Davos: Global crises set to dominate gathering of business leaders

- Published

Just a week ago, the expectation about the latest gathering of the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, was of a line being drawn under three years of pandemic, lockdown and Ukraine war energy shocks.

Inflation is falling, and 2024 was set to be the year that central banks start cutting interest rates, including here in the UK. In three years of different rolling, merging global crises, the world economy has been in the shadow of massive geopolitical shifts.

The events of the past few days shows that the "polycrisis" is far from over.

Perhaps the most telling development has been the ability of the Houthis to use relatively cheap drones and armaments to cause havoc with world trade. Air strikes on the Houthis in Yemen were carried out explicitly to keep the currents of trade and economic recovery flowing through the straits leading to the Suez Canal.

But oil prices jumped on Friday because the risk of a wider confrontation in the region has also gone up. In three months the crisis in Gaza has led to RAF jets attacking targets in Aden. What will be happening three months from now?

As it happens, this sort of fundamental diplomatic challenge is made for the World Economic Forum. Launched in 1971, and held every year in the Alpine ski resort of Davos, the conference puts together the world's top business people and politicians, as well as key players from charity and academia.

Where else would the Israeli president, Saudi foreign minister and Qatari prime minister be present in the same space at the same time, alongside French President Emmanuel Macron, UK Foreign Secretary David Cameron, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Chinese Premier Li Qiang?

Expectations are low surrounding the grim situation in the Middle East, but this is the sort of place where constructive and unexpected conversations can take place discreetly.

There had been a whiff of decay about Davos since the pandemic. G7 leader appearances were getting rarer. Rishi Sunak hasn't been and isn't going this week. In a huge year for elections across the globe the US delegation this year is particularly thin. Republicans in particular view the event with some suspicion.

The Republican Party's Ron DeSantis, a potential presidential candidate, last year called Davos a "threat to freedom" run by China. The Florida governor said any policies emerging from the forum were "dead on arrival" in his state. The view in Davos is that he thought that such rhetoric would play well in the presidential primaries which also start this week.

Ukraine's President Volodymyr Zelensky is attending, and will be mindful of "Ukraine fatigue" reaching Washington DC and becoming prevalent in developing countries.

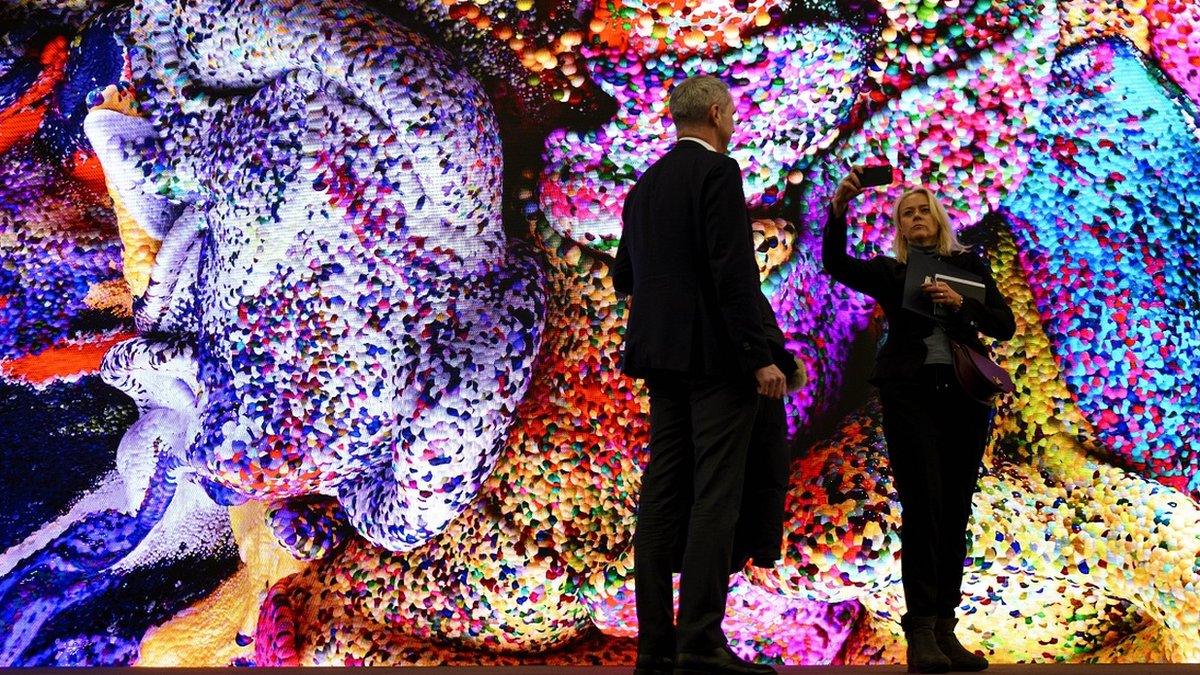

Security is always tight at the Davos gathering

For the UK, some in the business community appear ready to go beyond a curious interest in the Labour Party in this election year.

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt and shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves will be competing for the attention of UK business leaders and international investors.

If business investors are worried about Labour's economic plans, for example for extra investment spending, the World Economic Forum is exactly where it may, or may not surface. I recall then-opposition leader David Cameron's parade of meetings with world leaders, just before he became prime minister in 2010.

There has been a backlash against some of the corporate do-gooding typical of the event, especially the recent focus by investors on companies' environmental and social policies.

Put brutally, the world of the past two years has seen massive returns for hydrocarbon extractors, carbon emitters and arms companies.

The optimism will come from a hope that disturbed geopolitics can somehow settle without a further energy shock.

Artificial intelligence will be everywhere, with the ChatGPT-creating Open AI boss Sam Altman being paraded to the world's business and political leaders by Microsoft, which is now vying with Apple to be the world's biggest company.

So at the start of a delicate year of disorder and uncertainty in global politics and diplomacy, and question marks about economic recovery from years of such crisis, it is difficult to imagine a better moment for a gathering like the World Economic Forum this week.

The task is to travel towards the light at the end of the tunnel. It will not be easy.

Related topics

- Published12 January 2024

- Published12 January 2024