Why food bills aren't shrinking - five things to know

- Published

- comments

Food prices are 19% higher than a year ago. A grocery shop that used to cost £50 is now nearer £60.

That prompted the prime minister to hold a food summit at Downing Street, but it is still not entirely clear where the solution lies.

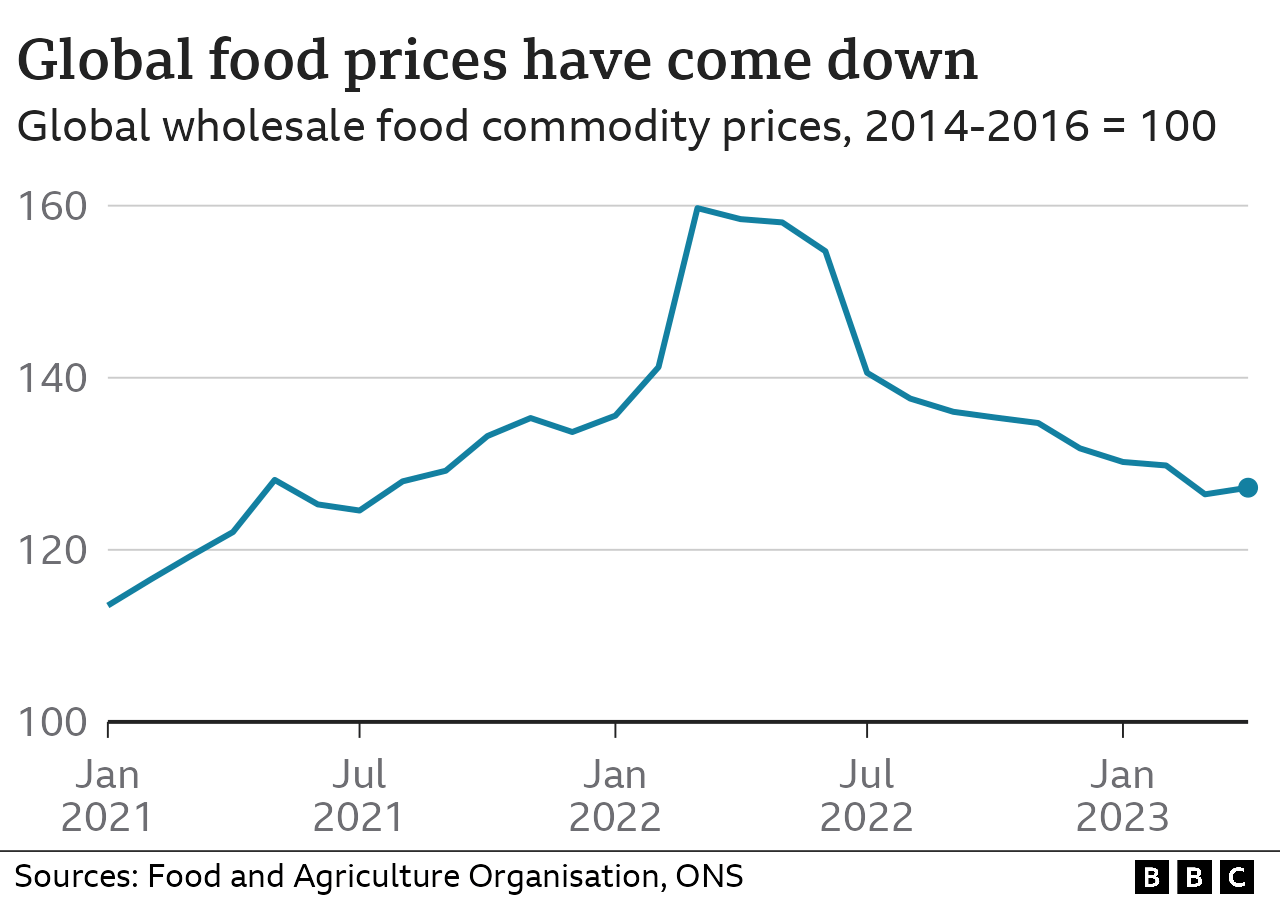

Last year the war in Ukraine pushed up the price of food and energy, but recently those prices have fallen sharply, so why haven't bills?

