Is Ireland's productivity boom real or 'artificial'?

- Published

Guinness produces 3.5 million pints of beer a day in Dublin

Behind the traffic of Dublin's Liberties, lies the sprawling factory site of one Ireland's most famous brands.

Guinness has brewed beer at its city factory since its founder, Arthur Guinness, took over a derelict building in 1759. Now, the "black stuff" is produced on a huge campus of buildings, connected up with metal piping, and accompanied by the clanging of metal kegs being transported by forklift trucks.

The operation, owned by global drinks giant Diageo, may appear far removed from Guinness' beginnings, but Aidan Crowe, operations director for beer, says the basics of brewing beer have not changed that much. "Our core process is actually very recognisable to the processes that Arthur Guinness would have used."

The Brew House at St James's Gate opened in 2013 and was the most efficient in the world at the time, Mr Crowe says. Currently, the Dublin brewery produces 3.5 million pints a day - that's 1.3 billion pints a year.

"Technology has allowed us to be dramatically more efficient, by making changes to how we manage things like cold water, steam usage, electricity usage, and so on," he says.

Mr Crowe says there are more improvements to go after.

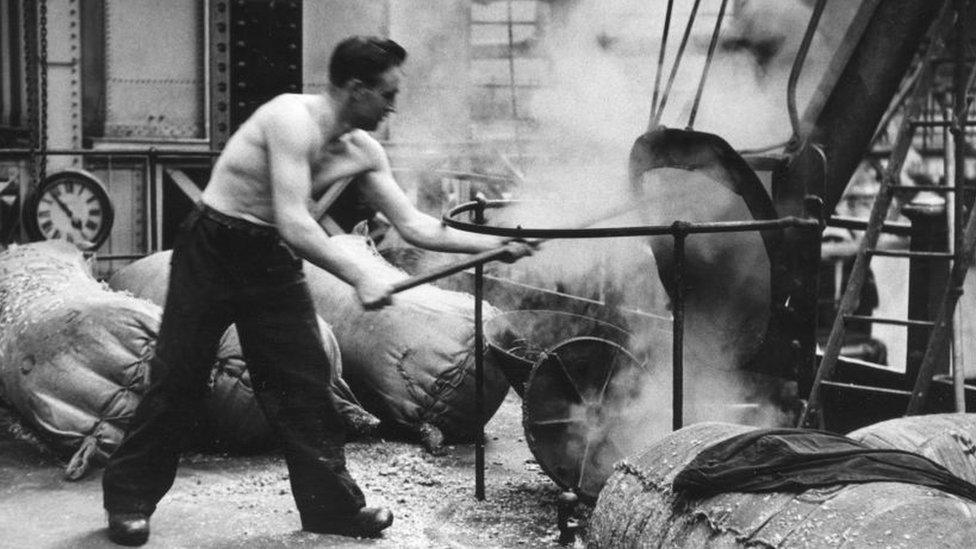

A worker at the Guinness brewery in Dublin clearing hops from a chute in 1953

"You set goals, maybe five-year, 10-year goals. But when you get to those milestones, you suddenly discover that the horizon has moved on."

With substantial resources, giant companies like Diageo can aim for that horizon. And it's not just Diageo - Ireland's economy has benefited from being the base for many multinational firms.

According to the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development, external rankings, Ireland is the most productive country in the world.

In economics, productivity is how much value a worker adds to the things they make or do, and some workers are in a position to add much more value than others.

For example, despite being busy all day, the productivity of someone behind the counter of a cafe is limited to how much people are willing to pay for the food and drinks they sell. Whereas someone at a technology or pharmaceuticals multinational is more likely to be working on high-value products and services - making them more productive in official figures.

Dr Emma Howard, economist at the Technological University of Dublin, says Ireland is a "unique" example globally, as the high concentration of multinational firms helps to boost productivity figures.

"If you look at our total labour productivity, it's two and a half times the EU average," she says. "But if you break that down into the domestic labour productivity, and the foreign sector productivity, there's big differences."

Dublin serves as a European base for several big tech firms including Google

Ireland's Central Statistics Office, measures productivity using gross value added (GVA) per worker, per hour. GVA is the total output of goods and services, minus input costs.

If you look at that figure it suggests that overseas firms are driving Ireland's productivity.

In the second quarter of last year the GVA of foreign firms in Ireland was €414 per worker, per hour. For domestic firms the figure was just €55.

The data also shows that in 2022 foreign firms made up 56% of the gross value added in the Irish economy.

Ireland is attractive to multinationals for a number of reasons including its low corporation tax rate, Dr Howard says.

"If you look at the types of firms that are here - Google, Microsoft, Pfizer, Meta - they're producing lots of very high value goods," she says.

"Some of those goods may be intellectual property, they're not physical goods. So some of those may be funnelled through Ireland to avail of those lower taxes."

But other economists argue that all those multinational firms are skewing Ireland's economic data.

"It looks like it generates a lot of economic activity, but the draw from that isn't that large. It's all artificial in a sense," says Stefan Gerlach, chief economist at Swiss bank EFG International and formerly a deputy governor of the Central Bank of Ireland.

He says it "cannot be the case" that the gulf in productivity between international and domestic companies is as wide as the figures show. "It's a measurement problem," he adds.

Mr Gerlach says using gross national income (GNI) may be a more accurate way to discuss productivity for Ireland.

That measurement better accounts for the way multinational companies direct the flow of income through their business.

In 2023, a paper from the Irish Fiscal Advisory Council, external said that using GNI as a measure may put Ireland's productivity more in line with its European peers.

Mr Gerlach says using a misleading measure of productivity could send governments in the wrong direction. "There is a risk that policy makers over-estimate the benefits and under-estimate the potential risks of having a large international cohort within the economy."

Dr Howard and Mr Gerlach say Ireland's attractiveness as a country to do business isn't all down to tax. Its position as an English-speaking member of the European Union is also a benefit. Plus, Ireland has a well-educated workforce.

"Across all age cohorts, we have a higher proportion of workers with a third level education than the EU average. We also have a much higher proportion of STEM [science, technology, engineering, and mathematics] graduates than our EU counterparts," says Dr Howard.

"So we've got these very skilled workers, in a highly educated workforce, and that's impacting our labour productivity."

Robin Blandford's firm is based in a former 19th century lighthouse

Whatever the data shows, productivity can often come down to the daily interaction of staff and management.

That's particularly the case since the pandemic, when many more workers started working from home. These days staff are less likely to be in the office, or might not even be in the same country.

This is a daily challenge for Robin Blandford.

His company, D4H, provides support to emergency response teams globally. It is based in a 19th century lighthouse at Howth head, overlooking Dublin Bay.

The goal for Mr Blandford is to motivate staff across seven countries. "Productivity to me is when we're all pulling in the same direction," Mr Blandford says.

"So really good communication, everybody understanding and over-communicating to people, understanding which way we're going, how to make a decision."

"As we've become distributed, what we've asked people to do is become part of their communities. Stop letting your workplace pick your friends," Mr Blandford adds.