What is corporation tax and who pays it?

- Published

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt has confirmed that corporation tax will rise from April 2023.

But he has also announced a scheme that will allow companies to reduce the amount they pay if they invest in their businesses.

How much is corporation tax and who pays it?

Corporation tax is paid to the government by UK companies and foreign companies with UK offices.

It is charged on their profits - the amount of money companies make, minus their costs (money spent on things like staff and raw materials).

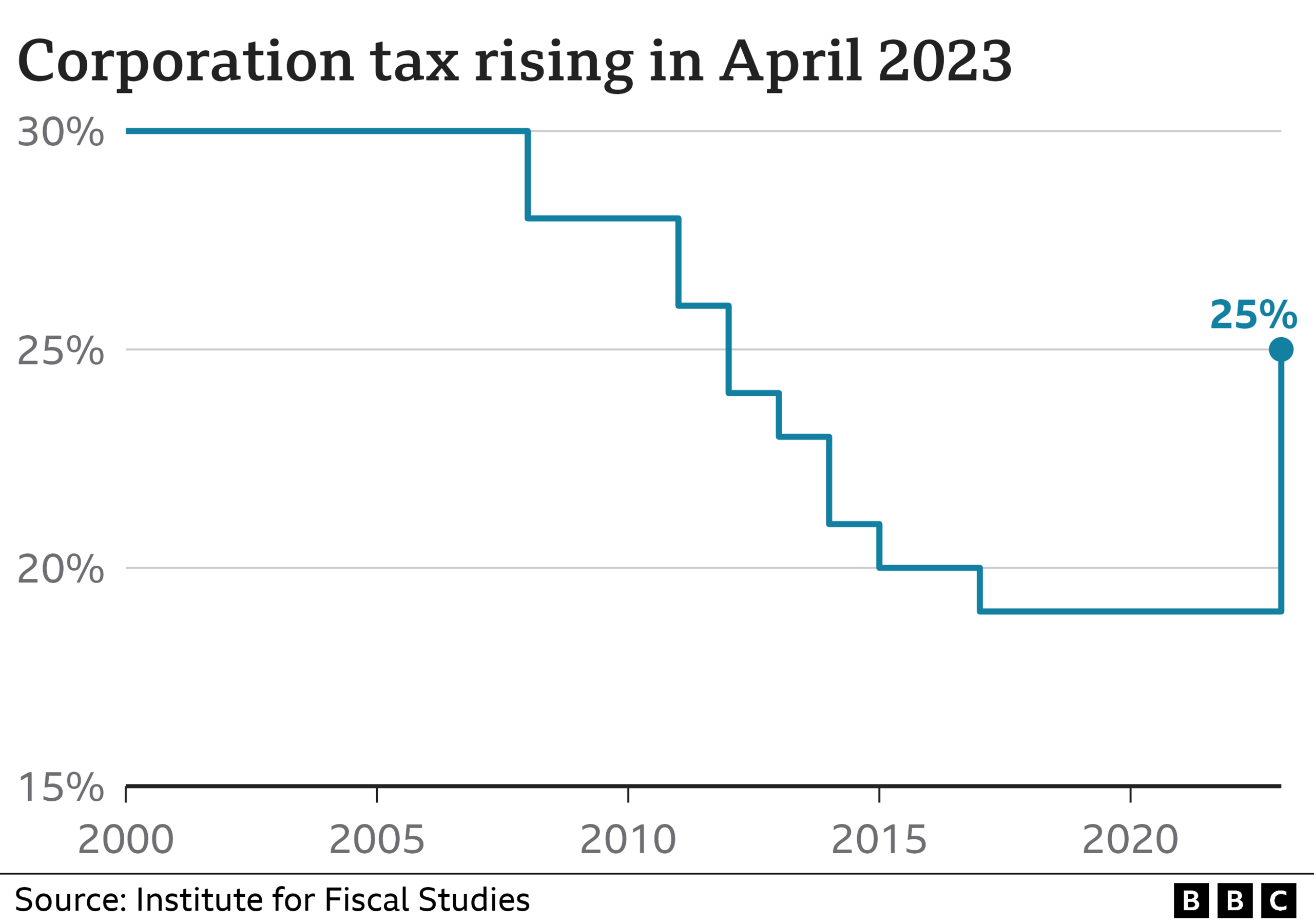

The tax is currently charged at 19% of profits. From April 2023, this rate will rise to 25%.

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) estimates this will raise about £20bn a year by 2027-28.

Small businesses with profits of less than £50,000 will continue to pay 19%. The tax rate will increase gradually for companies as their profits rise from £50,000 to £250,000.

The government will also allow businesses to subtract money they invest in things like IT equipment and machinery from the profits they pay corporation tax on, for the next three years.

Because it's only a temporary measure, the OBR says it will not change overall business investment - instead it will increase investment for the next three years and it will fall after that.

But the independent forecasters said if it was made permanent, as Jeremy Hunt said was his aspiration, it would cost about £10bn a year.

What has happened to corporation tax since?

The rate of corporation tax was cut rapidly by the Conservatives: from 28% when the party came to power in 2010, to 19% in April 2017.

In March 2021, Rishi Sunak - who was chancellor then - announced the rise in the tax. He said companies should pay more because they'd received so much support from the government during the Covid pandemic.

In July 2022, during the Tory leadership campaign, Liz Truss said she would reverse Mr Sunak's decision and keep corporation tax at 19%, to attract investment into the UK.

