Blind in the Arctic: A survivor's guide to living in Nunavut

- Published

It's only 200 miles south of the Arctic Circle and temperatures drop to below -40C.

In December the sun is in the sky for only four hours a day.

Welcome to Iqaluit. What's it like to live there if you're blind?

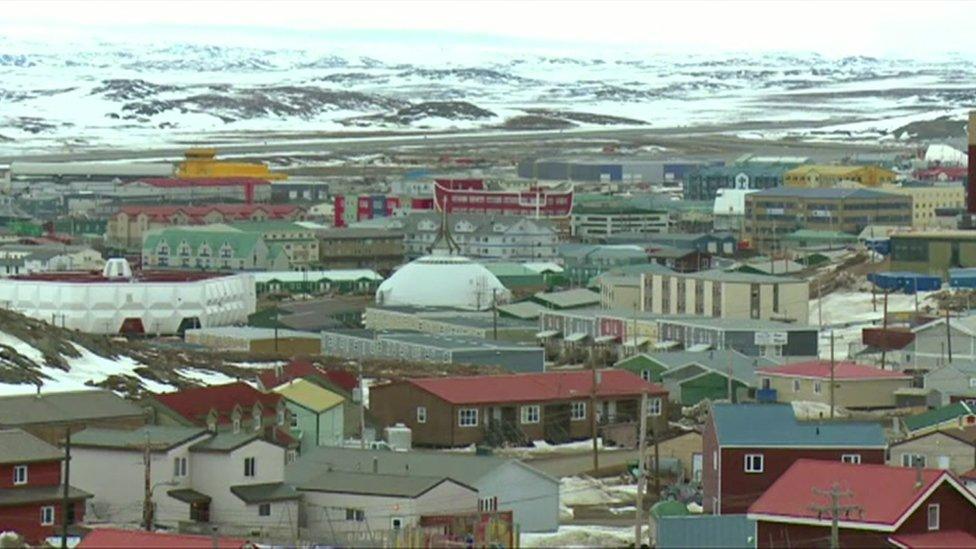

A colourful burst on an otherwise white landscape, Iqaluit in Canada is the capital city of Nunavut, with a population of only 10,000 souls.

"Sticking your head out there is like sticking your head into an extremely cold freezer," Mike Stopka told BBC Ouch from his heated city house.

Raised in Wisconsin in the US, he moved to Iqaluit in 2013 after meeting Jenna, now his wife. Both are visually impaired.

"I came to Canada to visit and never went home," Mike says. "I didn't even know Iqaluit existed until Jenna told me about it."

Nunavut is a region made up of 25 communities sprawled across more than two million square kilometres. The territory occupies a fifth of Canada's land mass.

Nunavut was only named a territory 16 years ago and is one of three alongside Northwest Territories and Yukon

It comes with very particular challenges for those without sight, but also offers good working opportunities and follows the Inuit ethos of inclusivity.

Jenna is almost completely blind. She has glaucoma and although she has some light perception in her right eye, she relies on her guide dog, Wendye, who wears a jacket underneath her harness and boots on her feet to brave Nunavut's freezing roads.

"She adjusted pretty well," Jenna says. "She's a tough cookie. She doesn't get too cold and she doesn't complain too much."

But even with Wendye, the lack of conventional city infrastructure throws up challenges.

"There are no sidewalks so it's sometimes hard to know where the road starts and the side of the road is supposed to be," Jenna says.

"It's dark and sometimes you get blinded by headlights so it's pretty tricky to navigate."

As well as the usual traffic there are skidoo riders to avoid. And the glare of the snow from the sun's reflection can be disorientating.

Carolyn Curtis, from the Nunavummi Disabilities Makinnasuqtit Society, describes Nunavut as "one of the most inaccessible communities in Canada". As well as snow and ice making it difficult for people with disabilities to get around, she says many building entrances are inaccessible.

As a newcomer, Mike found it hard to find his way around the city; businesses often convert houses into offices without putting lighted signage outside and the city operates a confusing house number system too. "Whatever sense it makes, 1425 is between 1412 and 1416," he says in bemusement.

The Iqaluit community shares the landscape with polar bears and geese, and is always at the mercy of the weather.

Living on the edge

Meet the disabled people living in the Canadian Arctic and the Australian outback on this BBC Ouch isolation special.

We talk with Mike and Jenna from Iqaluit and, in remote Australia, we speak to a man in Berrigan who set-up a "shed" for men to congregate and talk while they toil, in order to combat isolation and mental health problems.

Follow BBC Ouch on Twitter, external and Facebook, external, and subscribe to the weekly podcast.

There are no roads to Nunavut and the 25 communities are only connected for a few months each summer by boat. Foodstuffs and essentials are brought in by ship or plane. Sometimes, Mike says, the store aisles will be completely empty.

Its geography means that air travel is the most common mode of transport, but it's expensive. Flying from Iqaluit's airport, known locally as the Yellow Submarine because of its lurid colouring, to Ottawa three hours away costs £1,556 (2,578 Canadian dollars). A return flight to Montreal comes in at £2,032 (C$3367).

Many jobs in the city come with a salary boost known as the Northern Allowance, much like London Weighting in the UK.

It's a capital without the usual commercial landmarks too. There are no McDonald's or Wal-Marts on the streets and at supermarkets the choice of food can be slim and comes with a hefty price tag - £25 (C$42) for two chicken breasts for example.

Without wi-fi, the city relies on satellite internet which is unable to cope with streaming content from services such as Netflix. It means Iqaluit's DVD and CD market is booming.

Most residents in Iqaluit are of Inuit descent, while others have moved in for work such as scientific research or mining. Mike, who has low vision, works as a taxi dispatcher and Jenna, who is half-Inuit herself, works for the government's fishing licence department.

The city's medical services are also unique with many doctors rotating in and out for set periods of time and there is often a lack of diagnostic or procedural equipment available.

It means for anything which can't be treated on site, the patient is flown out of the territory.

The relative lack of medical services goes hand-in-hand with another quirk of the region. While the native language - Inuktitut - has many words to describe snow, there is not a single word for "disability".

Mike says: "I was told by one of the Inuit elders it's because the Inuit don't believe in titles."

For a community without such a word, he says, it responds very well to people who need support. The local government has always been quick to respond to his requests to remove snow from walkways.

But it comes with a double-edged sword. Not all Nunavummiut want to identify as disabled which can mean they miss out on support. It's an issue which Mike is hoping to address.

"I'd like to see more services offered in a less formal and bureaucratic way," he says. "I find the bureaucracy really prevents people from coming forward and getting what they need.

"I'd love to see us get funding for sidewalks and get good, marked, crosswalks, not just signs on wooden posts - as parts of town are completely dark with no lights."

He is also hoping to secure Braille signage and create more community groups.

But like anywhere in the world it all comes down to cost.

Despite the challenges there are many positives to moving to this most isolated of capitals if you are disabled.

"If you are willing to make adjustments, it's a prime place to get jobs," Mike says. "Especially if you are willing to learn about culture and stay here.

"If a disabled person is work-ready, the Government bends over backwards."

Nunavut's youth, much like it's landscape, also offers a blank slate rich with possibilities.

Carolyn says: "We're a new territory and there aren't a lot of services, but that can also be an opportunity for the community to really come together and not just rely on the government to provide services, but to really make things happen themselves.

"The very principles of Inuit culture are very much about inclusion."

- Published14 June 2012

- Published8 January