Migrants 'do not lower school results'

- Published

Refugees arriving in Germany: The OECD says migrants are assets to education systems

Higher levels of immigration do not damage educational achievement in the host country, a global study from the OECD economic think tank suggests.

It found no link between the numbers of migrant children and the performance of school systems.

But it indicated wide gaps in a sense of "belonging" - with the lowest levels among migrant students in France.

The OECD's Andreas Schleicher said many migrant families were "hugely motivated" to succeed in education.

The study also examined how much young migrants identified with their school or felt excluded.

It found that migrant pupils in the UK and the US were particularly likely to be positive about schools in their adopted country - while in France and Belgium, they were among the least likely to feel a sense of belonging.

The international think tank says the research has been carried out against the backdrop of "unprecedented" numbers of refugee families arriving in Europe.

This has raised concerns about the pressure put on services such as education - and raised questions about standards being jeopardised by absorbing higher numbers of migrants.

Researchers say teachers need to understand issues such as trauma

The OECD, which runs the global Pisa tests, examined migration between 2000 and 2012 and concluded that there were no links to lower performance in school systems.

Migrants, on average about 11% of pupils in OECD countries, were more likely to be an "asset than a liability" in terms of school standards, it said.

Researchers found that the achievement of migrants varied depending on where they had settled.

As an example, Iraqi children in schools in Finland were higher achievers than Iraqi children in Denmark.

The OECD highlighted Germany as having improved in ensuring that migrant children were not falling behind. There were other countries, such as Canada and Australia, which continued with an established history of successfully settling new arrivals.

In Singapore and Hong Kong, migrant pupils were doing well within an overall system that was very high achieving.

Families crossing the Greek-Macedonian border on Monday

The OECD said migrant parents could be more ambitious than the native population, with examples including Belgium, Germany and Hungary.

But there could be wide differences in how much pupils identified with their schools.

In most countries, migrants felt a weaker sense of "belonging" at school than non-migrants. The two main exceptions were the UK and the US, where the sense of belonging was higher among migrants than the general population.

France had the lowest sense of belonging among first-generation migrants - and for second-generation migrants the figure was even lower. In Denmark, there was also a pattern of second-generation migrants being more "alienated" from school.

The study suggested different levels of integration. Students from Turkey felt a strong sense of belonging in Finland, but much weaker in Belgium and Denmark.

Mr Schleicher, the OECD's director of education, said a "clear policy lesson" was the problem of too many migrant pupils being concentrated in a small number of low-achieving schools.

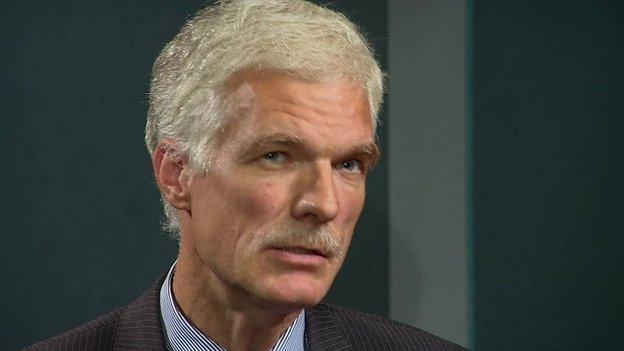

Andreas Schleicher's study highlights the ambitions of migrant families for their children

This could lead to a "concentration of disadvantage", with poor migrants crowded into poorer parts of a city and being sent to schools with weaker results.

This downward spiral was worst in Greece, Belgium, Netherlands, Slovenia and Italy.

In the UK, schools with a high proportion of migrant families did not perform any differently from the average.

The study also examined the factors that could make a positive difference.

Overcoming language barriers was seen to be critical - and the report said pupils did much better if they were immersed within mainstream lessons, rather than being taught separately with other language learners.

The provision of early years education was seen as an important intervention.

The OECD also called for teachers to be aware of problems such as refugee children who had faced trauma.

This study examined migration before the arrival of hundreds of thousands of families from the conflict in Syria.

But Mr Schleicher said the reality across Europe was that most teachers now had pupils from a diverse range of backgrounds.

He said the study showed there was nothing inevitable about the success or failure of migrant children.

"It's a question of political will," he added.

- Published17 November 2015

- Published7 October 2015