Running blind: How do you run the London Marathon without sight?

- Published

'Blind Dave' celebrates running a marathon

The London Marathon is a riot of colour and food for the eyes with its stream of runners and city skyline, but what do you get from it if you're blind?

Preparation for the London Marathon takes months of dedication, long training runs which increase over time and sporting perseverance through the dead of winter.

But training has to be a little more organised and a lot more trusting for the 32 visually impaired runners and their guides taking part in this weekend's event.

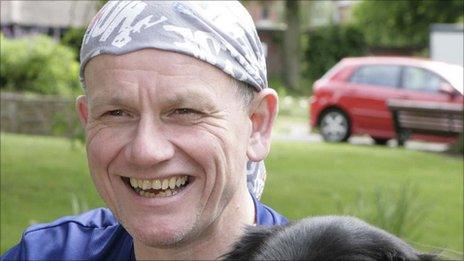

"I've had a series of guides because I wear them out," says Dave Heeley, 58, from West Bromwich who trades on the name "Blind Dave", and has run the London Marathon 14 times, using more than eight guides over the years.

"I love the marathon, it's fantastic," he says. "The camaraderie is incredible and the support around the course is wonderful."

Of the 38,000 runners 32 marathon participants will be visually impaired

He says the excitement begins when the participants collect their running numbers the days before the race and it continues to build as they travel to the starting line.

"And then the hooters go and it's just like heaven. You smell the barbecues, the beer, the ice creams, you hear different kind of bands, the bhangra drums and the pipes as well as people talking. The crowd are just unbelievable and it's electric."

But a long path has been trodden before the off.

Blind runner Rachel Mentiply explains how she and her sighted partner will run the marathon

Guide dogs are not permitted on the course, so all visually impaired runners need to find a partner who is happy to co-ordinate training and is not too caught up on getting a personal best themselves.

The team of two are held together by a strip of material - about 2ft in length - with loops on each end which go over the wrist and can be let out or reined in depending on the surrounding space. As well as responding to the direction the binding material is being pulled the guides also give verbal directions and mention any potential obstacles coming up.

Blind Dave says: "When we're in a tight crowd it's wrapped so our fists are together and our bodies move together, but when we get into an open space with room to manoeuvre we let it out so although I'm connected it's like I'm running on my own.

"We shout at each other and he pulls me left or right. We're always chatting and putting the world to right and sometimes we sing very, very badly."

Dave Heeley has also run the 156-mile Marathon Des Sables in the Sahara desert

He says in terms of choosing the right guide he opts for someone whose pace is slightly faster than his, but is confident with any decisions which have to be made quickly. He says that as a guide dog owner means he is used to being tugged in different directions.

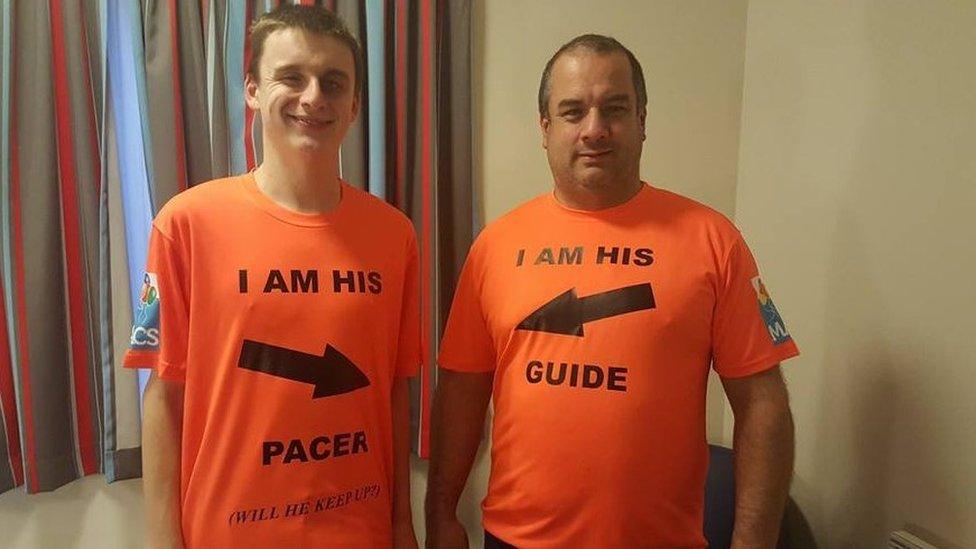

For Ben and Tim Lupton their partnership is being kept in the family.

