'The 80s song that brought my lost memory back after 10 years'

- Published

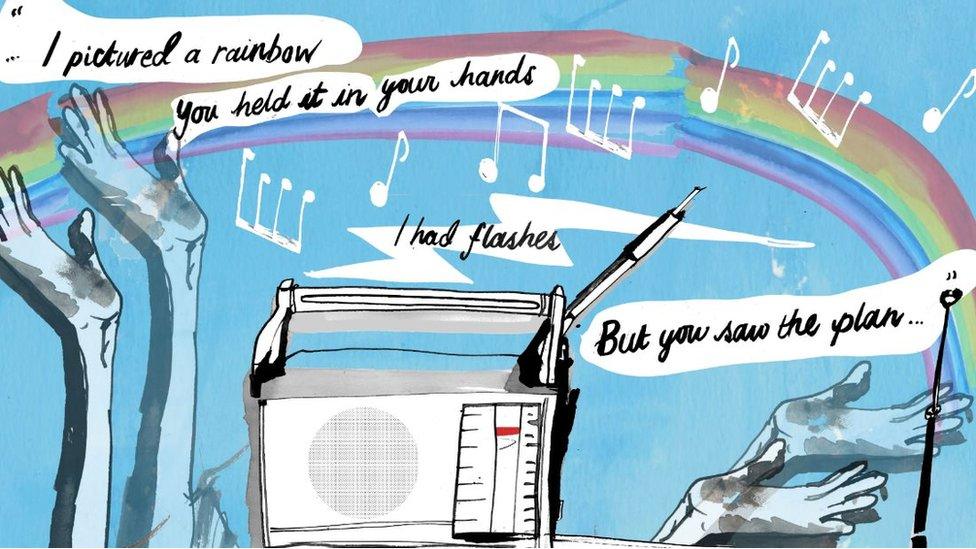

A drumbeat comes in, then the keyboard. A sequence of notes marches towards the singer.

"I pictured a rainbow

You held it in your hands

I had flashes

But you saw the plan"

The music reached somewhere deep in Thomas's brain.

And as the lyrics of The Waterboys' 1980s hit, The Whole of the Moon, came through Thomas's earphones, he experienced six flashbacks - each triggered by the one before.

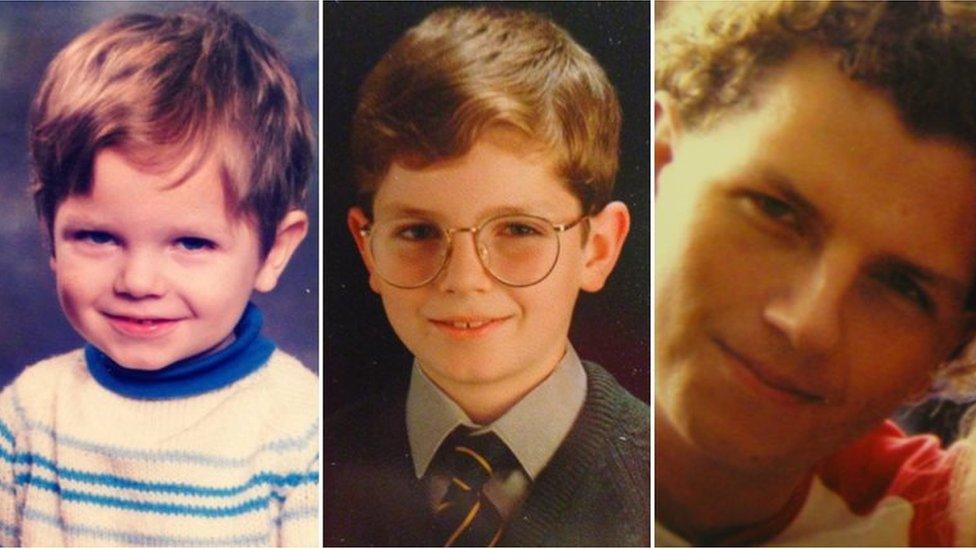

For the 30-year-old, this was an extraordinary moment. One he had craved for 10 long years - ever since his entire memory had been wiped when he was hit by a car. "It was the most magical thing ever," he says of the memory-chain.

"I was sitting on this weird blue floor and I could see this silver radio. Then, I was in another place and I was holding this man's giant hand… and then there was another memory."

