Can universities tackle social divide?

- Published

Oxford University has indicated it is likely to charge the top £9,000 fee

It's a conundrum almost as old as England's greatest universities themselves - how to attract more students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

And it is one that the majority of the most selective institutions are still failing to crack - despite their best efforts.

A report by England's Director of Fair Access Sir Martin Harris last spring revealed there had been "no overall change" over the previous 20 years in the rates of disadvantaged youngsters studying at the most competitive universities.

The report also found the gap in participation rates of disadvantaged students between the most selective universities and the rest had widened.

The government is setting out its requirements of universities in England in the new landscape of higher tuition fees, with special conditions for those wishing to charge more than £6,000 a year.

And it is not difficult to see how fears over debts resulting from annual tuition fees as high as £9,000 could deter even more students from poorer backgrounds.

The Russell Group, which represents the most selective institutions, is the group of universities thought most likely to opt for the higher fee level.

These universities spend millions of pounds every year on schemes, like summer schools, outreach programmes and bursaries to attract more students from non-traditional backgrounds.

But the group has long argued that universities cannot be social engineers.

Its director general Dr Wendy Piatt said it was beyond her group's "power to solve this problem" which she sees as under-achievement in schools.

"It would be quite unfair to punish universities for a problem which lies elsewhere in the educational system," she says.

Sir Martin's report says good A-level results are the "single most important factor" in obtaining a place at a selective institution or on a very competitive course.

And research shows that the link between socio-economic background and educational attainment is visible before a child reaches the age of two.

This attainment gap continues to widen as children progress through primary and secondary school, further studies show.

'Through the cracks'

Dr Graeme Atherton, director of a London arm of the national widening participation scheme Aimhigher, said it was wrong to focus exclusively on the efforts of universities.

"If you think about the sort of kids the Russell Group want to attract - if you are talking about a bright pupil on a free school meal - there are not going to be that many of them."

"If you look at the Premier League football clubs - they identify talents very early on and then nurture them."

But he adds: "Universities would agree that it is very difficult to identify these young people.

"They may be in schools that have great challenges - schools that are in special measures.

"And if you are going to get them, you are going to need someone who is working with them."

'Intimidated'

Research for Aimhigher found schools needed a dedicated member of staff, perhaps a teacher or a careers adviser, to ensure that bright pupils do not fall through the cracks.

Head teachers simply do not have enough time to do this themselves, he says.

Dr Atherton's organisation is a national partnership of 2,500 schools, 300 colleges and 100 universities attempting to raise the aspirations of low income pupils in the early years of secondary and final years or primary school.

However, Aimhigher will no longer receive government funding from the end of July this year.

It will be left up to universities themselves to make their own arrangements for widening access.

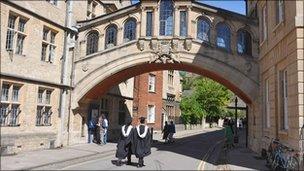

Some communities feel universities would not welcome them

Tricia Jenkins, director of educational opportunities at the University of Liverpool, says gaps in expectation have to be addressed at an early age.

She works with primary school children in Greater Merseyside to help them to think positively about university. The university has some 15,000 children in for visits every year.

Using a cuddly toy with a mortar board on its head, called Professor Fluffy, she invites pupils to talk about their feelings towards education and university.

And she gently gets them to see it as something that could be a possiblity for them.

Her programme has led to a 300% increase in applications from students from poorer backgrounds through the universities Scholars scheme.

"The reason why one child goes to university and another does not has nothing to do with ability it is all to do with expectations," she says.

This view is echoed by Marius Frank, the former head of Bedminster Down comprehensive school in a deprived area of Bristol, now the head of educational charity Asdan.

He recalls his own attempts to encourage his own secondary pupils to consider attending the university just a few miles across the city.

"We took the students to Bristol University and we put on a coach for their parents as well.

"It was the first time we did it and I'll never forget it.

"The parents were very few in number and very intimidated - they just did not know what they were doing there.

"It was then I realised how big the gap in experience and expectation was that has to be bridged to make it work."

- Published10 February 2011