State schools 'failing girls who want to study physics'

- Published

- comments

Teachers should challenge the misconception that physics is not for girls

Nearly half of all state schools in England do not send any girls on to study A-level physics, research by the Institute of Physics (IOP) has found.

The IOP study, external indicates that the situation is likely to be similar in schools across the UK.

The research also shows that girls are much more likely to study A-level physics if they are in a girls' school.

The Department for Education said it was working to attract top physics graduates into teaching with bursaries.

An analysis of data from the national pupil database showed that 49% of state co-educational schools in England did not send any girls to study physics at A-level in 2011.

Girls were two-and-a-half times more likely to go on to study A-level physics if they came from a girls' school. The same is not true of other science subjects, suggesting that physics is uniquely stereotyped in many mixed schools as a boys' subject.

The study was of English schools because comparable data is not available from schools in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. But the disparity and problems were likely to be largely similar, the IOP said.

It said that schools should be set targets by the government to increase the proportion of girls studying physics from the current national average of just one in five.

It has also asked head teachers to challenge the misconception among teaching staff that physics is not for girls.

Girls at Lampton School in London talk about why they love physics

There has been a slight increase in the number of girls studying physics in recent years but this has been dwarfed by a more rapid increase in boys studying the subject.

In 2011 physics was the fourth most popular subject for A-levels for boys in England. For girls it was the 19th most popular. IOP president Prof Sir Peter Knight says many girls are not receiving the education they are "entitled to".

"The English teacher who looks askance at the girl who takes an interest in physics or the lack of female physicists on television, for example, can play a part in forming girls' perception of the subject. We need to ensure that we are not unfairly prejudicing girls against a subject that they could hugely benefit from engaging with," he said.

Some felt the European Union's "Science: It's a Girl Thing" missed the mark and caused great offence

The salaries of physics graduates are well above the national average. Over a working lifetime, the average physics graduate earns about £100,000 more than graduates of non-science subjects.

Prof Knight said: "Physics is a subject that opens doors to exciting higher education and career opportunities. This research shows that half of England's state schools are keeping these doors firmly shut to girls."

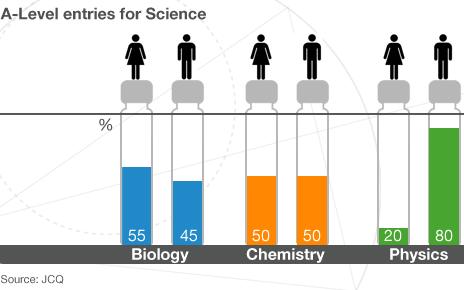

The disparity is much greater for physics than any other science subject. There are slightly more A-level entries for biology from girls in 2012, for chemistry the numbers are about the same and 40% of pupils studying A-level maths are girls. Of those studying A-level physics, only 20% are girls.

Dr Heather Williams is a medical physicist working for the NHS and head of ScienceGrrl, an organisation trying to inspire more girls to study science. She believes that while many attitudes toward women have changed across many areas of society, science, and physics in particular, remain stuck in the past.

"Physical sciences are seen as a male dominated area," she said.

"That's partly because there is a lack of visibility of female physicists to act as role models and so girls don't see themselves following a number of career paths."

Prof Athene Donald, a physicist and gender equality champion at the University of Cambridge also feels a lack of role models is partly to blame.

"These figures are eye-wateringly bad and it is extremely depressing to see how many schools fail to excite girls' appetite for physics.

"From the statistics alone it is impossible to tell whether this is due to factors within the school, peer pressures and cultural cues, lack of role models or a genuine lack of interest in the subject.

"That girls from single sex girls' schools don't seem to lack interest in physics, however, suggests it is not the last of these. It is to be hoped that these figures will serve as a wake-up call to schools to investigate where the problems do lie."

Earlier this year the European Commission launched a video, external taster of an initiative to engage more girls in science called Science: It's a Girl Thing. The video aimed to reach out to a young female audience normally uninterested in science by having a pop feel.

There is some market research information that indicates that girls did find the imagery positive, engaging and fun. But many, including Dr Williams found the video offensive.

The anger generated by the video was the impetus for the formation ScienceGrrl (hence the Grr). Dr Williams believes efforts to engage girls by telling them that science is relevant to cosmetics and fashion are misguided.

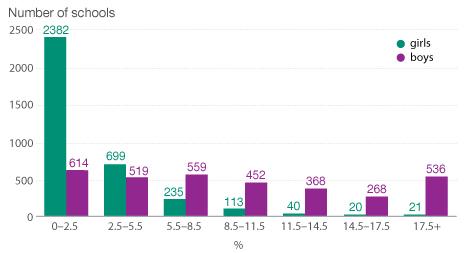

Girls and boys that went on to take physics A-level (%)

"The thing that I would object to is that that is not what science looks like. It is actually something that I find useful and fascinating and fun."

A Department for Education spokesman said: "We are working with the Institute of Physics to attract the brightest physics graduates into teaching with the highest ever bursaries.

"We are also giving the IOP £6.85m over the period 2011-14 to provide an inspiring, engaging and innovative programme of physics lessons and continuing professional development for teachers.

"We want to see new recruits developing pupils' interest in the subject and pushing schools with low take-up and attainment in physics to encourage more girls to study physics at A-level."

Follow Pallab on Twitter, external

- Published16 August 2012

- Published3 August 2012

- Published29 July 2011