Why smart thermostats don't always save you money

- Published

The makers of smart thermostats say the devices can cut energy bills

A few years ago, Dominic McCann realised that his smart thermostat was a treasure trove of data. So he decided to hack it, in order to track what his boiler was doing literally every minute of the day.

Using open source software, he accessed data from the thermostat online and plotted graphs that charted boiler activity against the changing temperature of a particular room. And when he upgraded the bi-folding door in his dining room to a triple-glazed model, the system instantly captured the difference that made.

"I could quickly get a handle on, 'Oh, if I do this, I've saved this amount of energy,'" he recalls. Insights like this helped him to save money, over time.

Mr McCann, who lives in Manchester, was aided by his technical background. He is director of Azymuth Acoustics UK, a noise assessment firm. When he first tinkered with his thermostat, back in 2019, he was arguably in a small minority.

Dominic McCann hacked his smart thermostat to find out more about his energy use

But with rocketing energy prices, and the associated cost-of-living crisis, more people are turning to their smart thermostats seeking answers to the question: how do I reduce my energy bill?

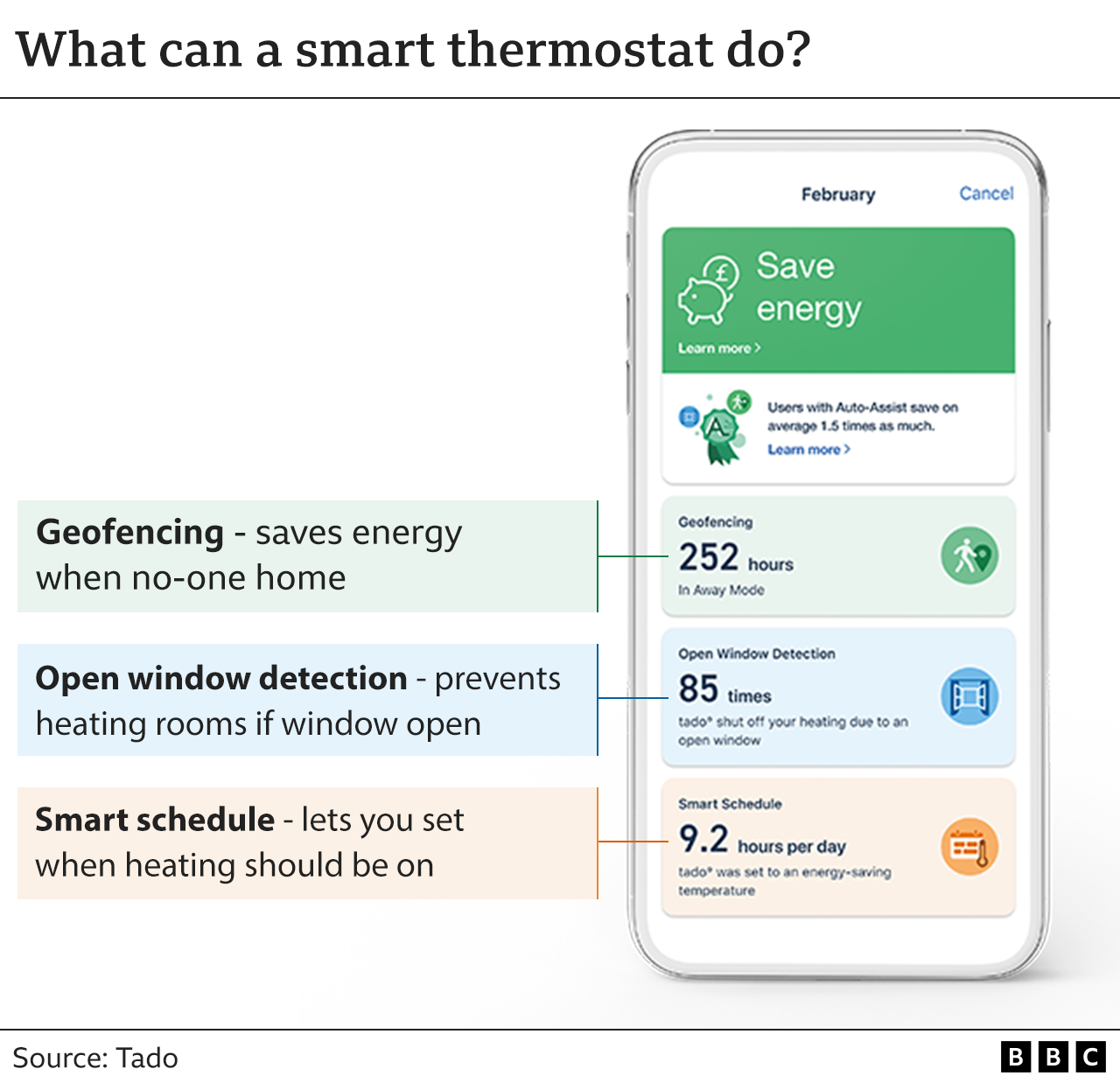

Generally speaking, a smart thermostat is a connected version of a traditional central heating controller - one you can program and adjust via a smartphone or tablet app, or smart speaker.

Manufacturers have long touted these gadgets as money savers. Over the years, they have certainly provided increasingly detailed information about users' energy consumption and offered partially automated heating control.

And yet there is still debate over how beneficial smart thermostats are, with some research indicating that installing one doesn't always result in reduced energy use.

Google Nest, Honeywell, Drayton Wiser, Tado, Hive - all these brands say their systems make it easier to manage your heating. And many offer to learn how you heat your home, or detect when you're out, and respond automatically in an effort to curtail usage and save you money.

