Are cities the new countries?

- Published

Are big cities becoming more like separate countries?

Do big cities have more in common with each other than with the rest of their own countries?

Are there meaningful comparisons between cities such as New York, London and Shanghai, rather than between nation states?

That is the suggestion of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Such mega-conurbations have bigger populations and economies than many individual countries - and the think tank argues that they face many similar challenges, whether it is in transport, housing, security, jobs, migration or education.

In a report on global trends shaping education, external, the OECD says cities could learn from each other's experiences, in a way that would be impossible at the level of national politics.

"Sharing policy lessons across countries is hard, because policy is so much framed in terms of ideology and political parties," says Andreas Schleicher, the OECD's education director.

"When we talk about countries, it's often about what separates us, language and culture. But when you talk about cities, we face very similar challenges."

They are the upsides and downsides of immense concentrations of people living in a small space, often two sides of the same coin.

Japan is one of the most urbanised countries in the world

There are more jobs, but also more unemployed. There are extremes of wealth and poverty. There are highly developed transport systems and then overcrowding as they struggle to cope with the demand.

The bright lights, the economy and innovation attract people which leads to extra pressures on housing and services and arguments over the levels of migration.

Modern mega-cities are highly connected places, but with corresponding levels of people who feel dangerously disconnected.

These are issues that the OECD says could be more usefully examined at a city level.

"If you think of security, terrorism and radicalisation, it's not going to be a challenge for the villages of England or France - it's going to be large metropolitan areas that are going to have to deal with this.

"The world is much more of a global village when you talk about cities."

In education, Mr Schleicher says comparisons between cities are particularly relevant.

"Why is it that city schools in London are so much better than city schools in New York? We should be asking ourselves that question."

The OECD's figures show how the economic activity of metropolitan areas account for a disproportionate slice of national wealth. In France and Japan, 70% of GDP growth between 2000 and 2010 was attributed to their big cities.

And there are forecasts for even more urbanisation, tipping even more of the economic strength into these city states.

The metropolitan areas of Mexico City, Delhi, Shanghai and Tokyo already have populations above 20 million, bigger than most European countries.

The streets of Manhattan: New York has a bigger economy than many individual countries

The report also shows how ideas spread between mega-cities - and how much they have come to look like one another.

It tracks how brands such as Starbucks, H&M and Zara went from operating in relatively few countries in the early years of the century, to being almost everywhere a decade later.

The pressures on urban transport are also shared - and so often are the responses.

There was once only one urban metro system, the London Underground, which began in the 1860s, at a time when Britain's entire population wasn't much bigger than modern-day Shanghai. Now there are more than 100 operating in 27 of the OECD member countries, part of the fabric of highly urbanised areas.

Bike-sharing schemes, launched in Copenhagen in 1995, have spread in 20 years to more than 600 cities around the world - and the biggest are now in China. In Hangzhou alone there are around 80,000 bikes hired out.

The modern mega-city is also intensely international. Whether it's food, languages being spoken, local media, the multicultural mix of people, the rapid flux of money, ideas and fashions - these world cities are increasingly unlike anywhere else within their own countries.

They've developed their own cultural and economic micro-climates. Take a London bearded hipster and he might be more at home in Manhattan than a post-industrial part of his own country.

The OECD raises the question about whether such cities are "now the most relevant level of governance, small enough to react swiftly and responsively to issues and large enough to hold economic and political power".

How do schools in inner London do so much better than schools in New York?

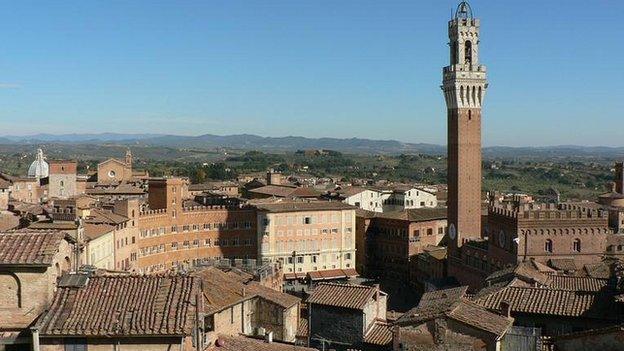

It stirs echoes of the long history of city states, like Italian cities during the Renaissance, with wealth and creativity operating within civic fiefdoms, rather than national boundaries.

The 2016 global trends report provides some other fascinating snapshots of modern living.

Belgium and Japan are the most urbanised countries in the world, with the UK above average.

Smoking tobacco is in decline across all developed countries apart from Greece, where consumption is higher than in 1990, perhaps raising questions about the economic crash.

Suicide rates have either fallen or remained stable across most of the developed world, but the United States and South Korea are exceptions, where the rates have risen compared with 2000. The UK has one of the lowest suicide rates.

Siena's skyline: Will there be a rise of city states like in Renaissance Italy?

Levels of household debt have risen in almost every industrialised country, with the two exceptions being Germany and Japan. Denmark has the highest level of household debt, with the UK in the upper half of the range.

So would the problems of national governments be better addressed at a more local level?

Mr Schleicher says it's the great global cities where many of the big contemporary questions are sharpest.

In such diverse cities, what are the values and identities that need to be promoted or rejected? How do we respond to widening extremes of income inequality? How do we prepare young people for such a shifting jobs market?

What does it mean to be an individual in a huge city shaped by the unpredictable trade winds of a global economy?

Living in a mega-city doesn't necessarily make us feel like mega-citizens.

