Why does the government want to cut spending?

- Published

From nurses' salaries to school supplies and state pensions, over £1 trillion will be spent on public services and investment this year.

Government spending has only been entirely matched by money raised from taxes in six of the last 50 years.

It is more typical to have an annual shortfall averaging about 3% of the money the UK economy makes per year.

But this is not the infamous "black hole", which refers to a future sum shaped by the government's own target.

Let me explain.

What is the government's black hole?

The government can raise enough money to fund its spending by borrowing on financial markets via bonds, which are essentially IOUs. To borrow at relatively low rates, it needs to persuade investors that it's a good bet.

So markets expect governments to draw up and meet rules about how much they should borrow and how that debt is managed, to prove that they are financially responsible.

We won't know the government's exact target until the Autumn Statement on Thursday. But it has indicated, as is fairly standard, that it will bring down the size of the debt - the sum of all our outstanding annual deficits - relative to our national income, in the medium term (typically, five years).

It's the extra money the government needs to find to meet that self-imposed target in the future that's been labelled the black hole.

How big is the hole?

Covid-related support packages pushed government borrowing to its highest level since the end of World War Two. Now the cost of help for energy bills and tax cuts has raised fresh concerns about debt.

Much depends on how the economy fares but the independent Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) reckoned that, after September's tax-slashing mini-budget, over £60bn may be needed in 2027 just to stabilise the size of debt relative to national income.

Many of September's tax cuts have since been reversed, but some economists still predict the government may have to find tens of billions of pounds by 2027 if it imposes such a target. The figure is uncertain, it will depend on the measures in the Autumn Statement, and the forecasts, assumptions and judgement of the government's independent watchdog, the Office for Budget Responsibility.

Does the government need to worry about the hole?

We don't have to look far for a cautionary tale.

September's mini-budget caused market uproar as investors feared the largest tax cuts for 50 years would leave the UK at risk of borrowing more than they were comfortable with, and also push up inflation. Those risks prompted bond investors to look for a higher return, so the interest rate - or yield - on those bonds soared, potentially adding billions to the cost of new government borrowing.

All governments crave faster economic growth but a prolonged recession is forecast for the UK

As it is, higher interest rates and inflation are already causing the government's interest on borrowing to balloon - we were already set to spend twice as much on debt interest as on defence.

Following the deluge of tax U-turns, government bond yields fell back. But the lesson is clear: ignoring a black hole is costly when you're looking to financial markets for funding.

There wasn't a similar market reaction when the government was running up big bills to support the economy through Covid as it had a willing customer for its extra debt. The Bank of England was then running its own support programme - quantitative easing - which ultimately involved buying many bonds. But that was an emergency support measure, and is being unwound.

Why can't a government just print money to fund its plans? It may be tempting, but particularly in a time of rapid inflation, that could just put more pressure on prices.

How can a government fill a black hole?

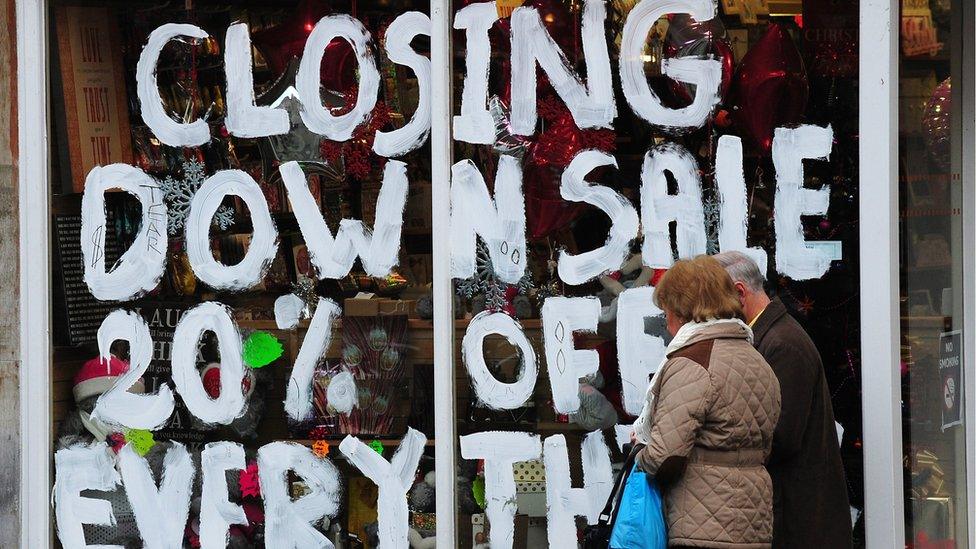

The magic bullet all governments crave is faster growth. That brings in more money through taxes, reduces spending on benefits and would shrink the debt compared with the size of the UK's income. But with warnings of a prolonged recession, it would be unrealistic to gamble on that.

How the government decides to find the cash, how the burden is split between tax rises and spending squeezes, is perhaps more of a political decision than an economic one.

And it may be undeniably painful when the sums are potentially so large. By way of illustration, the IFS says that saving £35bn would be equal to slashing the budget for all centrally funded public services, except defence and health, by 15%. Or, put another way, that sum is equal to more than £1 of every £8 spent on public sector wages.

What about tax rises? Freezing allowances and bands for income tax (stealth taxes) or making changes to inheritance or capital gains tax would pull tens of billions of pounds out of the economy at a time when activities are already set to slump. It would be a risky strategy, as it could prolong the downturn.

Of course, the extra money doesn't need to be found until 2027. Why not wait, and leave tackling the dilemma to whoever wins the next election?

You could, but it's the financial markets that the government is aiming to please, and markets are not known for their patience.

So we'll know who will pay the price very soon. The Autumn Statement may not bring much festive cheer. Instead of pre-Christmas treats, belts may be tightened further in the public sector and tax bills will rise. What it means for our money, we'll find out on 17 November.

Related topics

- Published10 November 2022

- Published17 November 2022