Can China keep its new city dwellers healthy and happy?

- Published

Earlier this year, I told the story of Xiao Zhang, an ordinary Chinese woman who witnessed the village where she grew up morph into a huge, modern city, and her fortunes transform. But the effects of China's lightning-fast urbanisation has left those in charge with formidable challenges.

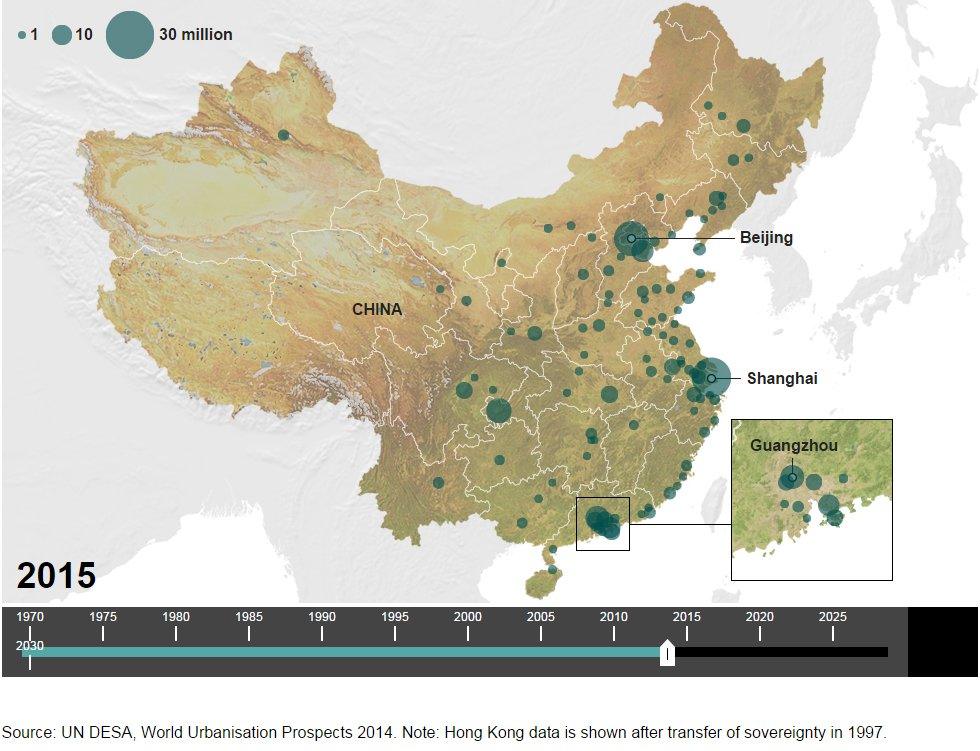

China has tens of thousands of stories like White Horse Village, the settlement where Xiao Zhang was born. The country's urbanisation is the biggest and fastest in history and it's by no means over. By 2030, China's cities will house close to a billion people, that's 70% of the population.

The speed of this transition is also breathtaking. In just 30 years, China has gone from 20% urbanisation to 54%, a journey that took Britain 100 years and the US 60 years. Already there are more than 100 cities in China with a population of more than one million people, compared with only nine in America.

Behind the numbers are hundreds of millions of individual stories just like the ones I covered in White Horse Village.

White Horse Village and Xiao Zhang

In 2005, Carrie Gracie began to chart the transformation of a rural community in White Horse Village, China

The settlement was being developed into a city as part of China's programme of mass urbanisation

Xiao Zhang, pictured, left school at a young age and worked on the land with her parents, before moving to Beijing

She is one of millions who have left behind a hand-to-mouth existence in subsistence farming, and found better economic prospects in cities

In many ways, this has been a success story. The aim was to raise hundreds of millions of farmers out of poverty by giving them urban jobs and turning them into a nation of consumers who would fuel China's internal economy.

And many one-time farmers have embraced the chance to escape a life working in the fields and now enjoy access to housing, healthcare, education and even, in some cases, the luxuries of a personal car or foreign travel. Such things would have been unimaginable to previous generations for whom survival was an ever present challenge.

This success story finds visible form in a new urban landscape of skyscrapers, highways, subways, high-speed rail and airports.

"In the past 30 years we turned farmers into factory workers, triggering massive gains in productivity and hence growth."

So says Premier Li Keqiang, insisting that urbanisation remains a gigantic engine for growth,

"The greatest potential for expanding domestic demand lies in urbanisation."

Certainly China's new cities now crystallise most of the challenges that matter to the country's future - not just the economy, but the environment, politics, health, education and quality of life.

But the successes of China's urban adventure have been matched by equally great failures. The test now is to avoid repeating the mistakes and to make the next chapter for China's cities better in the interests of the one billion people who have to live in them.

The government acknowledges as much. In 2014 it published a plan for China's urban future which admitted to the problems of pollution, urban sprawl, congestion and social tension.

Most of the world's worst air is in China's cities.

In fact, air pollution is now a bigger killer than smoking, according to a study from Greenpeace and Peking University. In one year alone, and for only 31 cities, they concluded air pollution had brought 257,000 premature deaths. And for China as a whole, the Global Burden of Disease Study estimated that in 2010 air pollution contributed to 1.2 million premature deaths, external.

The problems of polluted soil and water are less visible but possibly even worse.

Former Chinese premier Wen Jiabao once described China's water problems as a threat to national survival. About 300 million people drink contaminated water every day.

North China's cities are dangerously short of water. The capital Beijing for example has dropped below the United Nations "absolute water scarcity threshold" to face worse conditions than some parts of the Middle East.

