Mental health and pregnancy: 'I couldn't hold my baby for more than a minute'

- Published

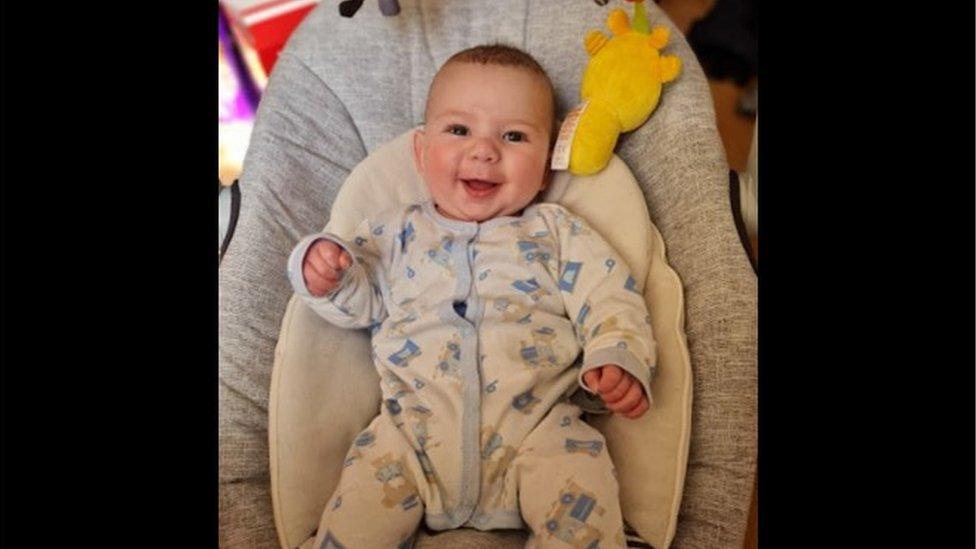

Seaneen Molloy was excited to discover she was expecting her second baby during lockdown. With a history of mental illness, she carefully planned the pregnancy, but when her baby arrived she experienced the "terrifyingly rapid" onset of a crisis which left her unable to hold baby Jack.

Having a baby is supposed to be a joyful experience, and for lots of women it is. However, up to 20% experience mental ill health during pregnancy and the year after birth. Tragically, suicide is the leading cause of death in new mothers.

Women who already have a mental illness are at a high risk of relapse during pregnancy - that's women like me.

I have a diagnosis of bipolar disorder and an anxiety disorder. This meant that pretty much from the moment I became pregnant, the perinatal mental health team were involved.

This includes specialist midwives, psychiatrists, nurses and social workers whose goal is to support women to stay well, and intervene quickly if they don't.

Normally, I manage my mental health by being careful with my sleep and leading a pretty boring life away from overwork and alcohol, but pregnancy chucks in a host of factors you have no control over.

Hormones rage through your body, wreaking havoc upon your mood, your energy levels and your ability to keep your lunch down. You either can't stay awake or are awake for hours - peeing a thousand times and being hoofed by tiny feet.

I had managed to stay well, and off medication, for years, but in the run-up to birth antipsychotic medication was introduced to prevent postpartum psychosis. This can cause women to develop delusions and lose touch with reality.

It's the one I was most at risk of developing due to my history of bipolar disorder, but in the end, I experienced postnatal anxiety.

My mental health had been largely OK during my pregnancy and my labour and after-care were carefully planned.

I had a calm elective Caesarean section due to a traumatic first birth, a room of my own and the baby was whisked away on his inaugural night so that I could get some all-important sleep (this bit was hard - it went against every natural instinct). A procession of midwives, doctors and social workers visited to see how I was doing.

Although I found it intrusive, it helped me feel safe. When I was discharged from hospital with my baby, Jack, I felt swaddled in care and confident everything would be OK.

It was a complete shock that I did get ill.

In the chaos of newborn-life I forgot a dose of my anti-clotting medication which is given to mothers after C-sections.

