Finland wants to transform how we make clothes

- Published

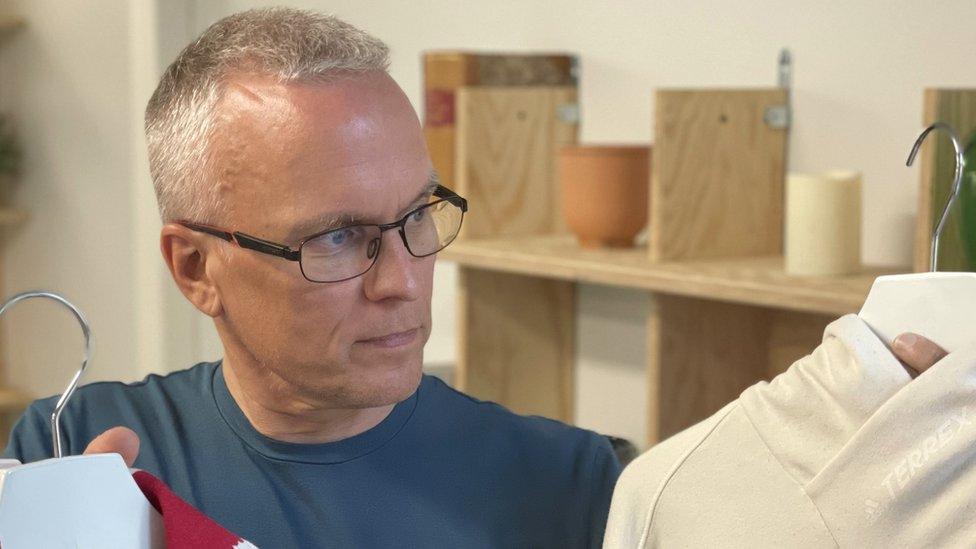

Petri Alava says his firm can make sustainable fibres on a commercial scale

Petri Alava used to wear pressed suits and leather shoes to work, managing large corporations selling everything from magazines to gardening equipment.

Now he runs a Finnish start-up where socks are the norm on the office floor, and he proudly sports a round-neck T-shirt spun from recycled clothing fibres, tucked into some baggy shorts.

His firm, Infinited Fiber, has invested heavily in a technology which can transform textiles that would otherwise be burned or sent to landfills, into a new clothing fibre.

Called Infinna, the fibre is already being used by global brands including Patagonia, H&M and Inditex, which owns Zara. "It's a premium quality textile fibre, which looks and feels natural - like cotton," says Mr Alava, rubbing his own navy blue tee between his fingers. "And it is solving a major waste problem."

Around the world, an estimated 92 million tonnes of textiles waste is created each year, according to non-profit Global Fashion Agenda, and this figure is set to rise to more than 134 million tonnes by 2030, if clothing production continues along its current track.

Infinna fibre is derived from unwanted clothes and textiles

To the untrained eye, samples of Infinited Fiber's recycled fibre resemble lambswool; soft, fluffy and cream coloured. Mr Alava explains that the product is produced through a complex, multi-step process which starts with shredding old textiles and removing synthetic materials and dyes, and ends with a new fibre, regenerated from extracted cellulose.

This finished fibre can then simply "hop into the traditional production processes" used by High Street brands, replacing cotton and synthetic fibres, to produce everything from shirts and dresses to denim jeans.

Much of the science involved in making the fibre has been around since the 1980s, says Mr Alava, but rapid technological advancements in the last few years have finally made large-scale production a more realistic possibility.

In parallel, he believes High Street brands have become more focused on "really honestly looking for changing their material usage", while millennial and Gen Z consumers are increasingly concerned about shopping sustainably. "They are different animals, different consumers, to people my age," he laughs.

Infinited Fiber says its material can replace cotton and synthetic fibres

The company has already attracted so much interest in its technology that it recently announced it was investing €400m (£345m; $400m) to build its first commercial-scale factory at a disused paper mill in Lapland.

The goal is to produce 30,000 tonnes of fibre a year once it's operating at full capacity in 2025. That is equivalent to the fibre needed for approximately 100 million T-shirts.

"I think the impact could be quite big, if you think about the whole textile system, what exists currently and how much textile waste that we have," argues Kirsi Niinimäki, an associate professor in fashion research at Aalto University, a few blocks away from Infinited Fiber's headquarters.

