On the warpath: AI's role in the defence industry

- Published

Alexander Kmentt says technology is developing much faster than the regulations

Alexander Kmentt doesn't pull his punches: "Humanity is about to cross a threshold of absolutely critical importance," he warns.

The disarmament director of the Austrian Foreign Ministry is talking about autonomous weapons systems (AWS). The technology is developing much faster than the regulations governing it, he says. "This window [to regulate] is closing fast."

A dizzying array of AI-assisted tools is under development or already in use in the defence sector.

Companies have made different claims about the level of autonomy that is currently possible.

A German arms manufacturer has said, external, for a vehicle it produces that can locate and destroy targets on its own, there's no limitation on the level of autonomy. In other words, it's up to the client whether to allow the machine to fire without human input.

An Israeli weapons system previously appeared to identify people as threats, external based on the presence of a firearm - though such systems can, like humans, make errors in threat detection.

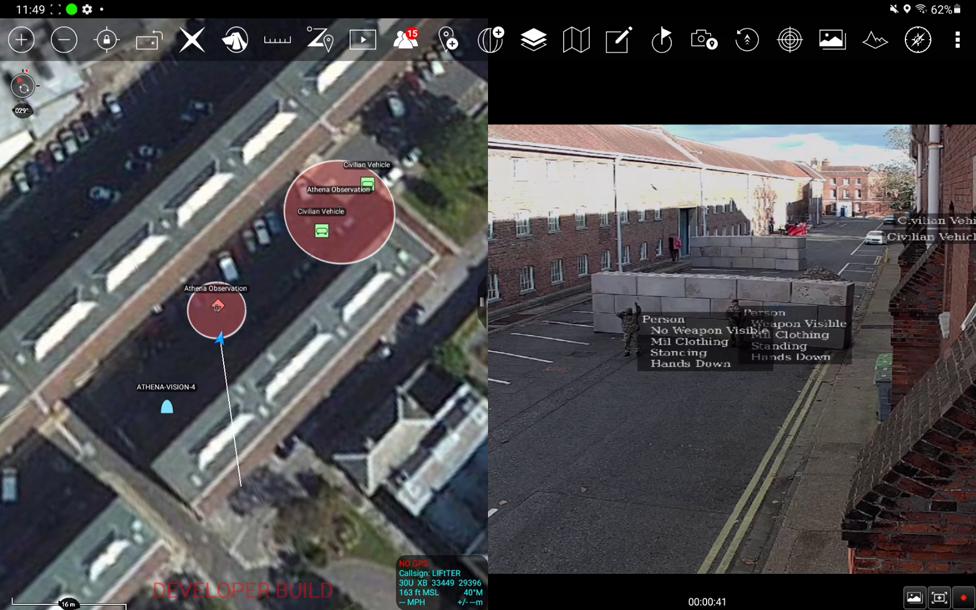

And the Australian company Athena AI has presented a system that can detect people wearing military clothes and carrying weapons, then put them on a map.

"Populating a map for situational awareness is Athena's current primary use case," says Stephen Bornstein, the chief executive of Athena AI.

Athena AI's system can detect people in military clothes and carrying weapons

"Our system has been designed for AI on the loop [with a human operator always involved], so AI does not make targeting decisions. This means the AI aids the human in identifying targets, non-targets, protected objects, no strike lists and plotting weapons' effects," he says.

Many current applications of AI in the military are more mundane.

They include military logistics, data collection and processing in intelligence and surveillance and reconnaissance systems.

One company tackling military logistics is C3 AI. It's primarily a civilian technology firm, but has applied its tools to the US military.

For example, C3 AI's predictive maintenance for the US Air Force aggregates the abundant data from inventories, service histories, and the tens of thousands of sensors that might be on a single bomber.

"We can look at those data and we can identify device failure before it happens, fix it before it fails and avoid unscheduled downtime," says Tom Siebel, the chief executive of C3 AI.

AI can help identify "device failure" before it happens, says Tom Siebel

According to the company, this AI analysis has led to 40% less unscheduled maintenance for monitored systems.

Mr Siebel says that the technology is sophisticated enough to make such predictions - even accounting for randomness and human error.

Overall, AI is necessary given the technical complexity of modern warfare, he believes. One example is swarms of objects like drones. "There's just no way you can coordinate the activity of a swarm without applying AI to the problem," according to Mr Siebel.

In addition, Anzhelika Solovyeva, a security expert in the Department of Security Studies at Czechia's Charles University, says AI can "enhance situational awareness of human pilots in manned aircraft", and even "paves the way for autonomous aerial vehicles".

However, it's in the realm of weapons deployment that people really tend to worry about militarised AI.

The capacity for fully autonomous weapons is there, cautions Catherine Connolly, the automated decision research manager for the campaign network Stop Killer Robots.

"All it requires is a software change to allow a system to engage the target without a human actually having to make that decision," according to Ms Connolly, who has a PhD in international law & security studies. "So the technology is closer, I think, than people realise."

Campaign network Stop Killer Robots gets its message across in Berlin

"Fears of lethal AI are justified," acknowledges Anzhelika Solovyeva, whose PhD is in international relations & national security studies. However, she argues that NGOs and the media have exaggerated and oversimplified a highly complex category of weapons systems.

She believes that AI will be applied in weapons systems primarily to support decisions, integrate systems, and facilitate the interactions of humans and machines. If the actual decision to fire weapons is delegated to AI, she expects it to first be used for non-lethal applications, like missile defence or electronic warfare systems, rather than fully autonomous weapons.

Ms Solovyeva says the future of autonomous weapons is what she and her colleague Nik Hynek refer to as the "switchable mode". "What we mean by this is a fully autonomous mode that human operators can activate and deactivate as they wish."

One argument advanced by proponents of AI-enabled weapons systems is that they would be more precise. But Rose McDermott, a political scientist at Brown University in the US, is sceptical that AI would stamp out human errors.

"In my view the algorithms should have brakes built in that force human oversight and evaluation - which is not to say that humans don't make mistakes. They absolutely do. But they make different kinds of mistakes than machines do."

It can't be left to companies to regulate themselves, says Ms Connolly.

"While a lot of industry statements will say 'you know we will have a man in the loop and it will always be a human deciding to use force', it's very easy for companies to change their minds on that."

Some companies are seeking greater clarity themselves on what kinds of technologies will be allowed.

So that the speed and processing power of AI don't trample over human decision making, Ms Connolly says the Stop Killer Robots campaign is looking for an international legal treaty that "ensures meaningful human control over systems that detect and apply force to a target based on sensor inputs rather than an immediate human command".

She says regulations are urgent not only for conflict situations, but also for everyday security.

"We so often see that the technologies of war come home - they become used domestically by police forces. And so this isn't only just a question of the use of autonomous weapon systems in armed conflict. These systems could also then become used by police forces, by border security forces."

AI can be used to coordinate swarms of combat drones

Although the campaign to regulate autonomous weapons has not produced any international treaties over the years, Ms Connolly is cautiously optimistic about the possibility of international humanitarian law catching up with the technological advancements.

She says previous international agreements on landmines and cluster munitions suggest that international humanitarian law, however slow-moving, can create norms around avoiding certain types of weapons.

Others believe that autonomous weapons systems constitute a much broader and more difficult-to-define category of weapons; and even in the unlikely event of a ban treaty, it would be unlikely to have much practical relevance.

Back at the Austrian Foreign Ministry, Alexander Kmentt says the goal of any regulation should be to ensure "there is an element of meaningful human control on the decision over life and death".

"It's really important that the human element is not lost."