Pay rises at fastest pace for over 20 years, but below inflation

- Published

- comments

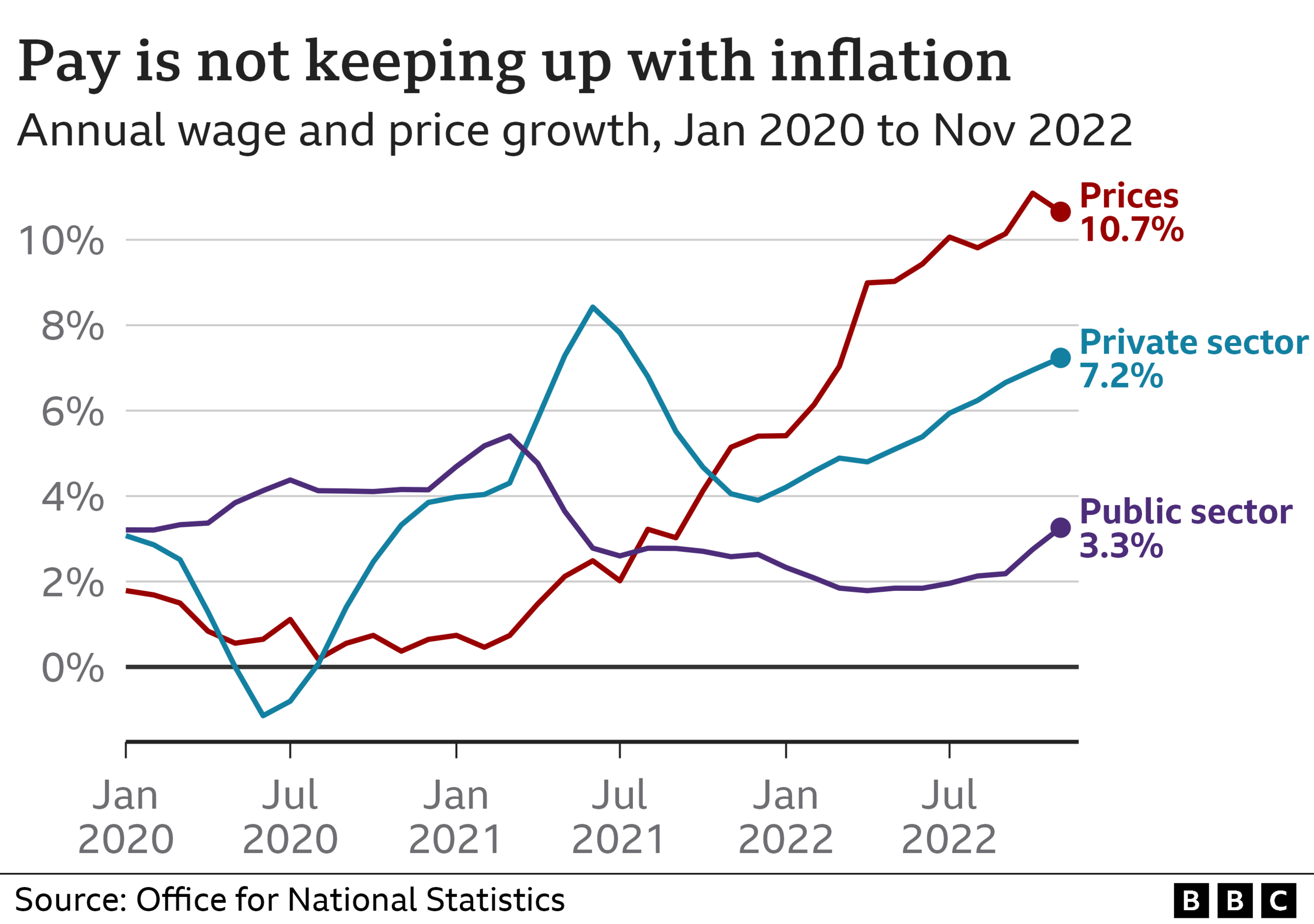

Wages have grown at the fastest rate in more than 20 years, but are still failing to keep up with rising prices.

