India's solar-powered future clashes with local life

- Published

The deserts of western Rajasthan are an unforgiving place

"Bhadla is almost unliveable," says Keshav Prasad, the chief executive Saurya Urja, a renewable energy company.

He is talking about part of the Thar desert located in Rajasthan in the northwest of India.

Temperatures there can top 50C and frequent sandstorms add to the inhospitable conditions.

But what makes Bhadla an unforgiving place to live also makes it an ideal place to generate solar power.

Thanks to the abundant sunshine, Bhadla is home to the world's biggest solar power farm, in part built and operated by Mr Prasad's Saurya Urja.

Soaking up the sunshine are 10 million solar panels with the capacity to generate 2,245MW, enough to power 4.5 million households.

While keeping the solar panels clean in such a sandy and dusty environment is a challenge, Mr Prasad says running such a vast solar plant is still much simpler than operating almost any other kind of power station.

"There is not much equipment involved. Solar panels, cables, inverters and transformers are almost all that are needed to run a plant," he says.

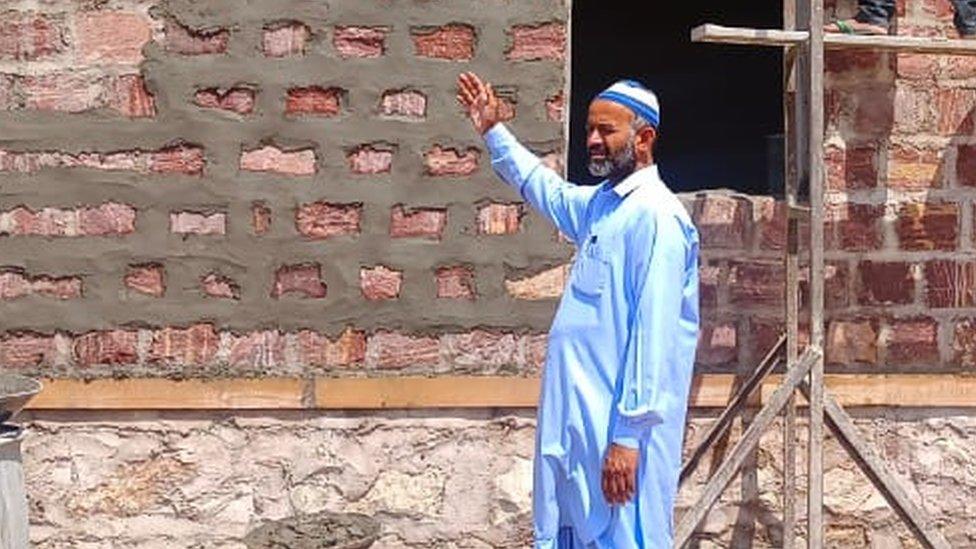

The solar plant in Bhadla has brought new opportunities, says Mukhtiyar Ali

The plant, which was completed in 2018, has brought investment and opportunities to one of India's most remote regions.

"Most of the boys in my village did not study much. They were not ambitious, as our life was limited to the village, and our parents are farmers or into breeding cattle. But since the construction of the park, I realised the world is much bigger than my village," says 18-year-old Mukhtiyar Ali.

"Because of Bhadla Park many engineers, officers and educated people visit our villages, which has changed my perspective towards life.

"I want to be an officer [in the solar park] who has authority, respect, someone who can bring change in other people's lives," he says.

But not everyone is thrilled about the giant solar park that has been built on their doorstep.

Most of the 14,000 acres used for the park were owned by the state, but it was also where local farmers grazed their cattle.

Sadar Khan, the head of Bhadla village, says locals have not seen the benefit of the massive solar farm on their doorstep

"Most of our livelihood was cattle rearing," says Sadar Khan, the head of Bhadla village.

"Because all the government lands have been taken back, we don't have enough land for cattle grazing. We are left with few animals," he says.

He accepts that jobs have been created by the park, but says many of those jobs do not pay enough to survive on.

"There are not many solar jobs for locals except labourers, as most of us are uneducated."

Mr Khan also complains that many locals still have no electricity connection.

"We produce electricity, but still a number of villages in the nearby area are without electricity. So it's good we are the largest solar park - but it should bring changes in our life."

