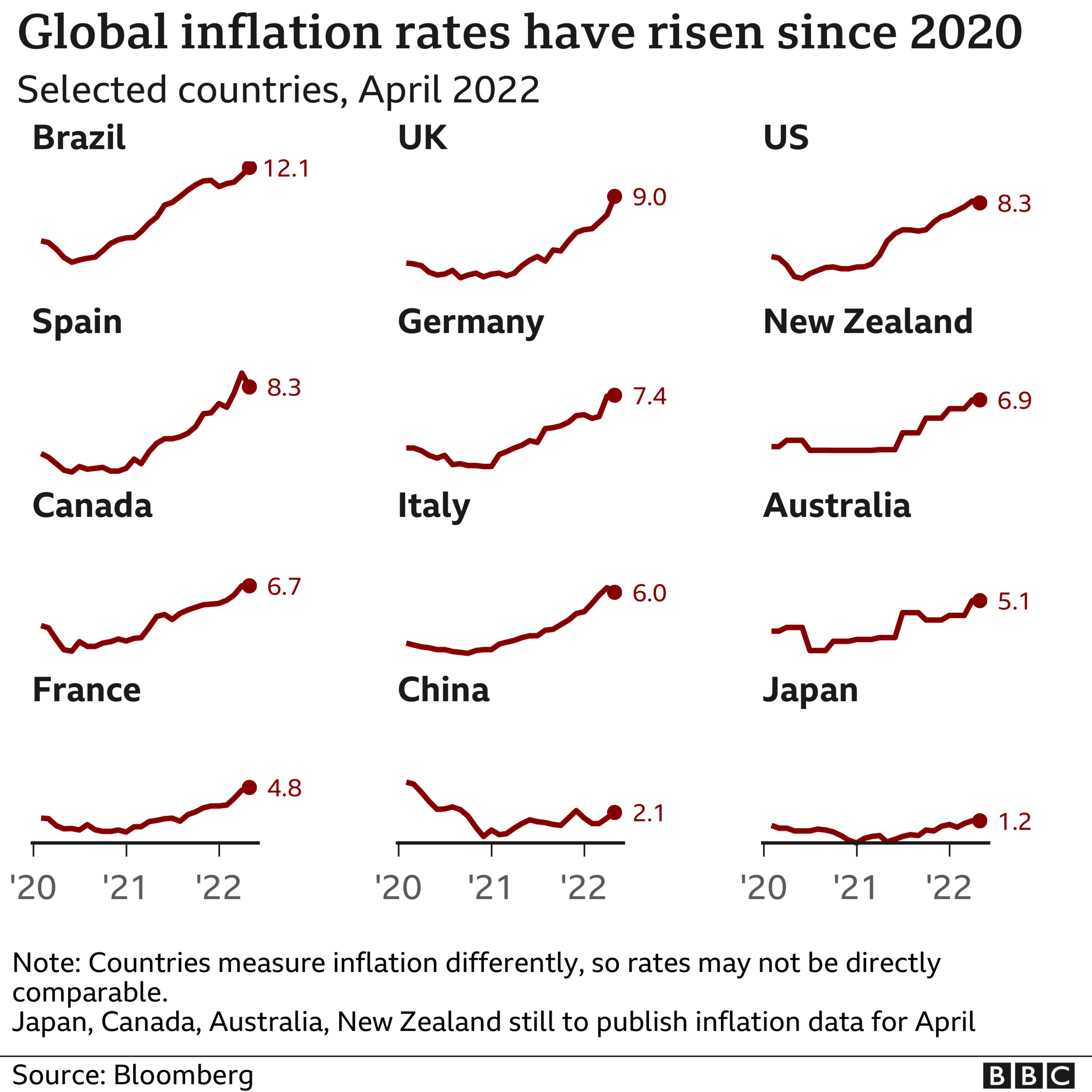

What are other countries doing about rising prices?

France

Announced a one-off €100 (£84) payment to the 5.8 million households that already receive energy vouchers, last year. Since then, it has reduced taxes on electricity and capped rises in energy bills to 4%. These measures are estimated to have cost up to €15.5bn (£13bn).

Italy

It is raising taxes on energy companies that have seen profits rise thanks to surging prices. Also announced a €14bn fuel subsidy and investment plan - allowing families to keep their fuel bills similar to 2021 levels, while also investing in renewable energy.

Germany

It has already brought in subsidies for low-income households and is now spending an extra €15bn - on fuel subsidies through cutting petrol and diesel taxes, providing people with one-off €300 pay outs, extra child support payments and public transport discounts. The total cost for these measures is about €30bn.