Swings and roundabouts for skills funding

- Published

Tony Blair is said to have once joked that you could hide a declaration of war in a speech about skills and no-one would ever notice it. He might still be right.

Last week, while Labour was setting out its plans to tinker with university funding, the government released largely unnoticed news of a significant budget cut. The skills budget is being trimmed by 5% from this year into next year - but that number disguises bigger swings.

Since 2010, a lot of college costs which were previously covered by government grants have been switched to be covered by fees. The state is paying less and students more. To ease that transition, further education students have been allowed access to loans on the same terms as university students.

There is an exception: apprenticeships - state-subsidised in-work training positions - were (eventually) exempted from that trend and given more funding.

As other routes by which adults could get subsidised on-the-job training were cut back, the number of apprenticeships rocketed up from 279,900 in 2009-10 to 440,000 in 2013-14, although growth has now stopped.

Financial trouble

The new cuts run along those lines. The budget for direct subsidy of non-apprenticeship adult skills is falling by 24% this year to about £1.2bn. The amount set aside for further education (FE) loans rose from £398m to £498m, while apprenticeship spending for adults was frozen at £770m.

The colleges are terrified by this latest switch and have come out swinging. Before this announcement, even if you include both apprenticeship spending and income from FE student loans, the adult skills budget had been cut by one fifth since 2009-10. Their concerns are partly because of the ever-changing landscape, partly because they think the loan facility won't be used in full. Then of course there are the cuts.

That squeeze has been little noted outside FE, education's self-described "Cinderella sector". The whole adult FE system runs for £4bn. By contrast, Labour's plan to tinker with university tuition fees cost about £3bn, and universities have an annual income of about £30bn.

Indeed, you would be forgiven for not knowing how enormous the system really is. In 2013-14, there were 1.3m full-time and 556,000 part-time British students at UK universities. In the same year, 2.9m adults were at further education colleges.

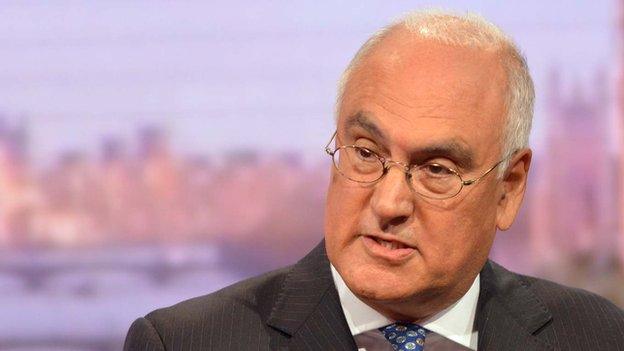

Sir Michael Wilshaw, head of Ofsted, has said he wants to "shine a light" on the FE sector's performance

But, right now, the sector is struggling: 20 of the 230 public FE colleges were in serious financial trouble in 2014-15. According to the Association of Colleges, another 30 could be financially weak. There is also concern about the quality of a lot of colleges and tuition.

Sir Michael Wilshaw, the chief inspector, back in 2012, said he wanted to "shine a light" on the sector's performance. It has not been fixed: the problems have roots in how FE fits into the education system and unpredictable budgets that make planning impossible.

Britain has a longstanding difficulty in this area - we've been fretting about it since the mid-19th century. But further education is now much more important than it was. If we want people to work longer, they are more likely to need to retrained in applied, technical skills.

More importantly, the majority of young people still do not want to go to university. For them, any state-supported education they get is likely to come through FE, whether it is on-the-job training or it could mean a class.

So far, the major parties' announcements on technical and vocational education have focussed on the funding of apprenticeship places and curricula for under-18s. (I wrote about the various pledges on apprenticeships over here.)

But the parties must also talk about how they can help the colleges get better at what they need to do. That would almost certainly mean giving the colleges more certainty about their futures, even if it doesn't mean more money.

- Published16 February 2015

- Published16 February 2015

- Published17 October 2014