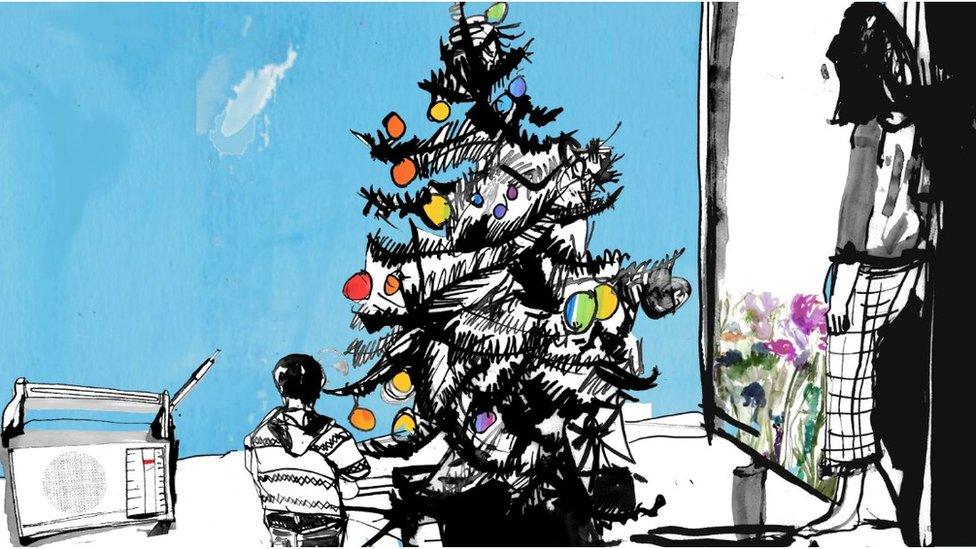

He recalled a Christmas tree, towering over him. "There was a woman standing, and she was young and she was smiling and she didn't have grey hair. It was my mum and I was her little boy. And it was real."

Thomas immediately wrote the memories down.

He needed to be sure they were real, and it wasn't his brain playing tricks on him. Could it simply be another manifestation of his brain injury, like the personality change and face-blindness he had contended with?

But if the flashbacks were real, how had his brain, finally, managed to unlock his memory?

It was evening and still busy in central London when Thomas Leeds headed to Green Park station to pick up a lift from his father. The 19-year-old was on a gap year before starting university and had been to meet a friend.

At 21:00 GMT, he crossed the road and was hit by a car.

The officer who witnessed the accident was visibly traumatised when he later recounted what had happened.

Thomas had been thrown over the roof of the taxi and landed on his head. The front of the vehicle had been dented, the bonnet wrecked, the windscreen smashed and the roof concaved by the impact of his body.

Thomas's father, Dr Anthony Leeds, rushed to St Thomas' Hospital after the police called telling him there had been an accident.

But Thomas, it seemed, had been extraordinarily lucky and escaped with a minor head injury. "There was very little evidence of injury other than scratches and bruises," Anthony remembers. The next morning, Thomas was discharged from hospital.

Over the next couple of days Thomas complained of nausea, a terrible headache and back pain. When the police officer phoned for an update he was shocked to learn Thomas had been discharged. This unsettled Thomas's mother, Jacqueline. "The officer's feeling was no-one could walk away from that," she says.