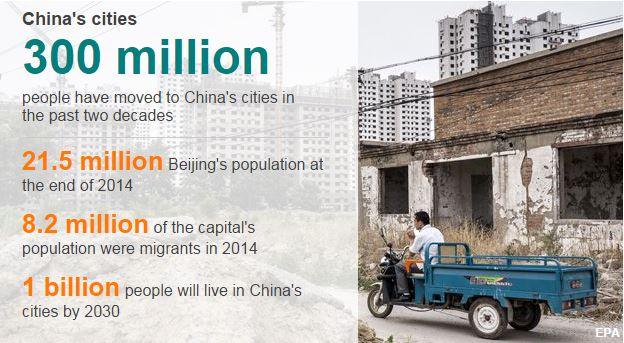

China's cities

300 million

people have moved to China's cities in the past two decades

-

21.5 million Beijing's population at the end of 2014

-

8.2 million of the capital's population were migrants in 2014

-

1 billion people will live in China's cities by 2030

Resulting over-extraction of groundwater means that many of China's new cities are already sinking, which in turn threatens every new thing that has been built from high-rise buildings to high-speed rail.

So the government has embarked on the world's biggest water transfer project, to move nearly 50 billion cubic meters of water every year (more than there is in the River Thames), and to deliver it more than 4,000km away, across roughly the distance between the east and west coast of America. Another way of looking at it is they are planning to move the equivalent of half the Nile River from Cairo to North Syria.

This highlights the strengths and the weaknesses of China's approach. It can marshal political will, expertise and resources to deliver huge iconic projects. But it finds it much more difficult to tackle the problem at source, which is that China's cities waste water just as they waste every scarce resource. Here politics and governance come into play.

How China has changed - in numbers

The BBC tells the story of China's economic growth and mass urbanisation - in pictures, interactive infographics and video.

China's cities consume too much water just as they consume too much energy, land and even clean air, because none of these resources are priced properly in open transparent markets.

Take land. It is a very scarce resource in a country which has more than 20% of the world's population squeezed on to 7% of its habitable surface. But in the process of urbanisation farmland is grabbed from farmers at artificially low prices and sold on in cosy deals between local governments and real estate developers.

In some areas, land sales make up perhaps half of local government revenue. Quite apart from the fact that these land seizures often involve government-endorsed violence, in which hired thugs beat up farmers, the outcome is that China's cities get American sprawl and a rush for private vehicles rather than densely packed communities maximising energy efficiency and public transport.

The World Bank estimates that building denser cities would save China $1.4tn from a projected $5.3tn in infrastructure spending over 15 years.

Chinese citizens get little say in how their cities are planned, built or run.

In the city that has supplanted White Horse Village, called Wuxi New Town, the Urban Development Bureau has a vast model which shows the different stages of urbanisation planned for the entire valley.

But none of the farmers we've met in 10 years of reporting there has ever been invited into the building to see that model, let alone to discuss the blueprint for their future.

China's one-party communist political system is firmly top-down and patriarchal when it comes to city planning. Officials firmly believe they know best what is in the interests of their communities.

But lack of transparency combined with widespread corruption mean that trust is low and often with good reason. In the most notorious cases, urban water supplies have been contaminated by toxic spills or dangerous chemicals stored near residential areas.

For reasons of political paranoia, government discourages the growth of the kinds of non-governmental organisation that might help urban citizens to voice and defend their own interests. It has also made it difficult for citizens to pursue public interest litigation against local government or heavy polluters.

How long China's new urban classes will put up with this is unclear. But their satisfaction is now key to political stability.

On top of questions of environmental safety, food safety and quality of urban services, those who now own property are as obsessed by the value of that asset as the middle classes anywhere. They worry about what is happening to prices, and any sudden fall in prices might trigger not just a financial crisis in China but serious protest.

Just such a political shock is the threat that keeps China's leaders awake at night. But a more fundamental problem for the future of China's cities is migrants.

Perhaps 300 million people have moved into the cities in the past two decades and migrants now make up perhaps a third of the urban population. At the end of 2014 for example, Beijing's population was officially 21.5 million of which 8.2 million were migrants. But most are second-class citizens without the permanent residence rights which would give them access to education, healthcare and social services. Even when they try to set up their own schools and kindergartens, these are often closed down to discourage more incomers.

Migrants suffer discrimination in every area of city life from jobs to housing to abuses at the hands of police.

Not only is this a profound social injustice, it produces enormous costs. Families are split up and - as in the case of Xiao Zhang, the protagonist in my White Horse Village story, and her husband, Changsheng - marriages are strained.

The village that time forgot

She spent her childhood working in the fields, feeding the family's pigs. The destruction of rural China became for Xiao Zhang a liberation - and an opportunity. Carrie Gracie tells the story of how her life changed as much as her country.

Perhaps 70 million children are "left behind", entrusted to relatives or neighbours or rural boarding schools when their parents migrate to cities for work. The most notorious outcomes have been children dying in accidents, committing suicide or falling victim to sex abuse at the hands of those entrusted to take care of them.

But beyond the headlines, the cost to left-behind children in terms of emotional and educational neglect is immense.

Migrants who move into cities need the same rights to housing, healthcare and education as other city dwellers and by putting off this problem and then tinkering at the edges, the government risks failing hundreds of millions of its citizens, present and future, for fear of offending a vocal vested interest.

The government is now beginning to offer migrants residence rights in smaller cities, but as economic growth slows, the best wages are still in the megacities like Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou.

The danger is that small cities such as Wuxi New Town turn into ghettoes of joblessness, unsellable apartment blocks and empty highways. The challenge is to make these cities viable and turn their existing inhabitants into contented middle-class consumers at the same time as absorbing 300 million more over the coming 15 years… without further wrecking China's environment.

We all have a stake in the success of the project.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.