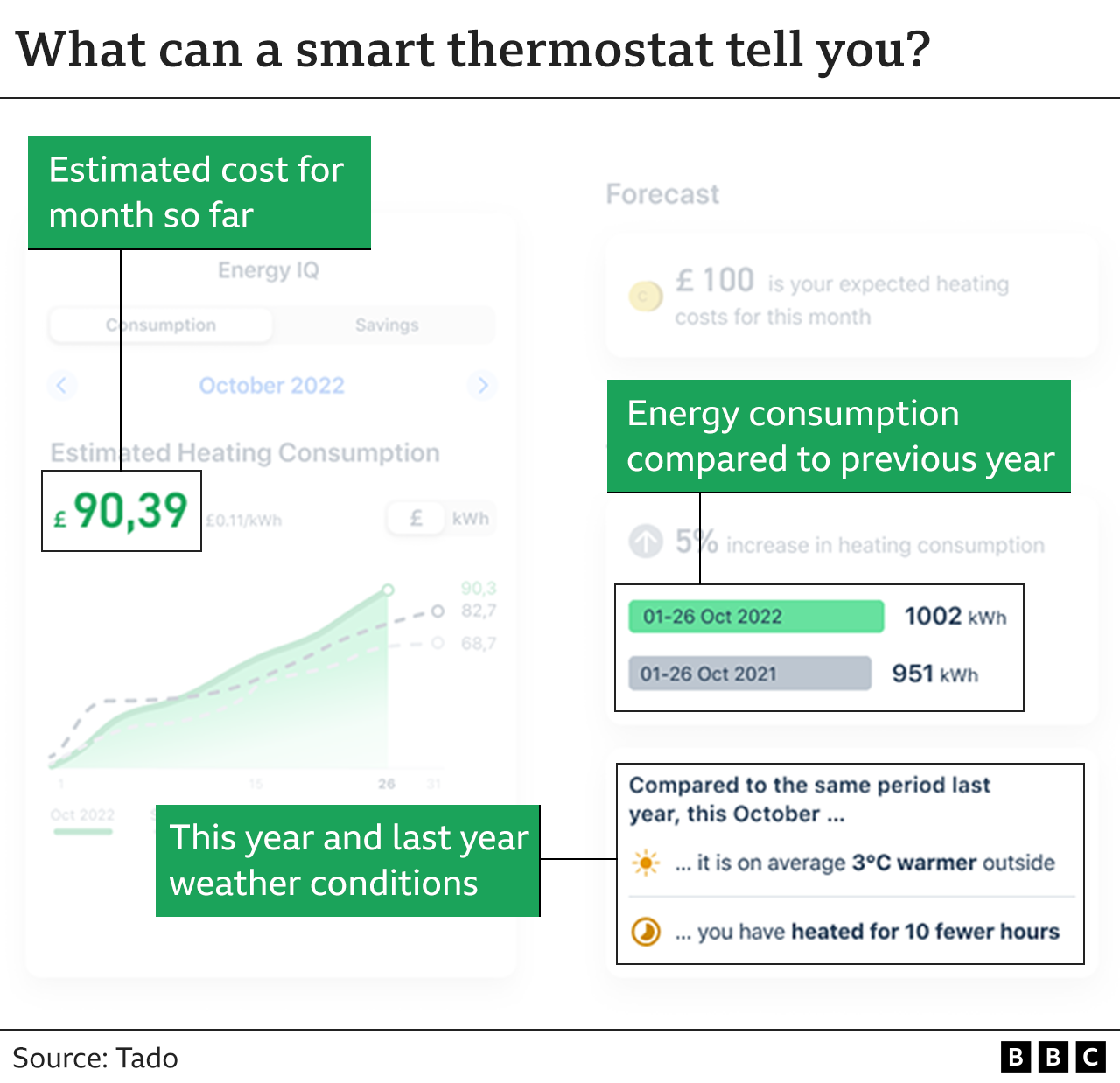

Mr McCann was arguably ahead of his time. In response to the cost-of-living crisis, smart thermostat maker Tado recently launched a software update that provides monthly bill predictions to help users keep within a budget. There are also room-by-room comparisons so people can see which rooms in their home require the most heating.

A spokesman for Tado says that the "vast majority" of its users are able to save money with its system.

There are more than 75 million smart thermostats installed worldwide and this number is expected to more than double by 2025, according to Neil Barbour, an industry analyst with S&P Global Market Intelligence.

He cites research from The American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, external, which estimated that smart thermostats enable a roughly 10% reduction in home heating and cooling per household.

With that in mind, Mr Barbour and his colleagues have calculated that the US could reduce its total energy consumption by 45.4 terawatt hours - roughly the same amount of energy used by the entire state of Mississippi in 2020 - if every home with a heating, ventilation and cooling system installed a smart thermostat by 2026.

That would be quite a saving. But the research on how people actually use these devices paints a mixed picture. One study of Honeywell smart thermostat data from 1,379 households in California, published in September, external, found that users generally undid the benefits of the gadgets by manually overriding their scheduled programme of heating or cooling.

In other words, it was easy to boost the heating, for example, which meant some people eroded their energy savings.

The work of a smart thermostat can easily be disrupted by a manual override

However, a separate analysis published in 2020, external of data from 20,000 Ecobee smart thermostats in the US found that users sometimes overrode their device's schedule in a way that used less energy. So manual interventions, overall, were not as costly as expected. The study was part-funded by Ecobee.