Tim will be completing his seventh London Marathon, while guiding his 18-year-old son, Ben, around his first.

For Ben and Tim Lupton, it will be a battle of speed over experience in their first marathon together

Registered blind, Ben wears a prosthetic right eye due to Microphthalmia, where the eye is much smaller than normal, and he has very limited vision in his left eye. On a good day he can see the second line of a sight test, but he also has glaucoma, which affects his peripheral vision.

Although this is their first marathon together the father and son regularly go for off-road runs near their home in Exmouth, Devon, where they have become adept at dodging branches and jumping puddles.

"It astounds us what he can do," Tim says. "Ben loves trail running so we've got to watch out for low branches and veering left or right when I'm guiding him.

"I don't know what the roads are going to be like on the day in London and we don't know the obstacles but we shall take them as we find them and it keeps me thinking rather than just running it."

It is ideal if the pairings get on. But as with many parental relationships tempers can fray.

"There are a few arguments with him not listening and taking on board what I'm saying," says Tim. "When he's running with me he switches off but running with someone else he somehow manages to keep listening."

Ben, of course, disputes the claim, saying "We get on really well," adding that his dad makes a good running partner because he is slower - another challenge these runners have to overcome.

Ben says: "It's quite good when you're doing long distances because I have to slow down my pace so I won't go off too fast but I'm just looking forward to being out there and just knowing I can do it."

For Lupton Snr the thought of keeping up with his son is his biggest worry and, for the first time, he has had to put in speed work to keep up with Ben. "It can be very hard," he says. "This year's challenge will be whether I can keep going at his speed for 26 miles."

For male-female partnerships the difference in pace can be significant.

Lindsey Simmonds and Dan Wren train around south-west London

Lindsey Simmonds, 42, from Kingston, London, was inspired to become a guide runner after watching the Paralympics and getting bored with the traditional way of pounding the streets.

Working for United Response, a charity which supports those with learning disabilities, she was put in touch with one of its clients, Dan Wren, and the pair are in their final training sessions ahead of London.

Simmonds says: "It's a much more enjoyable experience running with somebody. When I'm solo all I'm thinking about is getting to the finish but this takes your mind off the running because you have to be much more aware of what's going on around you - the state of the pavements and the weather conditions - so it can be challenging too.

"The disadvantage is having to match someone else's pace. He's quicker than me, so he's had to adapt to my pace and I've had to try and speed up and that's been our biggest challenge."

Simmonds trains a couple of times a week in and around south-west London with Wren, who works as a gardener and teaches people with learning disabilities.

She says: "We tend to do the same route so he gets familiar with the noises and smells and I also have to plan routes that are suitable for two people to run alongside each other.

"His other senses are heightened and his hearing is amazing, so he'll experience the London Marathon through the sounds of the crowds."

She says the biggest challenges they faced as a duo are running at night and tackling uneven roads and pavements. There have also been mishaps along the way including getting lost during training sessions, which turns an hour-long run "easily into a two-hour run".

Reluctantly Blind Dave is not running the 2016 event as he shall instead be taking part in Escape From Alcatraz, a triathlon in San Francisco involving a 1.5-mile swim, an 18-mile bike ride and an eight-mile trail run. But he already has a place secured in the 2017 marathon and has advice for the runners.

"Just enjoy it. There will be lots of crowds and bumping shoulders so be prepared for that and just get into a rhythm and run your own race. Listen to your guide but remember to take in everything around you."

And his top tip for any runner - print your name on your t-shirt.

"Then people shout at you and you know that particular shout is aimed at you and that makes you feel a million dollars."

Follow the London Marathon on the BBC

You can follow the full coverage of the 2016 London Marathon and we will be featuring more inspirational stories from you in our live text commentary on Sunday.

Get involved: Send us your London Marathon stories and messages by using the hashtag #GetInspired on social media

Feeling inspired? There are events for all abilities so use this handy guide to find the best one for you.

- Attribution

- Published18 April 2016

- Attribution

- Published29 March 2016

- Attribution

- Published25 April 2016

- Published29 November 2011

- Published3 September 2010