Birmingham University seeks free school innovation

- Published

University of Birmingham School has a striking design

Inside, the University of Birmingham School is a startling laboratory white.

An appropriate background, you might think, for an experiment.

It is the first secondary school to be opened by a university in the controversial free school, external programme.

A similar primary school, external has just opened under the control of the University of Cambridge.

What sets these schools apart is their scale and ambition, and perhaps their potential for innovation.

Showing me round the school in Birmingham, head teacher Michael Roden says they are working with the Jubilee Centre, external at the university to embed the nurturing of character into every lesson.

This turns out to be a tricky concept to pin down, as I ask him how a parent or child would notice the difference.

"We're trying to get the children to think, to use what the Greeks called phronesis, or good sense - making, as my mum would say, common-sense decisions."

There is also an open ethos, with every classroom wired so lessons can be streamed for teacher training and research.

Diversity

For the staff it seems there is no place to hide. The glass walls of their common room overlook the main hall and dining area.

It allows for passive monitoring, Mr Roden tells me.

That, of course, can work both ways.

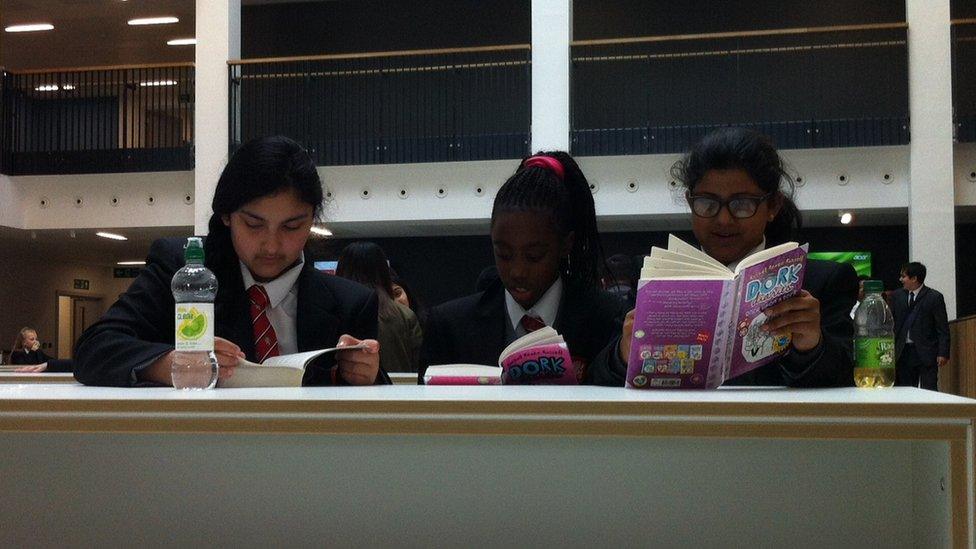

In the classrooms it becomes apparent that the diversity of pupils is one of the most distinctive features.

Pupils are being taught to think for themselves

They are drawn from more than 60 primary schools in Birmingham.

That includes some from the leafy suburbs around the building, but also three inner city areas which are considerably more deprived.

It's a bold gesture in a city where there has been a concern about communities looking inwards rather than towards each other.

As well as the sciences, there is a commitment to music and art.

The hours are slightly longer than in many schools, from 08:30 to 16:30, to allow extra activities to be built into the school day.

Free schools in England

340 free schools are open or preparing to open

136 had had inspection reports published by August

34 were outstanding

72 were good

24 require improvement

Six were judged inadequate, with a seventh added in September

For Mr Roden, the chance to start afresh in a new building with staff he has chosen is obviously appealing.

For the University of Birmingham the risks are substantial and the potential gains less immediately obvious.

It has invested more than £2m in cash on a site worth several million more, and it has also invested its reputation.

Vice Chancellor Prof Sir David Eastwood says the plan is for the school to work with the university's School of Education to innovate in the way children are taught.

They would not have considered taking the risk outside the free school programme, he says.

"It was only the free school model which would give us the kind of flexibilities we needed as a university - to shape the curriculum, to work in partnership with the school, to have the focus on teacher education, to have a focus on building character in children in the school."

'Free thinking'

The University of Cambridge primary free school also says it intends to innovate and be "bold, free-thinking and rigorous".

Backed by elite universities, these schools may, in time, produce interesting ideas.

Like all free schools, they will also have to navigate the expectations of parents and Ofsted - influences which may make it harder to do something radically different.

The Department for Education in England published its own analysis, external last year on innovation in free schools.

School principal Michael Roden lays the final brick in the front wall

It said that 62% were teaching an alternative to the national curriculum in some or all subjects and more than half had a longer school day.

But Prof Francis Green at the Institute of Education is sceptical about how much real experimentation there has been.

He is researching innovation in free schools and says the initial evidence is that changes have been modest.

"They lengthened the working day a bit, they had a slight variation from the national pay norm, they may have instituted some after-school childcare. [These are] things which actually take place quite often in state schools."

The free school programme has been a high-stakes political move, bypassing local councils and their role in planning for school places.

It was a deliberate disruption of the school system in England, with the intention of allowing new ideas to flourish.

Prof Green says as free schools mature, demonstrating that they are truly innovative will become more important.

"Few countries have gone through such a revolution in school systems over the last five to 10 years as we have - and it's very important that we see some dividends from this."

Experimental

Such dividends must more than compensate for the failures. Four free schools have closed and seven have been judged to be failing since 2013.

So far, Ofsted has resisted making any firm judgement on free schools overall, but as more reach the point of being inspected, that may change.

The University of Birmingham is putting its own reputation on the line with the new school

By 2020 another 500 free schools are promised. The reality is that every new school opening in England will be called a free school.

Many are likely to be opened by existing academy chains, some in response to requests by local authorities desperate for more school places.

The most experimental part of the free schools could well turn out to be the first five years.

And the most ambitious versions could be those that involve the resources and research capacity of universities.

- Published26 May 2015

- Published25 September 2014

- Published2 September 2015

- Published9 March 2015