The scuba dive that crushed my spine

- Published

It had been planned - a deep dive for four experienced scuba diving instructors. But halfway through the session, two compressed air tanks ran out, setting off a catastrophic chain of events.

The sky was blue over Cyprus. It was a rare day off for friends Rich, Paul, Emily and Andy and they decided to take advantage of the crystal blue water and search for nudibranchs, a type of sea slug.

They launched a boat from the shore, anchored it and dived into the sea one-by-one, using their fins to propel themselves downwards into the deeper, darker, water.

They carried on to depth of 40m - 10m deeper than the instructors would take their clients.

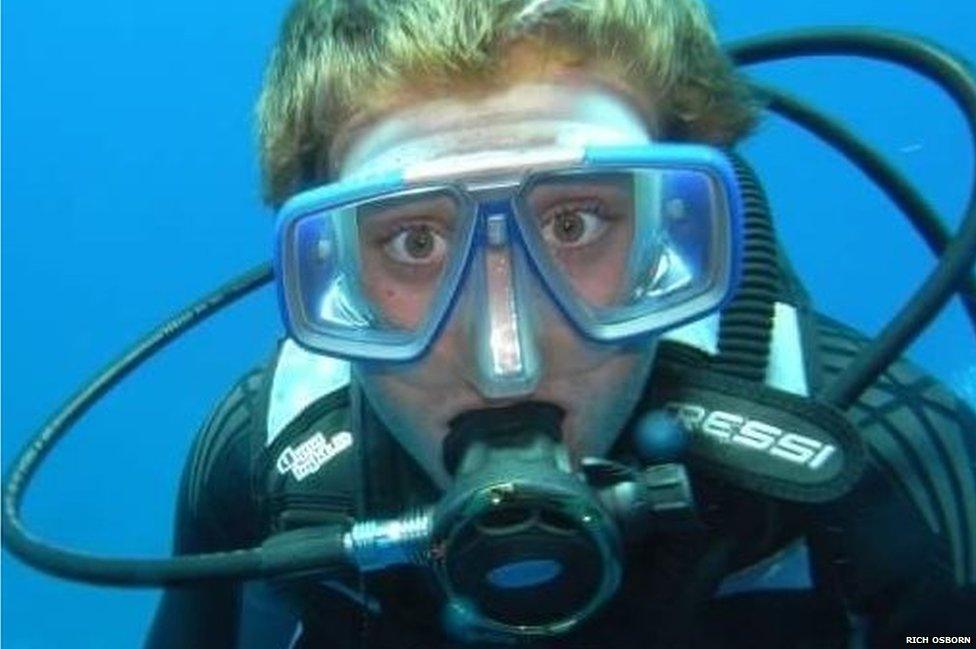

They were young and wanted to "push the limits", Rich Osborn, then 21, admits. But they were experienced and well-practised at this level.

As they started to explore their surroundings, two of the group unexpectedly signalled to the others that their tanks had run dry.

Osborn felt "absolute surprise" at this turn of event. But they were trained for such eventualities. There was no need to panic.

The divers used hand signals and underwater slates and pencils to write notes and arranged to share the remaining two tanks of air "breath for breath" as they ascended to the surface.

The quartet started to rise slowly, but at 30m, cold dread swept through them.

They had all run out of air.

"We were frantically trying to sign to one another, scribbling down notes, thoughts and plans. From there you get a little bit panicked - a mix of fear and the unknown."

The group had a decision to make - drown, or rocket to the surface and risk decompression sickness.

"We took one last breath," says Osborn.

Listen to the podcast: 'Do we drown or rocket to the surface?'

Rich Osborn thought he had the perfect summer job as a scuba diving instructor in Cyprus.

A full transcript is available here. For more Disability News, follow BBC Ouch on Twitter, external and Facebook, external, and subscribe to the weekly podcast.

Osborn had grown up in Edinburgh. He was outdoorsy and into mountain biking and hiking. He took up scuba diving at the age of 14, and by the time he was 18 he was a qualified instructor.

As a university engineering student, he would spend his holidays working with a diving company just outside Ayia Napa in Cyprus.

He taught classes and took groups of certified divers to see local reefs and shipwrecks.

"I had friends there. It was quite a nice lifestyle, sunny every day," he says.

The town was "picture-postcard" - fantastic beaches, dramatic cliff faces - with a "chilled vibe". He was "living the dream". It all changed on 23 August 2009.

