Ukraine orphanages: Children tied up and men in cots

- Published

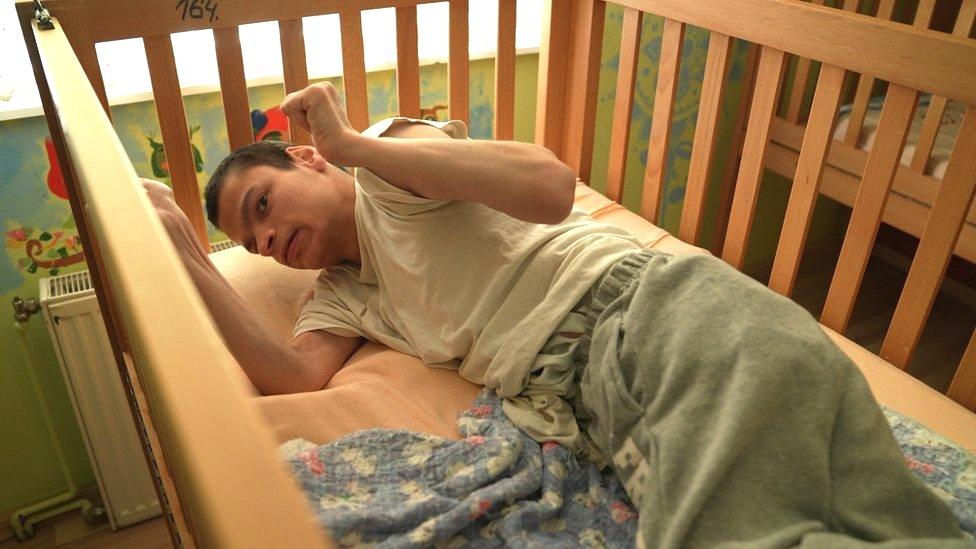

Vasyl, who was sent to an institution when he was five years old, has been tied to this bench for hours

Vasyl Velychko has been tied to a bench on a baking hot day for hours, but no-one hearing his screams will untie him.

The 18-year-old is one of thousands of disabled people living in Ukraine's orphanages. BBC News has gained access to five institutions and found widespread abuse and mistreatment - including teenagers restrained and adults left lying in cots for years.

Human rights investigators say Ukraine should not join the European Union until it closes these institutions.

Before the war with Russia, the Ukrainian government said it would reform the system.

Readers may find some details and images in this report distressing.

Vasyl, who has epilepsy and learning disabilities, lives in an orphanage on the outskirts of the city of Chernivtsi in south-west Ukraine.

The teenager is wearing a nappy. He rocks back and forth, intermittently giving out a long high-pitched scream, but the staff don't react.

They are tired, overworked and it is clear that it is easier - and accepted - to keep an eye on the children and young people by restraining them.

An influx of evacuees from the east has put further pressure on the system, but the ways people like Vasyl are treated in Ukraine's institutions long pre-date the Russian invasion.

Locked Away: Ukraine's Stolen Lives

A BBC News investigation exposes the abuse and neglect of disabled people locked away in institutions across Ukraine.

Watch Now on BBC iPlayer(UK Only)

Next to Vasyl lies another young man. His hands are bound together with the sleeves of his jumper. His vacant eyes stare into the distance and a pool of urine has collected beneath him.

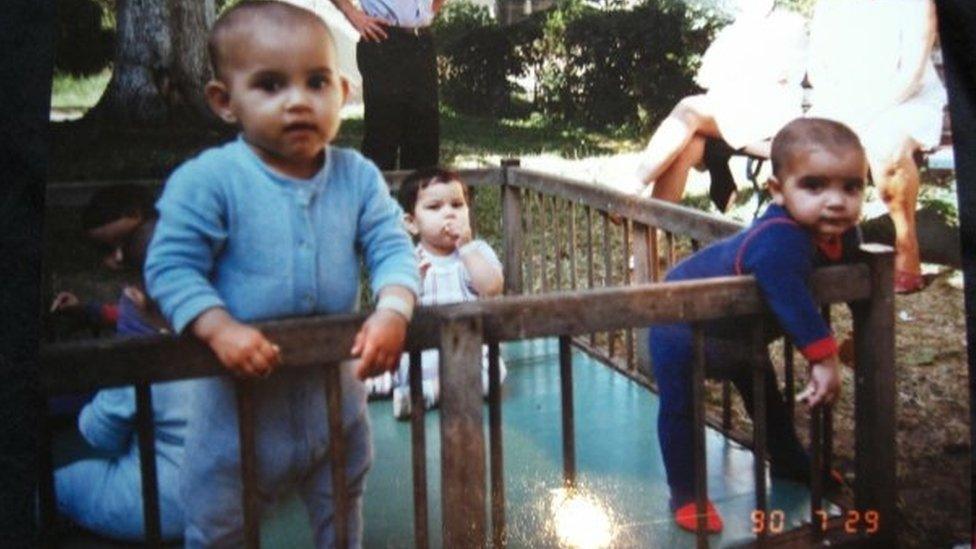

These disabled boys are among 100,000 children and young people who live in Ukrainian orphanages - but many of them aren't even orphans.

