England's young adults trail world in literacy and maths

- Published

- comments

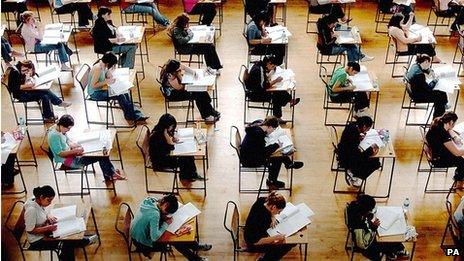

Despite decades of rising exam results, young adults have shown little progress

Young adults in England have scored among the lowest results in the industrialised world in international literacy and numeracy tests.

A major study by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) shows how England's 16 to 24-year-olds are falling behind their Asian and European counterparts.

England is 22nd for literacy and 21st for numeracy out of 24 countries.

The OECD's Andreas Schleicher warned of a shrinking pool of skilled workers.

Unlike other developed countries, the study also showed that young people in England are no better at these tests than older people, in the 55 to 65 age range.

When this is weighted with other factors, such as the socio-economic background of people taking the test, it shows that England is the only country in the survey where results are going backwards - with the older cohort better than the younger.

'Shocking'

The study shows that there are 8.5 million adults in England and Northern Ireland with the numeracy levels of a 10-year-old.

"This shocking report shows England has some of the least literate and numerate young adults in the developed world," said Skills Minister Matthew Hancock.

"These are Labour's children, educated under a Labour government and force-fed a diet of dumbing down and low expectations."

Ministers in England have announced a new maths qualification for 16 to 18 year olds as part of a drive to improve numeracy and its requirement that maths should be studied until the age 18 for those who do not have a good GCSE in the subject.

The newly-appointed shadow education secretary Tristram Hunt defended Labour's record.

"Labour drove up standards in maths and English across our schools, evident in the huge improvements we saw in GCSE results between 1997 and 2010."

He said a future Labour government would "ensure all young people study maths and English to 18" and would not allow "unqualified teachers to teach in our classrooms on a permanent basis".

Young adults in Northern Ireland performed better in the OECD tests than in England, but they were also in the bottom half of these rankings.

The highest-performing countries among this younger age group were Japan, Finland and the Netherlands. The country with the lowest numeracy skills was the United States, plummeting from once being one of the strongest education systems.

This landmark study from the OECD set out to measure the level of skills within the adult population - testing actual ability in literacy, numeracy and digital skills, rather than looking at qualifications.

It involved 166,000 adults taking tests in 24 education systems, representing populations of 724 million people. From the UK, adults in England and Northern Ireland participated.

The study looked at the level of skills across the adult population, between the ages of 16 and 65. England and Northern Ireland are below average for both literacy and numeracy, in league tables headed by Japan and Finland.

But for most industrialised countries the younger population are much better at such tests than the older generations.

Dr Jasper Kim: "If you're a wealthy family... you can pay for performance, but if you're in the bottom tier you can be left behind"

Mr Schleicher pointed to the examples of Finland and South Korea where there had been huge progress in recent decades.

A statement from the Finnish embassy highlighted that this was about a long term commitment to improving schools.

"This demonstrates that there is a longer trend in the Finnish education success, it is not just something that has happened in recent years."

However, for England, when the results are separated from Northern Ireland, there was a different and unusual pattern, with almost no advance in test results between the 55 to 65-year-olds and those aged 16 to 24.

This younger group will have many more qualifications, but the test results show that these younger people have no greater ability than those approaching retirement who left schools with much lower qualifications in the 1960s and 1970s.

The grandchildren are not any better at these core skills than their grandparents.

Global race

Mr Schleicher says it might suggest evidence of grade inflation and it shows that better qualifications do not necessarily mean better skills.

"When you look at this snapshot you do have to conclude that these young people are not any better skilled when it comes to those foundation skills than people in the older generation," he said.

He warned of the serious economic implications of a failure to provide a skilled workforce.

Andreas Schleicher has warned that young adults in England are falling behind other countries

The influential OECD expert showed how there was an increasing demand in the jobs market for those with higher skills - and a static or falling jobs market for those with lower skills.

England and Northern Ireland have particularly high levels of adults with the lowest skill level in literacy and numeracy.

The economic and social rewards for having high skills are particularly strong in England and Northern Ireland, says the research, with significant advantages in health, job opportunities and income.

The global economic race is strongly linked to educational performance and the OECD report shows how the UK's share of the highest skilled workers is falling.

An even sharper decline is faced by the United States, an education superpower of a previous generation. Last year the OECD warned that the US was almost the only developed country facing educational "downward mobility", where the younger population is less well educated than the older generation.

This latest study shows that the US once had 42% of the world's highest-skilled adults but this had now fallen to 28%.

Mr Schleicher set out the scale of the difference in ability, saying that many secondary school pupils in Japan were ahead of graduates in England.

Neil Carberry, the CBI's director for employment and skills, said the UK's economic future depended on improving the skills of the workforce.

"This survey simply emphasises that the UK cannot afford to stand still on skills."

Ian Brinkley, director at the Work Foundation think tank, said the study showed the UK faced a "relative decline in the economy's skills base".

"We face a major generational challenge."

- Published8 October 2013

- Published3 December 2012

- Published11 July 2012

- Published2 March 2011

- Published27 November 2012