Here are five things that help explain what's happening.

1. Costs have been eye-watering - but some are easing

Russia's invasion of Ukraine prompted soaring grain, sunflower oil and fertiliser prices. Concerns over supply disruption triggered similar price rises for other foodstuffs.

The UN's food agency found that global wholesale prices for meat, dairy, grain, oils and sugar spiked by about 20% on average after the invasion - but those have since fallen back.

Food production and retailing are particularly energy-intensive industries. Some businesses, without access to the same level of government support as households, saw bills more than triple.

Staffing costs are the other big component for food producers and sellers.

The increase in the minimum wage, labour shortages across the supply chain exacerbated by Brexit, and the rising cost of living meant employers awarded staff pay rises of up to 9% over the last year.

2. Profit margins in the food chain can be slim

All parts of the food chain faced huge shocks when it came to their bills - but did they shoulder their fair share of the burden?

Much of our food chain operates with slim margins, so there's limited wiggle room.

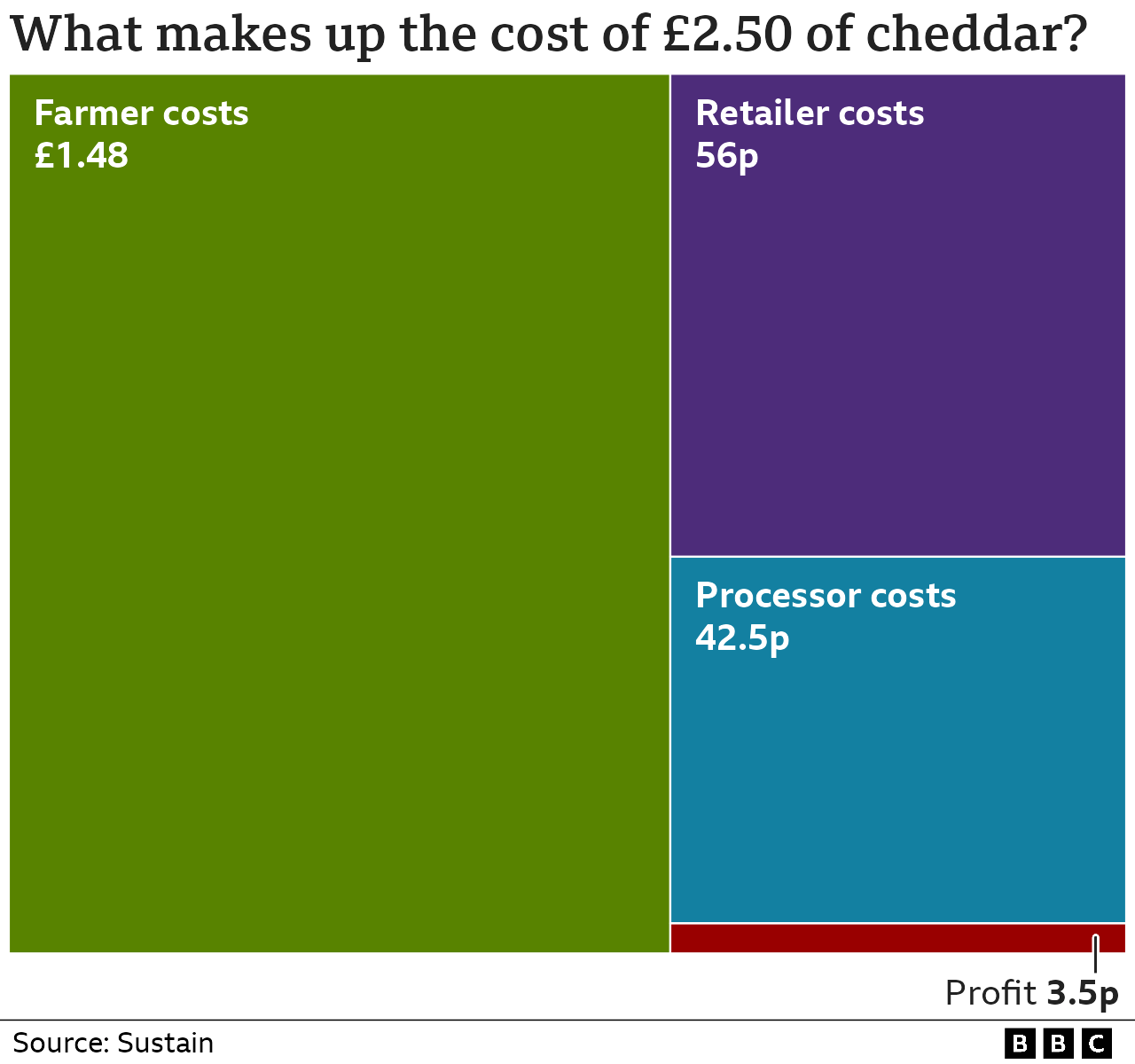

Take a piece of cheddar costing £2.50.

In a study for food alliance, Sustain, academics from the Universities of Portsmouth and London claim farmers' costs account for nearly £1.50 while the retailers' and processors' overheads make up most of the rest.

They reckon that leaves 3.5p of profit to be shared, with the supermarket typically getting 2.5p (1% of the price) while the farmer gets less than a penny.

Arla, the dairy farmers' cooperative, says costs shot up by as much as 80% last year and absorbing those kinds of increases is challenging.

Profit margins on some items - particularly processed food and drinks - are bigger. Unilever, which makes Magnum ice creams, or Premier Foods, the maker of Mr Kipling cakes, may make 15p for each £1 of sales to retailers. As analysts say, the bigger the sin, the bigger the win.

The Unite union has accused the big supermarkets of profiteering, saying the three biggest chains saw total profits double compared with the period prior to the pandemic - but that was in 2021. Since then all parts of the food chain have been hit by unexpected cost hikes.

In total, supermarkets typically make around 5p of profits from each £1 of goods they sell - their profit margin. Last year, Tesco only made around 4p per £1, Sainsbury's closer to 3p.

3. Price changes take a while to travel from farm to fork

Supermarkets are keen to publicise the price cuts they're making for certain items such as pasta, dairy and oil. Those reflect lower costs, but why aren't we seeing bills falling overall?

