Will the metaverse be your new workplace?

- Published

In the future could your commute to work mean just walking to pick up your VR headset?

When we look back in 50 years' time, it is likely that the 2D internet we now all use will seem laughably archaic.

Not only will the internet likely no longer exist behind a screen, but it is probable that we will interact with it differently.

We'll manipulate objects using augmented reality (AR), explore virtual-reality (VR) worlds, and meld the real and the digital in ways we can currently not imagine.

And what will that mean for the world of work? We are already transitioning away from the nine-to-five commute, and turning our backs on the traditional office setting. This is thanks to two years of pandemic lockdowns, and a newfound love of, or tolerance for, virtual meetings.

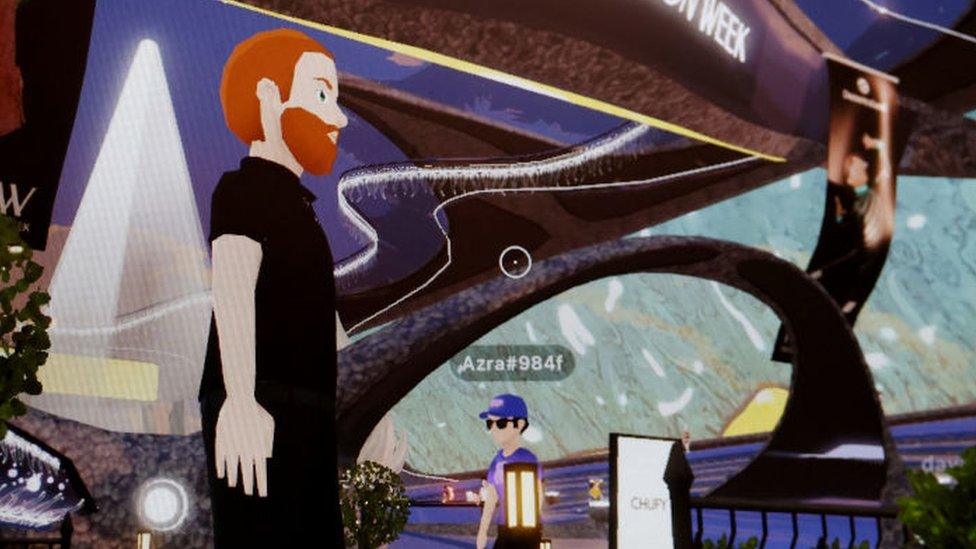

So will the logical next step be working in the metaverse, the planned virtual universe where cartoon-like 3D representations of everyone will walk around, and talk and interact with others?

In the various virtual worlds that one day may merge to form a metaverse you can walk around in avatar form

The metaverse has become an over-hyped term, so it's important to note that it doesn't actually yet exist. And even those invested in the concept disagree about exactly what it will be.

Will rival virtual worlds interconnect in a way that simply doesn't happen at the moment between competing technologies? Will we spend more time there than in the real world? Will we need entirely new rules to govern these new spaces?

None of these questions have answers yet, but that hasn't stopped a barrage of interest and hyperbole as firms see a new way of making money.

We've seen businesses opening in nascent metaverse worlds, from Meta's Horizon Worlds, to games such as Roblox and Fortnite, and newly created lands like Sandbox and Decentraland.

Meanwhile, Nike now sells virtual trainers, HSBC owns land in Sandbox, and Coca-Cola, Louis Vuitton and Sotheby's have presences in Decentraland.

The term metaverse was coined nearly 30 years ago by author Neal Stephenson. In his book Snow Crash, the hero finds a better life for himself in a virtual reality world.

Perhaps the boldest move to make that fiction into real technology came in October 2021. That's when Facebook announced it was changing its name to Meta and started to invest billions of dollars turning itself into a metaverse-first firm - a vision very much led by its founder and boss Mark Zuckerberg.

Mark Zuckerberg has been criticised for his focus on the metaverse

Yet this huge investment has raised eyebrows among shareholders, some of whom recently expressed concern that the firm was spending too much money on VR., external

And a report by The Verge website last October, which claimed to have viewed internal Meta memos, suggested that the Horizon Worlds platform had lots of bugs, and was not well used by employees., external

Herman Narula, the chief executive of Improbable, a firm that makes the software to build metaverse lands, and author of a book called Virtual Society, is not convinced by Zuckerberg's vision.

Herman Narula wants the metaverse to be radically different to the real world

"Why would we want an office in the metaverse that looks like our real office?" he says. "The whole point of creative spaces in new realities is to expand our experiences, not to simply replicate what we've already had in the real world.

"But I do think that there will be a lot of jobs in the metaverse - for example, we're going to need moderators."

The moderating - or policing - aspect of the metaverse is controversial, not just because it is technically hard to monitor potentially billions of avatars having live chats across a virtual world, but because of the vast amount of data those avatars may create along the way.

A study from Stanford University found that spending just 20 minutes in virtual reality provided more than two million unique body movement records,, external a rich new stream of data for firms.

New Tech Economy is a series exploring how technological innovation is set to shape the new emerging economic landscape.

Alex Rice, the co-founder of online security company HackerOne, thinks there needs to be a lot of thought put into the design of the metaverse before any firm can even consider letting their employees loose in it.

"Imagine something innocuous like a water-cooler conversation in an office," he says. "Imagine that it's happening in a fully-monitored metaverse environment - that is certainly going to have life-changing consequences.

"People could be fired outright for saying something they think is in a private, informal conversation with a colleague that is now subject to mass corporate surveillance."

Tom Ffiske, the editor of tech newsletter Immersive Wire, thinks it is far too early to start thinking about working in the metaverse.

Tom Ffiske, here playing a VR game of football, says that working in the metaverse is a long way off for most of us

"Discussing the metaverse is still mired by difficulties, and the definition is still tenuous and debatable," he says. "While the term itself is under discussion and ill-defined, it's difficult to say whether we will be working in the metaverse in the future."

Despite no-one being quite able to get a handle on what the metaverse is, there are some bullish market forecasts for what it may be worth. McKinsey suggests a market value of $5tn (£4.2tn) by 2030, , externalwhile fellow management consultancy firm Gartner predicts a quarter of the world's population will spend at least one hour a day in the metaverse by 2026., external

Matthew Ball, chief analyst at research company Canalys, disagrees - he predicts that most current business projects in the metaverse will be closed by 2025.

He thinks that firms need to reflect whether a presence in the metaverse is actually necessary, or just using tech for tech's sake.

"Not every business needs a VR headset to remotely greet avatars of co-workers, or to visualise virtual models," says Mr Ball. "Nor would every business need VR headsets for meetings. As powerful and compelling as VR is, Zoom and Teams calls offer near-frictionless alternatives that can be less cumbersome."

Tiffany Rolfe is the chief creative officer at RGA, a digital branding firm. She and some of her team have already worked in the metaverse.

Tiffany Rolfe is one of the minority of people to have already spent time working in a virtual world

The firm created a virtual American football stadium in Fortnite for phone giant Verizon during the pandemic, and they also worked with Meta to build a music world within Horizon Worlds.

"People who typically would be on a computer designing things had to put on headsets and work with builders within the world," says Ms Rolfe.

And with new ways of working comes new considerations, such as how long employees should wear a headset for. "My team had probably two-hour stretches where they had it on." she says.

The fact that people are already working in virtual reality worlds suggests that the metaverse could well have a future as a workplace, but the jobs that will exist there are likely to be very different from the those we do in the real world.

And anyone hoping to swap their daily commute for a headset will probably have many years to wait before that becomes a (virtual) reality.