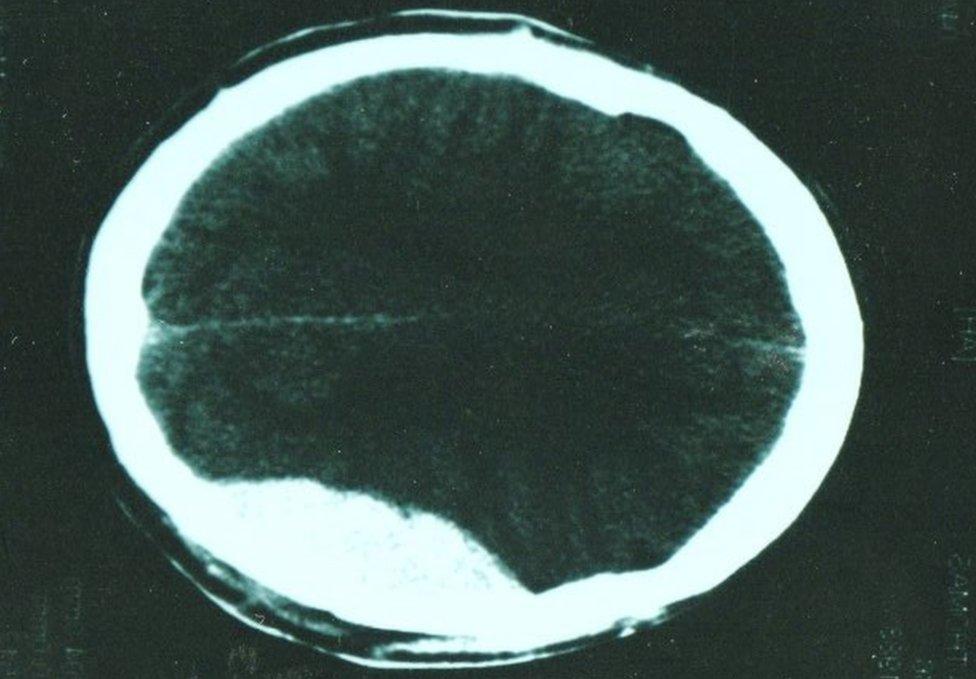

After hearing this, she took Thomas to A&E and demanded a scan. It revealed the "utterly shocking" truth - a blood clot had formed in his brain.

"He was 24 hours away from death," Anthony says.

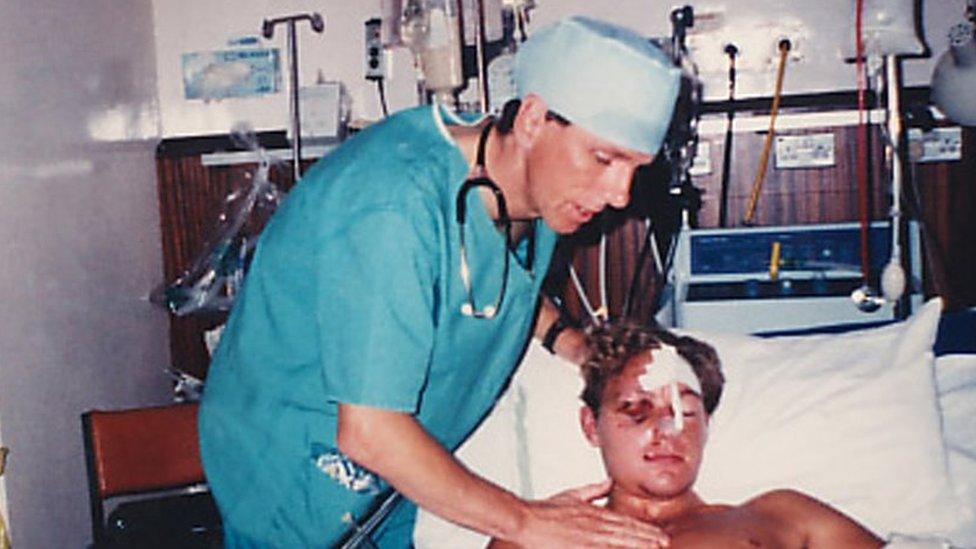

Thomas underwent surgery to remove the clot. And when he came around in the intensive care unit, he was said to be docile.

"I have vague memories of being very confused, but oddly enough I wasn't afraid. I didn't know to be afraid," he says. "I was like a baby."

He describes being in an "emotional bubble" - something brain injury charity Headway says is common after a head trauma because of the chemical imbalance caused. It can leave the patient feeling, surprisingly, content.

Thomas enjoyed seeing the people who came to visit him as he recovered. Though they seemed familiar, when they told him they were his parents and his five siblings, he couldn't recall them.

Everyone put this early confusion down to the effects of the morphine.

"He walked and talked and that to us was fine," Jacqueline says. "That's the most we could have hoped for, so we didn't go probing. We all assumed Thomas was okay."

But when he returned home, Thomas didn't remember the house - even though he'd lived there since childhood.

People tried to jog his memory about what he had been doing in the months before the crash by mentioning friends and the interests he had.

"I really tried to fit in with everybody when they told me these stories," he says, but he remembered nothing.

