GCSE grades rise, but sharp fall in English

- Published

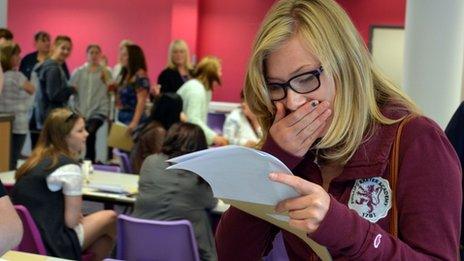

The BBC's Ben Bland joins "shocked" students opening their results in Norwich

There has been a sharp fall in English GCSE grades, but on average across all GCSE subjects this year's results show a rise in A* to C grades.

Hundreds of thousands of pupils in England, Wales and Northern Ireland have been receiving their GCSE results.

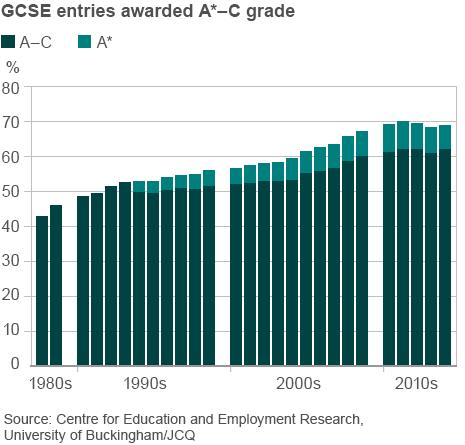

Exam officials revealed that 68.8% of entries scored A*-C, up 0.7 percentage points on last summer.

There have been warnings of "volatility" in results following an overhaul of the exam system.

Brian Lightman, head of the Association of School and College Leaders, said a "significant minority" of schools had not received their predicted results with schools with many disadvantaged students having been "hit the hardest".

"The volume of change has made year on year comparisons in GCSE results increasingly meaningless. It is almost apples and oranges," said Mr Lightman.

Older entry

Andrew Hall, head of the AQA exam board, said the most significant impact on this year's results has been the big fall in younger pupils taking exams a year early. Changes in the league tables discouraged schools from such multiple entries.

GCSE results

At-a-glance

68.8%

scored A*-C grade

98.5%

pass rate, down 0.3 percentage points

-

6.7% awarded A* grade

-

62.4% Maths entries graded C or above, a rise of 4.8 percentage points

-

61.7% English entries graded C or above, a fall of 1.9 percentage points

With fewer young exam candidates, there was a sharp improvement in maths results where the percentage achieving A* to C grades rose by 4.8 percentage points to 62.4%.

The proportion of pupils getting the top A* grade across all subjects fell slightly to 6.7%, down from 6.8% last year.

There were significant differences between the A* to C grade results in England, Wales and Northern Ireland - where increasingly dissimilar versions of GCSE are being taught. Results rose in each of the three education systems.

Holly Sayer, who is dyslexic, won an A* in English literature at the ARK Charter Academy in Portsmouth

Northern Ireland: 78% (76.5% in 2013)

England: 68.6% (67.9%)

Wales: 66.6% (65.7%)

The reforms to GCSE, such as the switch to linear, non-modular courses and less coursework, have applied only to England.

The results in English seem to have been most affected, with the number of A*-C grades down 1.9 percentage points to 61.7%. This was also influenced by the removal of the "speaking and listening" element of the subject.

The CBI's deputy director general, Katja Hall, said exam reforms have helped to increase "rigour".

But from an employer's perspective, she said more was needed to ensure a GCSE grade was an accurate measure of "skills they can bring to the workplace". The removal of speaking and listening from the English GCSE was "particularly concerning", said Ms Hall.

Kai Konishi-Dukes, from King's College, Wimbledon, got top grades in all 15 of his GCSEs

She also warned that "we cannot continue to turn a blind eye" to the question of whether there should be such an exam for 16 year olds.

There is still a significant gender gap in this year's results, with 73.1% of girls' exam entries achieving A* to C compared with 64.3% for boys.

Exam officials also highlighted a fall in the numbers of entries for biology, chemistry and physics, the first such decline for a decade.

'Volatility'

Michael Turner, director general of the Joint Council for Qualifications, said although the overall results were "relatively stable", individual schools and colleges could see "volatility in their results".

Glenys Stacey, chief executive of the Ofqual exam regulator, has also warned that changes in the exam system could hit individual schools in different ways.

School Reform Minister Nick Gibb welcomed the 40% drop in early exam entries and said the changes were necessary to "correct" a system that had "worked against the best efforts of teachers and the best interests of pupils".

"Pupils and parents can feel increasingly confident that the exam system is now working in their favour - that the GCSEs and subjects they are taking are those most valued by colleges, employers and universities."

Labour's shadow education secretary Tristram Hunt highlighted concerns about schools being able to hire staff without formal teaching qualifications.

"It is now the case that some of the pupils who have received their grades today may have higher qualifications than the teachers who will be teaching them at the start of the next school term," claimed Mr Hunt.

Alan Smithers, director of the Centre for Education and Employment at Buckingham University, warned of "shocks in store" for some schools, depending on "how much they relied on gaming the old system".

'Piecemeal change'

"All of this piecemeal change to GCSE means that is incredibly difficult for schools to forecast what grades students might expect to achieve, or indeed to compare the school's results with previous years," said head teachers' leader Brian Lightman.

"Consequently the statistical trends are becoming less and less meaningful.

Schools Minister Nick Gibb MP defends the government's policy

"Young people are not statistics. They are individuals whose life chances depend on these results. They have worked extremely hard for these exams and been conscientiously supported by their teachers. I hope that their results do them justice."

Chris Keates, leader of the NASUWT teachers' union, said this year's GCSE exam entrants had to "cope with a raft of rushed through and ill-conceived changes to the qualifications system and so today's results are especially commendable".

The National Union of Teachers' leader Christine Blower said that the headline figures "mask underlying issues which will only become clear over time".

"We must ensure that changes being made to our qualifications system do not unfairly disadvantage specific groups of students, including those with special educational needs or those from backgrounds of economic disadvantage."

- Published21 August 2014

- Published21 August 2014

- Published21 August 2014

- Published21 August 2014

- Published21 August 2014

- Published21 August 2014

- Published1 August 2014