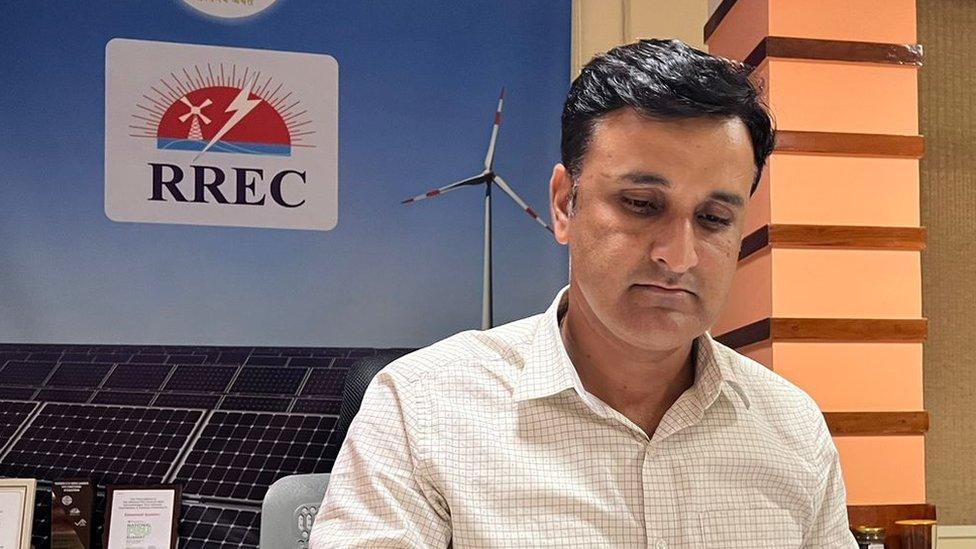

Anil Dhaka, the managing director of Rajasthan Renewable Energy Corporation, disputes Mr Khan's complaints. His state-owned organisation oversees renewable energy projects in Rajasthan.

Anil Dhaka says big projects like Bhadla are bringing down the cost of renewable energy

"As far as Bhadla Park is concerned we have not received any official grievance or complaints regarding land compensation. The land used in Bhadla Park was government land," he says.

Mr Dhaka adds that investments in solar projects in western Rajasthan have caused land prices and rents to rise, so many smallholders have benefited.

He also explains that the issue of electricity connections is not a simple one. The electricity generated by the Bhadla solar plant is at a high voltage, so cannot be directly supplied to local villages.

But he points out that plants like Bhadla are significantly lowering the cost of electricity from renewable sources.

About 75% of India's electricity is generated by burning coal, external, but by 2030 the government wants 40% of its electricity to come from renewable sources like solar.

That is going to require a lot of land.

If India were to put in place a target to be net-zero emissions by the middle of this century, then it would have to cover between 1.7% and 2.5% of the country's total land mass with solar panels, according to a study last year, external by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA).

Currently 34 big solar projects are at various stages of development, so more conflict over their location is likely, experts say.

"A massive shift to renewable energy requires enormous resources, and land is a crucial one," says Bhargavi S Rao, a senior fellow at the Environmental Support Group.

"Rain-fed and irrigated lands are being identified as dry land, drought-prone wasteland, non-productive land and so on, all to ensure such lands can be made available for the land-guzzling, utility-scale renewable energy projects, especially solar and wind," says Mrs Rao.

"The prevailing model of promoting mega-energy projects that are land-intensive is creating an anomalous situation wherein farmers, in certain regions of interest to energy developers, are being surrounded by powerful real estate developers, and also state-led instruments, to compel them to lease and even sell their land," she adds.

Ten million panels cover 14,000 acres at the Bhadla Solar Park

Mrs Rao says, so far, the problem is "sporadic" as the shift to renewable energy is at an early stage. But given the scale of planned developments the situation is going to get worse.

"By 2030 farmers will be under severe pressure to part with their lands. This is going to be especially problematic for small and marginal farmers, who form a majority of the farming community."

When contacted by the BBC, the government did not want to respond to Mrs Rao's claims.

But back in Bhadla, Mr Prasad, the man in charge of Rajasthan's renewable energy projects insists the giant solar plant there has been good for the local community.

"There are around 60 villages around the solar park that have benefited - jobs have been created, schools have been constructed.

"There were no medical facilities but now mobile medical vans visit villages, so this is not all about green energy - it's also the progress of the people."