Pasta price doubles to 95p as cost of basics rises

- Published

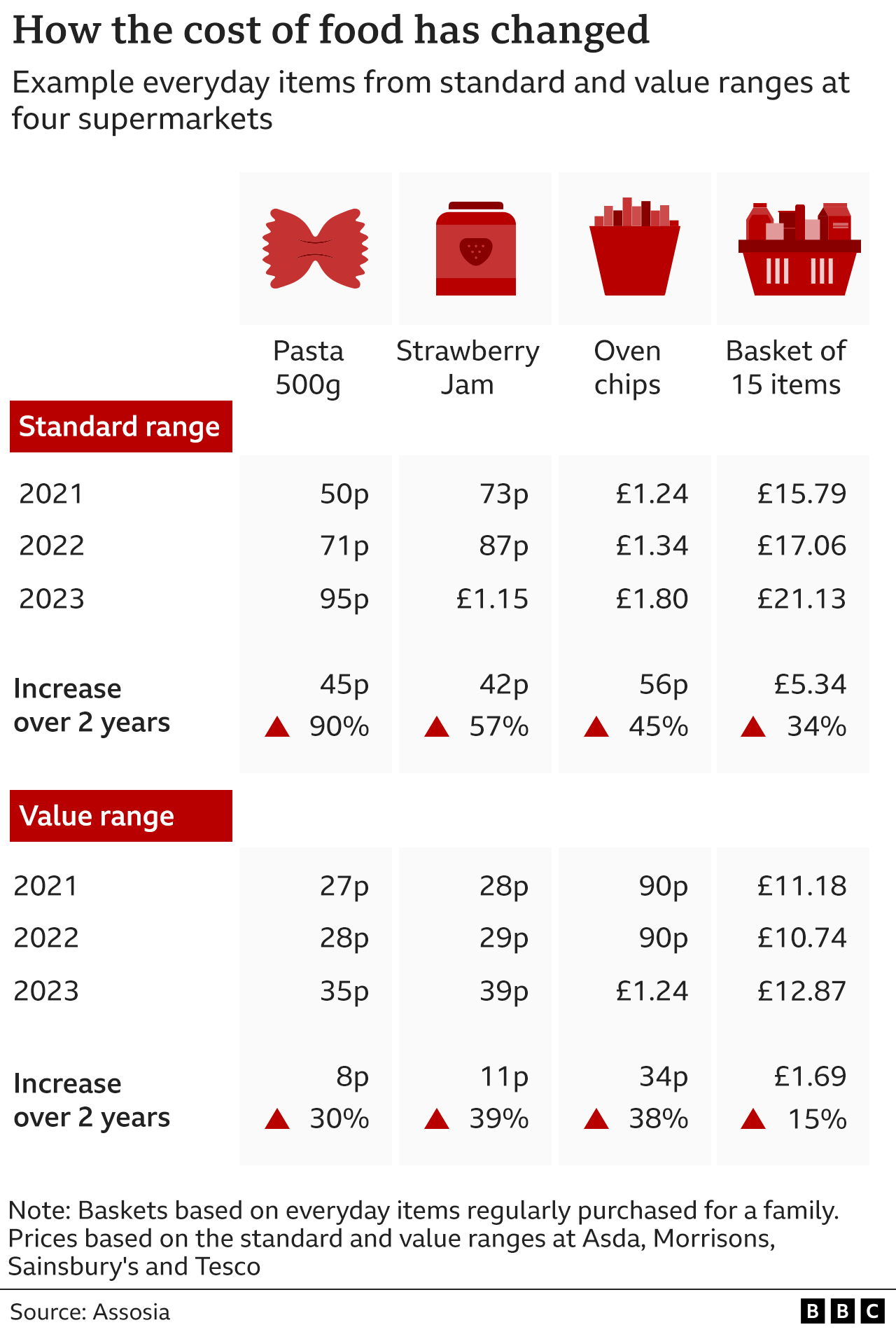

The price of pasta has nearly doubled in two years, new research for the BBC suggests.

A standard 500g bag of pasta was 50p two years ago - now it's 95p.

We've been tracking the cost of a small basket of 15 everyday essentials. The total has gone up by £5.34 - from £15.79 in 2021 to £21.13 in 2023.

Official figures suggest overall UK inflation may have peaked at 11.1% in October. But the rate of food price rises is still running at 16.7%.

Changes in the average cost of 15 food items in January at Asda, Tesco, Morrisons and Sainsbury's were tracked by the retail research firm Assosia.

The items are a mix of everyday essentials, from oven chips and strawberry jam to pasta sauce and potatoes. They were chosen so we could compare some of the most popular items across the value and standard ranges.

If you look at our table below the cost of the standard basket is up by more than a third over the last two years.

The cheaper, value basket, hasn't risen as fast but the rate of increase is much closer to the standard basket over the last year.

Kay Staniland, director at Assosia, said the figures show the real price rises that shoppers are seeing each week.

"It's inflation on top of inflation at the moment," she said.

Prices were already rising rapidly last January and that was before the war in Ukraine which then triggered a huge increase in the price of gas as well as disrupting supplies of grains, vegetable oils and fertiliser. That's when the cost of groceries really started to rocket.

Lag in price rises

According to James Walton, chief economist at the IGD, a research charity in the food and consumer goods industry, it could hit 17-19% in the first half of this year, with the rate of increase starting to fall quickly after that.

Or putting it another way, food prices will still be going up by the end of the year, but more slowly than before.

Food production is incredibly energy intensive. But with wholesale gas prices falling sharply along with a drop in the price of global food commodities, like wheat, why are food prices in our supermarket shelves still rising?

One big reason is the lag between food producers being hit with higher costs and when their products end up in store, said Mr Walton, from the IGD.

"The food supply chain is extremely complicated. The products can change hands many times, before they come to us as the consumer. And so it takes a long time for the costs increases at the start of the supply chain to be passed down all of the steps until we actually encounter them in the store."

There are always prices hikes in January. Retailers try to hold back from increasing the costs of products till after the key Christmas trading period.

According to Assosia, 10,000 products went up in price over the new year - but this is more than double the number that rose in price during the same period last year.

"I'm not surprised… everyone's got increased costs," said Ms Staniland.

Prices will fall

Kitkat maker Nestle, for instance, recently announced it would raise prices again this year despite an 8.2% increase in 2022.

Food shortages don't help. Bad weather has disrupted supplies of fresh fruit and veg which we rely on from overseas at this time of the year. And British growers have been planting fewer crops like tomatoes and cucumbers because of the huge heating costs for greenhouses. They've also struggled to find seasonal labour to pick them.

"They're just not planting enough stuff here because it's uneconomic," says Adam Leyland, Editor-in-Chief of The Grocer magazine.

"We'll have to import more from elsewhere. And that inevitably means inflation because the cost of doing that is higher."

British growers say they need higher prices to survive.

Overall, our food bills look set to get worse before they get better but according to Mr Walton there is light at the end of the tunnel. Assuming no nasty shocks, like a drought, he believes prices will fall at some point in the future, helped by the incredibly competitive nature of grocery retailing in the UK.

"Each of the different parties is watching the other very closely for some sign of negotiating advantage. If a supermarket thinks that the cost of production has come down, well of course they'll bring the supplier into their office and say 'we want our prices to come down as well'."

"The ferocious desire for a better deal is actually what is probably the shoppers best protection against price inflation, " he said.

But there's little respite for shoppers right now.

Related topics

- Published24 February 2023

- Published11 February 2022

- Published18 January 2023