As the OECD guru asks, how do we make people "feel safe and at home in a city that changes rapidly around them?"

Your comments: Are cities the new countries? Have mega-cities become more like each other than the rest of their countries? And should cities have more autonomy and become like city states?

If we were to start from scratch, we would not create the government structure that we have. Governance is very difficult to change - revolution is the only sure way, as history tells us. Undoubtedly, nation states have been successful but mainly through their ability to carry out warfare. Their days are numbered. Global companies, as well as cities, challenge nation states in terms of economic size.

First question: what is the purpose of government? If it is generally to keep individuals safe and happy, then structures are needed to handle issues at different scales. Globally, to handle issues of nation states, mega companies and cities. Small to be intelligent and responsive to local issues. Perhaps vertical to handle issues of a particular type, such as environment.

I won't live to see significant change but, with the past as our guide, it will be painful. Alan, Lanark

When Norman Mailer and Jimmy Breslin proposed to make New York City a separate country in their mayoral and vice-mayoral campaigns of 1969, then-Hunter College President Donna Shalala countered, in a front-page article in "New York Magazine" that a city cannot have sovereignty if it does not control its water supply. New York City's water supply then and now extends 150 miles north of the city into the State of New York. She cited the example of the constant threats of water supply disruption that the then-British Protectorate of Hong Kong was then facing from the People's Republic of China which harbored the Protectorate's water supply. Michael, New York

Climate change, earthquakes and even volcanoes. The fate of cities is not pretty, especially if you also factor in that the planet is vastly overdue for a large pandemics and antibiotic resistance that will crush super cities. Rudy, Victoria, Canada

The municipal level is becoming in more and more cities the level where sustainable policies and practices can be successfully implemented. This level is also where bottom up initiatives of residents meet with top down policies and funding. Cities are already, partially autonomous states as their population and infrastructures many often exceed the countries in which they are located in. International cooperation, on a municipal level, may often enable bridging over political, social and environmental issues which states policies are not able to. Gil, Jerusalem

In the final analysis Cities are the ultimate parasites. They produce nothing edible, cannot feed themselves yet demand food from the 'country'. In return the countryside gets nothing tangible except taxation and control by City-Dwelling Governments. The Urban puts demands on the Rural, the Rural feeds and sustains the Urban. Without the country farmers the cities of the world would die of starvation.

About the only thing a city does is to push bits of paper round in circles, and consume everything. Oh, and start wars of course. George, Redruth

Pierre Mauroy, order Mayor of Lille and French PM, proposed that this be done years ago. He also suggested a global network of cities should be set up to make the most of the opportunity. Flo, Cheltenham

I have lived all my life in the same tiny rural English village and feel as disconnected from London, though it is only about 120 miles. It seems that it has more in common with New York (which I visited last year) than any other city I have ever been to in Britain. I may sound like a confused yokel but I have been to Berlin and Budapest, Paris, Hong Kong and Barcelona and they all seem as strange as London does to me. They have underground trains and skyscrapers and shops specifically aimed at tourists, it's downright weird. The thought of someone buying a property to sell it for more, with no thought of anyone living in it, or cafes that sell breakfast cereal (let alone at a tenner a bowl) is as odd to me as the customs of another continent.

It doesn't seem as if London has much in common with Norwich at all, and even less with somewhere like Inverness or Minehead. We are neighbours, yet worlds apart. Will, Norfolk

Historically, in most of the world, cities were the political structures and their "countries" were defined by the extent of their political, military and financial influence. The idea of countries we have now, with lines on a map defining the edges, is a modern, European one, fraught with problems because it ignores the disparate characteristics within the totally artificial and often illogical borders. Vince, Croydon

What do you call a city that owns enough arable land to feed itself? A country! Paul, Oberheimbach, Germany

I'm in Osaka - while Tokyo was a small fishing village 200 years ago - Osaka was maybe the first capital and has been a city for maybe 1,000 years - it's huge - with population around 17 million for the conurbation with Kobe and Kyoto - and - the streets are spotless - you won't see dropped rubbish anywhere - just tonight I saw a small shopkeeper with broom and detergent scrubbing the footpath outside his shop. Driving my rental car I had to watch out for bicycles and pedestrians all over the road - they just own the street - cars better take care ! So I'm thinking - these people know how to run a city - and have been doing it for maybe a thousand years. Frank, Australia

If cities are to become states then they need more than water and food. They need to be clear on what they stand for.

If we look at the Dutch city states in the 16th and 17th century, history shows that they could not do things on their own, the trade they brought in from overseas needed to be trade the people down the rivers of Europe in order for the city states to earn money and feed its inhabitants. And they actually, after throwing out the Spanish rulers, formed the first republic, without a king in a time where Europe was ruled by kings and emperors.

To me cities should be clear in their communication on what they offer, a city like Copenhagen (where I was born) says it wants to be the greenest city, Amsterdam claims to have the most bicycles, San Francisco is the city of the free spirit and development of software, etc. I am not opposing the current development of cities into kind of 'states', but we the people need to be part of the development and evolution. Michael, Amsterdam

Surely this is to be expected. Since the grand empires of the early 20th century, more and more countries are being created or gaining independence. Compare this to the Greek Empire under Alexander the Great which slowly broke down into smaller countries and city states until a new empire grew in the Roman empire, which again shrunk. Our world is in a period of empire break down. And with the tendency of history repeating itself, who is it to say in 200 years time, the city state of New York controls the American west coast, Caribbean and parts of south America? Gareth, Colchester

- Published20 March 2015

- Published21 September 2015