"It's a really good example of actually how we can 'close the loop'… really begin to move to a circular economy."

Infinited Fiber's growth is tied into a wider vision in Finland, which wants to become Europe's leading circular economy, with a focus on reusing and saving resources. In 2016, it became the first government in the world to create a national road map designed to help reach its goal.

Several other Finnish start-ups are looking at ways to produce new textile fibres on a big scale, while also cutting down on harmful emissions and chemicals. These include Spinnova which, from its textiles factory in Jyväskylä, central Finland, transforms cellulose from raw wood pulp into ready-to-spin fibres.

It has partnered up with Suzano, one of the world's leading pulp producers, headquartered in Brazil. And, the company says its spinning technologies can even be used to create new fibres from a range of other materials that can be turned into pulp, from wheat straw to leather offcuts.

Janne Poranen hopes Spinnova will become a household name

"Of course, the volumes are tiny at the moment, [but] our plan together with Suzano is that in the next 10 years we are going to upscale up to one million tonnes in annual volume," says Janne Poranen, one of Spinnova's co-founders.

He is less specific about how exactly that is going to happen, though, refusing to give any financial projections and admitting that the company has yet to decide which continent its first large-scale production plants outside Finland are likely to be built on.

Still, Spinnova's yarn is attracting plenty of global attention and has so far been used by brands including upmarket Finnish clothing label Marimekko, and outdoor wear firms North Face, Bergans and Adidas, which recently used it in a limited edition midlayer hoodie designed for hikers.

Mr Poranen has big ambitions for Spinnova-woven products, hoping they can gain a reputation for being sustainable and long-lasting, in a similar way to how Gor-Tex became a household name for its waterproof technologies.

Spinnova fibres are made from cellulose from raw wood pulp

Elsewhere in Europe, there are a range of other companies developing technologies to create more circular yarns, including Swedish startup Renewcell, and Bright.fiber Textiles, which plans to open its first factory in the Netherlands in 2023.

But experts say there are a range of challenges facing these new fibre brands as they plot their expansions.

Ms Niinimäki underlines that the clothing manufacturing sector has, until recently, been slower than many other industries when it comes to embracing sustainability, which could set the tone for a slower transformation than companies like Spinnova and Infinited Fiber hope.

"It has been so easy to produce the way that we have been producing, and just to move towards more effective industrial manufacturing on an increasingly bigger scale," she says.

"There hasn't been a big pressure to change the already existing system." However, she is hopeful that, in the European Union at least, new rules aimed at ensuring clothing manufacturers focus on more sustainable and durable products will speed up "a change in mindsets".

Another issue is whether clothing brands will be able to pass on the additional costs of their new high-tech production techniques on to consumers, especially at a time when the cost of living is spiralling globally.

Adidas makes a hoodie from Spinnova fabric, but it's not cheap

Adidas' latest limited edition hoodie produced with Spinnova fabric costs €160 (£137; $160) to buy online in Finland, at least €40 more than most of its other technical hoodies.

"Fashion is a complicated area, because even if people are saying that they are environmentally aware, they don't always act rationally," says Ms Niinimäki. "There's also this kind of emotional side when you talk about fashion consumption, and of course, the price is also linked to that."

While both Infinited Fiber and Spinnova insist their business plans look holistically at all aspects of production - for example using renewable technologies to power their factories - climate campaigners argue it is still too early to accurately estimate the net effect of these new techniques on carbon emissions.

"Pulp and other alternative fibres can provide diversity for sourcing textile materials and therefore lessen the burden caused by production of more traditional textile raw materials such as cotton," says Mai Suominen, a leading forest expert for WWF. "However it depends on the use of energy, all the processes they use and how they use waste materials."

Most importantly, she argues, simply slotting more sustainable fibres into the multibillion dollar fashion industry won't be enough to combat climate change, if we keep making and buying clothes at the current rate.

Mai Suominen says there needs to be clear targets for reducing resource use

"There is no sustainable development unless the overall natural resource consumption is radically decreased to a level that fits within planetary boundaries," she argues.

But within the Finnish fibres industry there is a sense of boomtown optimism that the increased use of recycled or reimagined fibres could be an important part of the jigsaw in the battle to limit climate change.

"The fast-fashion companies who have been kind of creating certain parts of the problem are highly interested in new technologies," says Infinited Fibers chief executive Petri Alva. He believes that if investment continues, the recycled fibres could become mainstream within ten to 15 years.