Social mobility: 'Britain remains deeply divided'

- Published

Mr Milburn said the UK had more children living in poverty than "many other nations"

Alan Milburn says he was asked by the coalition to "hold its feet to the fire" in examining its progress on social mobility and child poverty.

But just how much will his words hurt?

In this, the first of what is planned to be an annual "State of the Nation report", the commission led by the former Labour health secretary concludes that "Britain remains a deeply divided country", one where "being born poor often leads to a lifetime of poverty".

The commission says austerity has made it even harder to break ingrained cycles of poverty, that "disadvantage and advantage cascade down the generations".

It warns there is a danger that social mobility will go in to reverse after rising in the middle of the last century and "flatlining" towards the end of it.

The post-war years saw a big expansion of the middle classes, as the professional jobs market grew and more people bought their own homes, but there has been little change in the last quarter of the century.

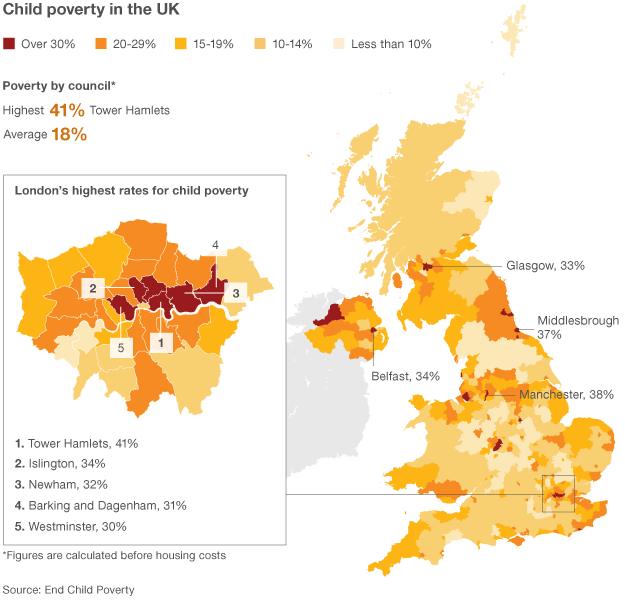

Mr Milburn said over decades, the UK had become a wealthier society, but had "struggled to become a fairer one" and had more children living in poverty and lower levels of social mobility than "many other developed nations".

A total of 2.3 million children (one in six) live in poverty, he said, and this made it essential that the pattern where "birth not worth" determined a person's chances in life was changed.

Higher social mobility had become "the new holy grail of public policy". It is certainly something all parties now say they want to see.

'Generational unfairness'

The report from the Social Mobility and Child Poverty Commission, external has stinging words on some areas of government policy but they are sweetened with praise for others, including the fact that the coalition continues to "stick to its commitments" on ending child poverty and improving social mobility in "challenging times".

Mr Milburn told journalists at a news conference the government "deserved credit" for that.

But the target of ending child poverty by 2020 - begun under Labour and continued by the coalition government - would "in all likelihood" be missed, he said.

His most stinging criticism seemed to be about the way the young were likely to pay the highest price for a lack of social mobility and poverty during the global financial crisis.

He called for older generations to be asked to dig deeper.

The number of young people who have been unemployed for two years or more is at a "20-year high", he said.

And there was an "inter-generational unfairness" in terms of who was being asked to pick up the bill in the recession.

He did not call for pension cuts, but Mr Milburn said politicians should be prepared to "break political taboos" to talk about whether wealthier pensioners should lose benefits currently available to all - particularly the winter fuel allowance and the free TV licence.

Pensioners were usually more worried about their grandchildren than themselves, he said.

The commission is also looking to employers to do more - to offer better training, pay higher wages and open up professions to a wider pool of people. Two-thirds of children living in poverty, the report says, are living in homes with a working parent.

Schools and universities were also urged to do more.

He said schools in some areas were letting down pupils from poorer homes and those from middle-income homes too.

Schools should give more help to low-achievers from middle-income homes as well as the poorest, while the government should improve careers advice, give extra incentives for teachers to teach in the worst schools and pay colleges "by results they achieve for their students in the labour market - not the numbers they recruit".

'Missing state school pupils'

As for universities - which were the focus of an earlier report by the commission - he says the sector as a whole has drawn in more students from poorer homes but top institutions remain out of reach for too many.

Each year, he said, there were 3,700 "missing" state school pupils who had achieved the grades needed to get in to universities in the Russell Group (which represents some of the UK's leading universities) but did not go to them.

The commission called for the government to put social mobility at the heart of its policies and practices, so that it was a "golden thread" running through all it did. It concentrated on the overall UK picture, but pointed out that in Scotland and Wales, the issue "currently has a low profile".

In an age of austerity, the report's authors suggest creating a fairer society will be a job for all - and far from pain-free.

- Published17 October 2013

- Published17 October 2013

- Published16 October 2013

- Published18 September 2013

- Published24 June 2013

- Published17 June 2013

- Published30 May 2012

- Published5 June 2013

- Published11 July 2012