And this one tiny event broke my brain.

I went from mildly chiding the home treatment team for their postnatal visits, because I was fine, to a full-blown mental health crisis within about 12 hours. It was terrifyingly rapid - which is why perinatal mental illness can be so deadly.

My mild anxiety exploded into an all-consuming panic that I was going to die imminently from a blood clot in my lung. I couldn't think of anything else but the black terror of certain death that was coming for me - how I was going to leave my children, how I'd brought a new child into the world never to know me.

I called out-of-hours GPs describing symptoms I was convinced I had, sobbed, screamed and couldn't breathe. I terrified my husband and myself.

Then we hit the emergency button.

The psychiatrist came over with the home treatment team. They took my fears seriously, which I appreciated, and gave me a physical examination and the missed dose of medication. My antipsychotic medication was increased to the maximum dose and benzodiazepines - a type of sedative - prescribed, to try and calm me down.

I wasn't allowed to be left alone and the mental health team were to visit me every day where I tried to articulate my terror to their masked faces.

At first I resented their visits, but they became a 30-minute space where I could let down the exhausting facade and share how I was really feeling.

My anxiety then transformed into an obsession that Jack was going to die. I was afraid to leave the room and rested my hand on his chest all night.

If my husband took him out to the shops with his brother, I cried and paced about, imagining they had all been hit by a car. I texted him incessantly.

Everyone was saying I needed "rest", so he tried to give me space. But after the second or third breakdown, he agreed to keep his phone on loud and to answer quickly. The home treatment team also advised he give me clear timescales so I knew when to expect them home.

Listen to the podcast: A postnatal mental health crisis left Seaneen feeling ‘robbed’.

But the medication also caused intense restlessness. I couldn't sit still. I couldn't get comfortable enough to hold my baby for more than a minute.

It caused parkinsonism, a side-effect of antipsychotics which affects muscles. It meant my face was a mask - I couldn't smile and make silly faces at my baby. I walked with a shuffle, purposelessly, until I went to bed, exhausted.

I insisted on doing the night feeds as it was the only thing I could do as a mother, even though sleep was essential to my mental health.

And all this was happening through lockdown when family and friends couldn't come and help.

Gradually, with additional medication to lessen the side effects and support from the mental health team, I started to feel better.

I began to have other thoughts than of Jack dying. I started to recover physically which meant I could shuffle outside with the pram and with the psychiatrist's blessing, I began to lower my antipsychotic medication, and the side effects disappeared.

Finally, I could hold my baby and begin to bond with him. When he smiled at eight weeks, I smiled back at him.

I'm not entirely recovered and am still with the perinatal mental health team and on medication. My anxiety is still there - sometimes it's just background noise, other times it's cacophonous.

I don't have many strong memories of the first two months of Jack's life, but I'm still doing the night feeds - some nights I still lie awake watching Jack breathe, other nights, I manage to sleep.

Despite my experience, I feel fortunate - there's currently only one perinatal mental health team in the whole of Northern Ireland, and it's in Belfast, where I live.

If I hadn't had that team, I wouldn't have known where to turn. My mental health would have got worse, and I would have ended up being hospitalised and separated from my baby. I wouldn't have had the immediate and understanding treatment and support that I had.

Thanks to local campaigning, new perinatal teams are being developed across Northern Ireland. And finally, more women like me won't have to struggle alone.

Seaneen Molloy works for a mental health charity and also co-presents Mentally Interesting, a podcast by BBC Ouch which you can subscribe to on BBC Sounds. The next episode is about travel.

If you need any advice about mental health and pregnancy, the NHS has a dedicated page, external containing tips and guidance, or you can contact charities including Maternal Mental Health Alliance, external, Pandas, external or Action on Postpartum Psychosis, external.

For more disability news, follow BBC Ouch on Twitter, external and Facebook, external.

Related topics

- Published6 April 2021

- Published26 October 2020