As Osborn took his final breath, the mouthpiece felt tight around his mouth. It was a sure sign there was nothing left in the tank.

The group needed to ascend as "quickly as humanly possible" but in a controlled, slow, manner to minimise the risk of decompression sickness - also known as the bends - and remember to exhale continually so as not to stretch their lungs.

"Everything in your body is screaming to get to the surface so you can breathe," he says.

"It's an internal battle. We tried to slow it as much as possible, but some people had the fear kick in and they were trying to go a little bit faster than we would like."

They shot to the surface more quickly than planned, desperate for air. "It all went very, very fast," Osborn says. "But I knew near enough instantly what had happened."

As he surfaced, his back started to tighten. From there he started to vomit and his coordination went.

"With the sky being blue and the sea being blue, I was disoriented and rolling around and trying to get some breath."

The group started to swim back to shore, but Osborn's legs slowed and eventually stopped.

He was helped out of the water by some other divers and taken to a hyperbaric, or recompression, chamber on the island. Time was of the essence, but it was a four-hour drive away.

"By that time, the damage was done," Osborn says.

He was sealed into the chamber, which mimicked the pressure he had felt 30m under water. The pressure was slowly reduced while pure oxygen was administered to recalibrate his body.

Under water, the nitrogen in the air we breathe has difficulty leaving the body and bubbles build up due to the pressure.

If the diver returns to the surface too quickly, the pressure is rapidly lessened but the bubbles don't have time to dissipate.

It's like opening a fizzy drink. Shake it up and open it slowly and the bubbles fizz safely out. Open it fast and the bubbles explode uncontrollably.

When this happens in the body, it blocks blood flow, stretches and tears blood vessels and nerves, and gets trapped in joints such as elbows.

The consequences vary from itchy skin to paralysis or death.

Osborn spent six hours a day, for a week, in the recompression chamber to dissolve the trapped bubbles before he was flown to Glasgow's spinal unit for further tests and MRI scans.

"All the doctors got together, looked at the evidence, and then it was relayed to me that there wouldn't be any prospect of walking again," he says.

"The nitrogen bubbles got caught in my spinal column, and as I came up to the surface they expanded and crushed my spinal cord."

Osborn was told his injury was "T4 incomplete" the four referring to his fourth vertebrae in the thoracic part of his spine. "Incomplete" means that he has some motor and sensory function - he can flex his right ankle and is able to feel some sensation.

"I can't walk at all. I'm in a wheelchair all the time," he says. "I'm a paraplegic, which means I still have arm function, but leg function is gone and some internal organs have a bit of paralysis."

About 40,000 people are affected by spinal cord injury in the UK, which is a permanent condition.

"This is the new normal and you just embrace it. You take what life throws at you and then you put a positive spin on it," says Osborn.

He spent time at a rehabilitation unit and admits there were "moments when it was frustrating".

"One thing would seem to lead onto another thing and it would just be an awful day," he says.

"I'm very good at compartmentalising stuff, so I just maybe cry it out, go to sleep and then wake up the next day and it's a new day and then you just go from there."

Of the four divers that day, Paul and Emily suffered no adverse effects, while Andy had problems with one of his arms. He also spent some time in the chamber to repair the damage.

The quartet remain in contact and say a bond formed between them because of what they went through.

They now know that what happened was "a disparity between what was planned in terms of breathing rates and what actually happened on the dive".

It was unpredictable.

Rich Osborn from Edinburgh has taken part in a charity climb of Snowdon, with 14 other teams.

The life-changing injury did not put Osborn off outdoor pursuits. In fact, he turned to them to build his strength and continue his rehabilitation.

He got involved in swimming, basketball and hand cycling. Twelve months after the accident he returned to scuba diving and now teaches other disabled divers.

Earlier this summer, now aged 30, he took on the Snowdon Push Challenge where teams climb Snowdon - the highest mountain in Wales - with one team member in a wheelchair.

Osborn's team completed the challenge in just over seven hours and raised £5,200 for the spinal injury charity Back Up, which had taught him skills such as how to tackle kerbs and ramps.

But it meant more than that.

"I got that feeling back of a sense of achievement and being at one with the elements again," he says.

For more Disability News, follow on Twitter, external and Facebook, external, and subscribe to the weekly podcast.

Related topics

- Published2 February 2013