Afghan school growth 'will survive political upheavals'

- Published

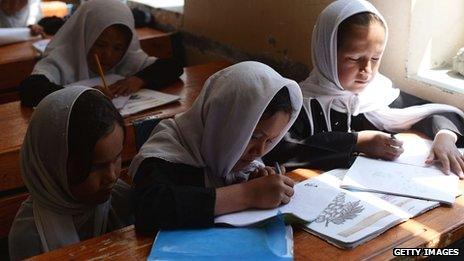

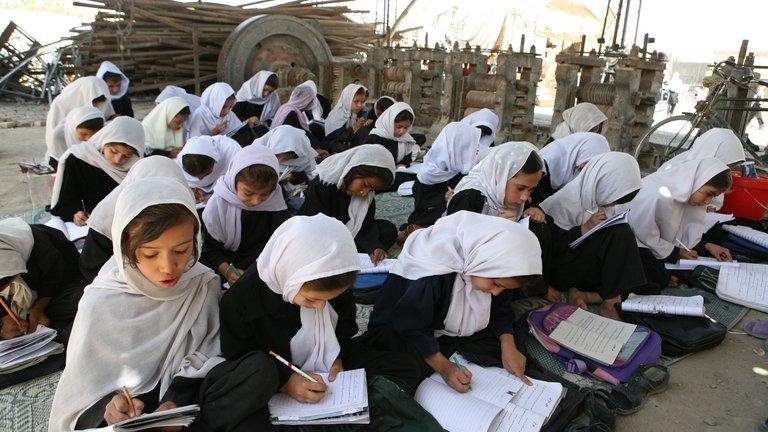

Increasing numbers of girls are attending school in Afghanistan

Afghanistan's progress in reopening schools is irreversible and will survive any political upheavals, the country's Education Minister, Farooq Wardak, has said.

Mr Wardak said local communities were driving the demand for education and would protect schools after the withdrawal of overseas forces.

He said the Taliban were guaranteeing the safety of schools in some regions.

The minister said by 2020 every child would have a primary place.

Mr Wardak promised that an equal number of boys and girls would be being enrolled, by the same date.

Re-opening schools

Speaking in London, Mr Wardak said there had been a major grassroots change in support of the campaign to widen access to schools across Afghanistan.

He said there had been a "revolution" in the way that groups of local leaders, parents and religious scholars were now actively defending the right to education.

"People who themselves are illiterate want an education for their children."

This popular pressure for schools had a momentum all political sides would have to accept, he said.

Farooq Wardak says Afghanistan must invest in education for a stable future

There are 700 schools that had been shut down by attacks but have now reopened.

The Afghan education ministry says that pupil numbers have risen from 900,000 in 2001, with few girls in attendance, to 10.5 million pupils, including 42% girls.

A decade ago, only 400 teachers were being trained - but now, Mr Wardak said, there were 77,000, most of them women.

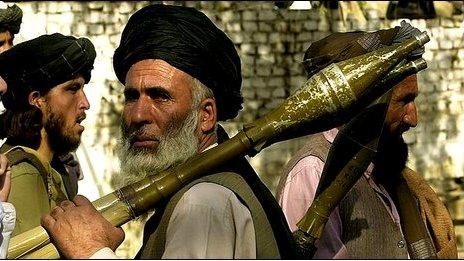

A report last summer from the United Nations highlighted the scale of the challenge, saying there were 167 separate documented attacks on education, including intimidation, abduction, killing of staff and the destruction of buildings.

These were attributed to a range of armed groups, not only those linked to the Taliban.

And Mr Wardak said opposition from the Taliban was changing in some places.

He told of a local Taliban leader summoning head teachers to say that he would hang anyone who attempted, using the name of the Taliban, to disrupt their schools.

Conflict zones

The minister said investing in education was vital to Afghanistan's economic and political stability.

Tackling illiteracy was the starting point for much wider changes, such as stopping people being used as suicide bombers, he said.

Mr Wardak said his goal was to see Afghanistan as a "mainstream member of the world community", providing support for other countries rather than being a recipient.

A particular expertise, he said, was that Afghanistan had had to learn how to deliver education in a conflict zone.

"We've had to work with conflict for 35 years," he said. Mr Wardak himself became a refugee in Pakistan after the Soviet invasion.

There have also been drives against corruption. He said a policy to check teacher proficiency was also a way of detecting so-called "ghost teachers", where salaries were being claimed for non-existent staff.

This saw about 2,000 names disappearing from the payroll.

"We can't tolerate the stealing of money from innocent children," he said.

Mr Wardak's campaign for education has been supported by the Global Partnership for Education.

This international body, funded by governments including the UK, has allocated $3.25bn (£1.97bn) in the past decade to help improve education in 59 developing countries.

Mr Wardak made an impassioned case for the future of Afghanistan's education system.

He said the country's long tradition of scholarship had become the "victim of international wars" and needed to be restored for a prosperous and peaceful future.

"We are the product of our education, but we forget to pay it back," he said.

- Published27 January 2014

- Published23 May 2012

- Published26 January 2014