Realisation slowly dawned on the family - Thomas had lost all of his pre-crash memories.

Initially this didn't faze him. The first few years drifted past as he recovered from three back fractures also sustained in the accident. He says the "emotional bubble" continued to cocoon him.

"I suppose it's how most people remember their childhood summers. Everything was wonderful, so big and unlimited, and I sort of remember - it sounds so silly - just sitting in the park under trees."

Thomas was fortunate because, although he couldn't remember his school days, he had retained basic levels of reading, writing and maths. What had gone was his cultural knowledge and references - the things at the heart of conversations and relationships.

And while he was able to make new memories, his personality had changed, too. This is something a traumatic brain injury can do. Previously, he'd been cooler and more reserved, but now he was affectionate and excitable.

"My brother wasn't glad that I'd had this accident but he was like, 'You're much nicer'," Thomas jokes. His mum Jacqueline noticed it too. "He is very emotional. He's very open. There's something of the child that isn't in the others."

As Thomas recovered he began to wonder about his future.

He thought about the university place he'd been due to take up before the crash. He had planned to study design, but when he looked at his drawings they no longer interested him.

"That boy that I was, just feels no more real than an ancestor. You know they existed and maybe you've seen pictures but they don't feel real," he says. "The first few years it didn't bother me. We were all so young so everything was about 'tomorrow'. But as our 20s ticked by, everything became about 'yesterday'."

Thomas's future had stalled. Meanwhile, his siblings and friends were now in their mid-20s and had moved on with careers, houses and children.

"I still felt very lucky to have all that I did and just be alive, but having to face the hard facts of the future without a beginning started to feel really unfair."

And there was something else missing in his life too - love.

Internet dating was starting to get a better reputation by 2010, so Thomas signed up. He met a few girls but nothing came of it. Christmas was approaching when he arranged to meet Sophie. She was also a Londoner, and also had five siblings.

After telling her about his unique situation, they met for dinner and went for a wander through the West End. They hit it off and planned to meet the next day. As they parted, Thomas said: "I'm sorry, but I won't recognise you tomorrow."

There was another complication from the crash. Thomas had developed prosopagnosia - face blindness. It meant he couldn't recognise anyone out of context, not even his parents, let alone a girl he had just met.

With face blindness, the brain is unable to recognise the variations in faces - the arch of an eyebrow, the angle of a tooth, all of which help us identify people.

Many of the 1.5 million people in the UK who have it are born with it, but Thomas's accident had damaged a small area at the back of his brain responsible for vision, recognition and co-ordination.

He learned strategies to recognise people using location, context and dropping pins in mobile phone maps, and he can place someone on hearing their voice. But there was something different about Sophie. "The week before we met, she'd dyed her hair bright red, that sort of crazy red. She was like a beacon."

For the first time in years, Thomas was able to recognise someone in a crowd, and their love story began.

They dated and two years later they married. Soon after, one daughter came along, then another. Sophie never stopped dying her hair and is still the only person Thomas can recognise.

"She's amazing. She always makes me feel that she's lucky to have me. It made me feel a lot better about the future."

Ten years on from the accident, although Thomas had re-visited locations from his past and interrogated family and friends, none of his memories had returned.

And then came the remarkable breakthrough. Thomas had curated an '80s playlist for his 30th birthday - music he, apparently, grew up with. The night before his party, he went to bed and put his earphones in. He listened to the playlist track-by-track and knew all the songs by heart.

He pressed skip one more time. Somehow, the track The Whole of the Moon, which peaked at number 3 in the UK charts, located Thomas's past.

"It really changed everything for me," he says of the series of flashbacks.

"It was so short, nothing was said, but knowing that it was real and I've got it in my head and it's not just a story, and it's not just a grainy photograph ... it was a little bit of my beginning."

To explain the science behind the flashbacks, neurologist Dr Colin Shieff says memories are made up of "packets of chemicals" involving various dimensions including smell, taste and touch.

"It just needs little memory chemicals floating around to trigger a slightly bigger picture," he says. "That causes a cascade that he translated into a vision." After years of miss-firing, the packets of chemicals in Thomas's brain had collided and unearthed memory.

So were they always there?

Dr Shieff says Thomas's long-term memory is probably still there but remains out of reach in an "absolutely terrible filing system".