It's often claimed that retailers are swift to put up prices, but drag their feet on passing on savings when they could be coming down.

However, contracts for goods and services are often agreed many months in advance, which means some producers and retailers will have fixed prices at the very high rates seen last year and they could be tied in to those for months yet.

The good news is that the rate of wholesale inflation that food retailers face, though still high, is now slowing. That should feed through to smaller price rises on shelves - but it typically takes about six months.

We won't know, as many retailers and food suppliers only publish a breakdown of their figures annually, whether some have taken this opportunity to try and rebuild their profit margins. They're under pressure from shareholders to do so. But those figures will, when revealed, face close scrutiny.

4. Prices may be lower than in the rest of Europe

With Brexit adding to the red tape of importing food, are we paying more for our food than shoppers in the EU?

A study by economist Michael Saunders for research body Oxford Economics says not.

Looking at a range of food and drink, he says UK prices are typically 7% below the EU average - with bread, meat and fish in particular relatively cheap. He says the UK's competitive supermarket sector plays a role in keeping prices down.

By contrast, he says that prior to 2015, on average groceries were more expensive in the UK than in the EU - partly reflecting the relatively small influence of the lower cost retailers such as Aldi and Lidl at that point.

5. Smaller bills may not be on the horizon

By the summer, the Resolution Foundation think tank reckons households will have seen an increase in food bills of £1,000 since 2020.

While some items we buy may get cheaper, a return to the kind of smaller bills we saw prior to the pandemic seems unlikely.

Despite recent falls for some commodities the price for many things, from raw ingredients to energy, remain far higher than they were prior to 2020. And there could be other factors looming - the full range of checks and other formalities around food imported from the European continent have yet to be introduced, for example.

Moreover, with costs as they are, farmers are already leaving the business, while the number of food manufacturers collapsing has risen.

How can I save money on my food shop?

Look at your cupboards so you know what you have already

Head to the reduced section first to see if it has anything you need

Buy things close to their sell-by-date which will be cheaper and use your freezer

Related topics

- Published15 November 2023

- Published19 April 2023

- Published29 November 2023