Smart thermostats may struggle when users expect them to do all the work for them, suggests the lead author of the second study, Brent Huchuk, who now works for tech firm PassiveLogic.

According to him, someone who is good at tweaking their own system is likely to do better than a smart thermostat.

"It's pretty hard to beat someone who's actively managing [their] heating and cooling schedule," he says.

He also notes that the automatic interventions of smart thermostats will be limited when people work from home, since that reduces the number of opportunities the smart device has to shut the heating off.

There are also technical quirks to be aware of. In the UK, for instance, some highly energy efficient boilers on the market can modulate (adjust up or down) how much energy they use, in response to the amount of heating required.

But to take full advantage of this, you have to choose a smart thermostat that is fully compatible with your specific model of boiler. The Heating Hub, an independent consumer advice organisation, has published details about this online, external.

"It's such a minefield for households," says founder Jo Alsop.

Brent Huchuk says a smart thermostat might not be as effective as someone managing their heating closely

In the future, smart thermostats could theoretically track energy prices in real-time and allow people to heat their homes when it is cheapest to do so, suggests Dr Huchuk.

A 2017 study by Enrico Costanza, external at University College, London, and colleagues, experimented with exactly this idea. Participants received specially designed thermostats that displayed sample pricing data moment-by-moment.

That might be a little too much information for many. But the study suggested that, across multiple households, this could prompt a reduction in overall energy consumption.

Prof Costanza argues that, in reality, it would be more useful to give people information about their energy use over a longer period, say a month, or a forecast that explains how much someone could save by heating the house a little less in the morning, for example.

"Making it easier for people to understand how they spend energy can make a difference," says Prof Costanza.