The majority have families but end up living in these places due to a lack of community services and support.

Vasyl's family felt they had no choice but to give him up.

They had tried to get a diagnosis when he was very young - even consulting a neurosurgeon from the UK - to help him get the support he needed.

But a poor health and social care system meant they struggled to provide for him at home, as he has regular seizures and can become aggressive.

In the end, when he was five years old, the local authorities told them an institution was the best place for him.

"It's very hard to be a parent of a disabled child," Vasyl's mum, Maryna says as she gently holds her son's hand. She doesn't question or seem perturbed by Vasyl being tied down.

"A parent's heart is always with their child," says mum Maryna - pictured with Vasyl and his dad, Illya

"I am proud to be a Ukrainian, but we do need to have more support from the state.

"If we lived in the UK our son would probably live with us."

She says the first few years of visiting Vasyl were difficult - "we would come home in tears" - but they have now learned to live with the situation.

Ukraine has the largest number of children living in institutions in Europe.

They are casualties of a Soviet-era system that made the process easy for parents to give their child up to the state.

There was, and still is, a belief by many in Ukrainian society that disabled children receive better care in an institution.

Neighbouring Romania has closed many of its orphanages since children were discovered living in appalling conditions in the aftermath of the 1989 revolution.

But in Ukraine, before the Russian invasion in February, an estimated 250 children a day were being signed up to a life in an institution.

The network of nearly 700 facilities receives more than £100m a year from the state and employs 68,000 staff.

BBC footage reveals abuse of disabled Ukrainians

The Ukrainian government has promised a series of reforms over the past few years, acknowledging that its system of institutionalisation needs to change.

Until the war led plans to grind to a halt, the government had begun moving thousands of "orphans" into family-style group homes. But disabled people are excluded from these plans.

The Ukrainian government did not respond to a request for further comment.

Eric Rosenthal, CEO of human rights group Disability Rights International (DRI), says disabled people are now commodities in "factories of disability".

He has visited hundreds of these facilities and says he is always shocked and devastated by what he finds.

We are shown around another institution, about an hour's drive from Vasyl's orphanage, where disabled men in their 20s and 30s live in children's cots.

A man in his 30s whose limbs have twisted because of his life in a cot

They rarely leave these cots, even to eat - staff spoon-feed them through the bars.

Eric says one man's bony, warped ankles, and a young boy's protruding ribs, are a sign of "malnutrition over a lifetime".

He says the war cannot be used as an excuse for such appalling care, as disabled people have been neglected for decades.

Standing by the man, Eric says: "He is dying a slow death in this bed."

This boy's protruding ribs show malnourishment

The wooden beds are lined up next to each other, row after row. The brightly painted walls jar with the bleakness of these young men's lives.

They don't try to break free - they are just desperate for some attention.

In the next room, Oleh has been lying in bed for decades. The 43-year-old was sent to this institution as a young child.

Oleh is even fed lying down in his bed

He has cerebral palsy, a condition which affects movement and co-ordination. With the right care, people with cerebral palsy are able to live full and independent lives.

Oleh understands everything about the world around him - and his face lights up when he sees Halyna Kurylo, one of the investigators from DRI.

He recognises her from her last visit, seven years ago.

Oleh greets her with a warm smile and she introduces us. He expresses surprise and excitement when he finds out we are journalists, smiling and asking our names.

Holding his emaciated arm, Halyna says it's clear from his poor physical condition that he spends most of his time in bed.

"I just am concerned about the potential that he hasn't lived up to, because he has been in here for his whole life," Halyna says.

Before the war, Ukraine was already one of the poorest countries in Europe.

Poverty and a lack of support for struggling families contribute to a mindset that these facilities are necessary.

That's what the director of Oleh's institution, Mykola Sukholytkyi, believes.

"It is better for children with disabilities to live here, rather than with their families," he says.

"Instead of being in dysfunctional families where they can be uncared for, without food, here they can benefit from all the essentials."

Eric says the billions of dollars of international aid being pumped into Ukraine during the war should also be used to shut down orphanages, support families to care for their children and build a community that accepts disability.

"We know orphanages do not need to exist," he says.

He fears some of the money could be spent on maintaining institutions - and that after the war ends, "the international attention to Ukraine will end and the orphanages will continue as they are".

After a long hot day in the yard of his orphanage, it's time for Vasyl to say goodbye to his parents.

He is still tied up. He is still screaming.

Maryna says as she leaves that she is "very grateful to the institution".

But she adds: "Our children with disabilities should not be hidden away from society, behind these high walls."

- Published4 May 2022

- Published9 May 2022

- Published23 February 2017

- Published6 April 2016