"You can have a manuscript of a book, and when you read it it's wonderful. But if you drop those sheets and someone picks it up, then they're faced with pages with lots of content that doesn't follow. Some of the pages have got a bit screwed up and crumpled."

A second burst of memories happened years later when Thomas came across The Snowman on YouTube while he was trying to learn about the childhood references he had lost. The unique images and soundtrack triggered another memory - lunchtime in the school canteen.

"It was enough to make me feel like I have an education," he says.

Dr Shieff says "recovery can continue indefinitely", so there is scope for Thomas to unearth more memories but no certainty.

As a stay-at-home Dad to his two young daughters, Thomas says "some days are better than others", but little things like running around the park after his children can be difficult because face blindness makes it harder for him to recognise them.

He says the "empty years" sometimes get him down, but his daughters play in the same parks he once did, and he is creating new memories with them.

Another legacy of the crash is epilepsy, and on "bad head days" he can't leave the house.

"The scar tissue of my brain interferes with the signals and is what causes me to have seizures. And that seems to be affecting my memory more and more.

"Knowing I might lose control of my consciousness can be quite terrifying."

After a tonic-clonic seizure - where he loses consciousness - he temporarily loses about 10 years of memory. The last time it happened, he came round thinking it was 2008.

"I didn't know who my wife was, didn't know who the kids were. Sophie showed me the Amazon Echo smart speaker and it blew my mind." He sees the humour in it now, and the family writes down these funny episodes so they're there in black and white for Thomas to remember. Always.

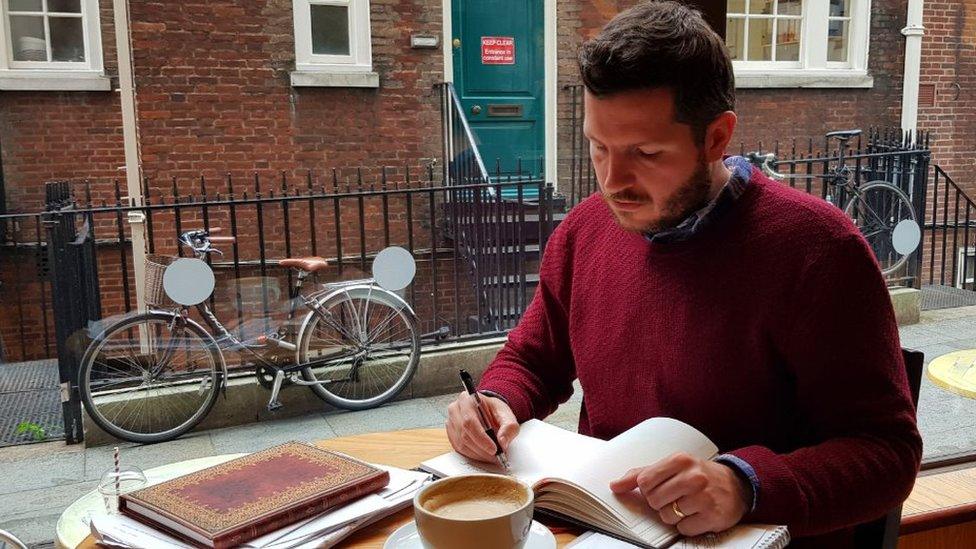

He's also become passionate about creative writing, an interest he apparently shares with his childhood self, and has written a fantasy-adventure for 8-to-12-year-olds.

His protagonist, Jayben, has epilepsy and wakes up with no memory in a world of elves - he's a hero being hunted and must recover his memory before he is found.

He preferred writing a children's book rather than a memoir because this way he wouldn't be reliving his own story. He says it is therapeutic to turn the pain and difficulty into "something new and exciting".

The book is the first in a series and has been signed by The Good Literary Agency. Thomas says he's excited about the next chapter in his life. And while his writing moves forward, he is still trying to piece together his history.

"It's been 18 years now and I am this person. It's lovely knowing a little bit of who I was before, but I've had such a life now." And he still treasures that flashback of his Mum at Christmas.

"Just knowing that I've got something real from before, from the beginning of my story, really helps me face the future."

You can keep up to date with Thomas on Twitter: @thomasleeds, external

Illustrations by Katie Horwich

- Published22 July 2017