On 23 September, after Ms Truss had become prime minister, the then chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng announced corporation tax would indeed stay at 19%.

The extent of the unfunded tax cuts in their "mini budget" - which also included changes to National Insurance and the top rate of income tax - caused problems on financial markets.

The cost of borrowing for the government and for mortgages both rose considerably and the pound fell against the dollar.

On 14 October, Ms Truss sacked her chancellor and reversed the decisions, saying corporation tax would go up to 25% after all.

On 17 November, new chancellor Jeremy Hunt confirmed the increase.

What do other countries do?

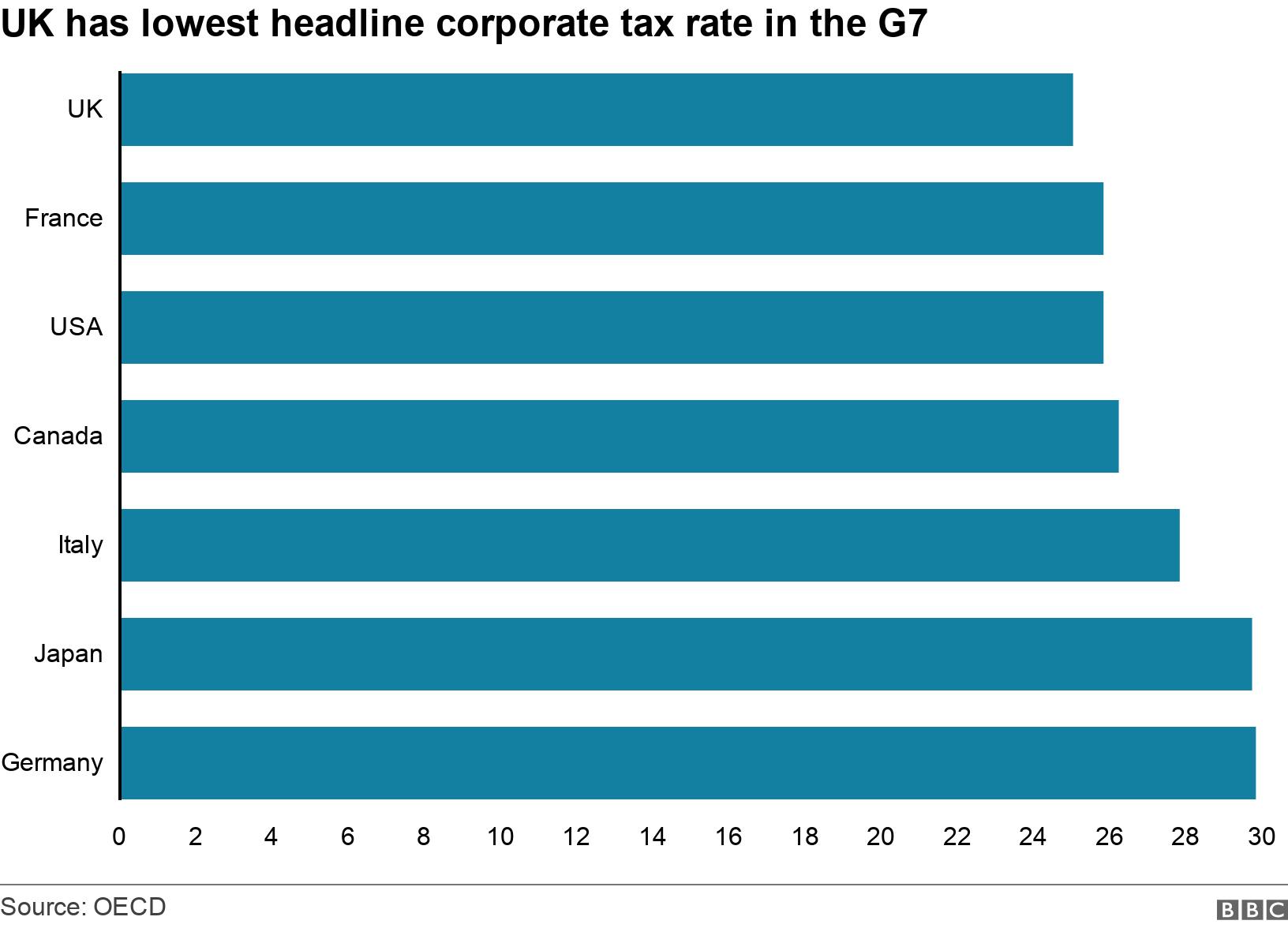

The UK's 19% headline rate of corporation tax is lower than other countries in the G7 group of big economies.

The next lowest country for corporation tax in the G7 is France at 25.8% - higher than the UK even once it increases in April.

But this chart doesn't tell the full story.

Governments leave loopholes. Companies may pay less tax if they invest in their businesses for example, or set up in certain parts of a country.

So the taxes that companies actually pay can look very different to the headline rates of tax charged.

The headline level of corporate tax among the 27 EU countries varies: from the lowest of 9% in Hungary, 10% in Bulgaria and 12.5% in Ireland to the highest of 31.5% in Portugal, 29.8% in Germany and 27.8% in Italy.

Another way of looking at this is how much is raised in corporate taxes as a proportion of the size of the economy measured by GDP.

The UK's tax take as a proportion of GDP puts it third in the G7 behind Japan and Canada, where it is expected to stay even after the increase to the headline rate.