Average pay, including and excluding bonuses, rose by 6.4% between September and November compared with the same period in 2021, official figures show, external.

It is the fastest growth since 2001, excluding during the height of Covid, but when adjusted for rising prices, wages fell in real terms by 2.6%.

The gap between public and private sector pay is also near a record high.

Private sector wages grew 7.2% annually in the three months to November, which was more than double that of the 3.3% increase in the public sector, according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS).

Pay packets failing to keep pace with the rising cost of living has led to thousands of workers in both sectors striking over pay and working conditions in recent months.

Strikes have disrupted everything from train services to postal deliveries and hospital care, and more industrial action is set to take place in the coming weeks.

In total, 467,000 working days lost were lost due to strikes in November 2022 - the highest number in more than 10 years.

On Wednesday and Thursday, members of the Royal College of Nurses (RCN) will strike in England, while some ambulance staff in England and Wales plan to walk out on 23 January.

Living costs are rising at the fastest rate in almost 40 years, with energy and food prices shooting up, largely due to the war in Ukraine. Inflation, the rate at which prices rise, is currently at 10.7%.

Darren Morgan, director of economic statistics at the ONS, said the "real value" of people's pay was continuing to fall, with regular earnings dropping at the fastest rate since records began once inflation is taken into account.

Workers feeling the pinch has led to people asking for pay rises, but for some businesses, particularly smaller ones, raising wages in line with inflation, at the same time as having to pay for higher energy bills, is difficult.

In addition, worker shortages in some sectors has meant that companies have had to offer more attractive pay packets, with the number of vacancies remaining at historically high levels.

Leanne Wayne, who runs Little Explorers Day Nursery in Golcar, just outside Huddersfield, prides herself on paying above the National Living Wage, which is currently £9.50 per hour for over-23s but will rise in April to £10.42.

Nursery manager Leanne Wayne is preparing to increase fees again this year to pay for higher bills and staff wages

"I would like to put my staff wages up more to reflect how hard they work," she said. "They totally deserve it."

But she added such a decision wasn't a simple one. Not being able to increase wages has also made recruiting new, qualified staff "impossible", Leanne added.

The nursery increased its fees last year and Leanne is bracing herself to do it again in the spring.

The UK's employment rate has remained largely unchanged, while the unemployment rate has edged up marginally, despite fears the UK economy is stagnating.

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has pledged to halve inflation this year, something many forecasters have predicted will happen as the cost of energy falls.

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt said sticking to the government's plan to tackle inflation was the "best way to help people's wages go further". He warned: "We must not do anything that risks permanently embedding high prices into our economy."

But Jonathan Ashworth, Labour's shadow work and pensions secretary, said the government was "totally bereft of ideas when it comes to tackling the cost of living crisis".

Interest rates have been steadily put up by the Bank of England in a bid to try to control rising prices. Raising interest rates makes it more expensive for people to borrow money. In theory, this encourages people to borrow and spend less, and save more.

Ashley Webb, UK economist for Capital Economics, said the fact that the jobs market "remained tight and wage growth remained strong [would] only increase the Bank of England's fears that inflation, despite falling, is still persistent".

It is to be expected in a time of high inflation that wages will grow faster than in a period of low inflation.

The average earnings rise of 6.4% (both including and excluding bonuses) may be the highest in cash terms, but because each pound buys you less and less, it's one of the biggest pay cuts in real terms that we've seen this century.

In contrast to the public sector, you can see clearly private sector wage rises are being driven by employers contending with market forces in the shape of one of the tightest labour markets in decades.

Those in most urgent need of staff are bidding up wages - like in the professional, scientific and technical activities. Employers know that if you ignore market forces in the labour market, you'll find you can't attract the staff you need to do the work. And those market forces are at work across the whole economy, in the public every bit as much as the private sector.

- Published12 February 2024

- Published13 January 2023

- Published13 December 2022

- Published1 August 2023