Graduates stuck in pay freeze permafrost

- Published

Graduate earnings have been stuck for a decade - even without taking into account rising fees

If graduates are feeling like they never get any better off, despite having a degree, maybe that's because they really are getting poorer.

The latest official statistics show that the long ice age of wage stagnation is grinding on - and that graduate earnings have been in a deep freeze stretching back for the past decade.

Since university tuition fees in England rose to £9,000 there have been recurrent questions about whether it's still financially advantageous to get a degree.

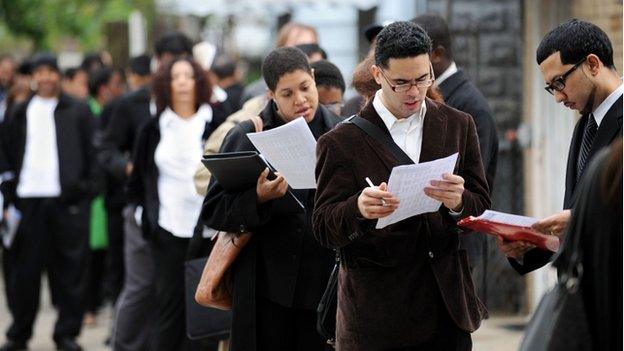

The Department for Business, Innovation and Skills has published its latest figures on the graduate labour market, external - and it shows that graduates are still getting a career benefit.

Graduates have faced years with their pay frozen or falling in real terms

They earn more on average than non-graduates and are much less likely to be unemployed. Postgraduates earn even more and those with higher grades of degrees are paid more than those with lower.

None of that might seem particularly surprising - although there is a slightly worrying rise in graduates in non-graduate jobs.

But the big backdrop - so big that it's sometimes not seen - is the long-term flatlining in earnings. Employment levels have picked up towards pre-recession levels, but pay is still under a layer of permafrost.

The latest graduate earnings figures track median salaries back to 2006. There was a slight upwards nudge between 2006 and 2008, for young and older graduates - and since then barely a flicker.

Graduate Labour Market, 2015

Graduate unemployment: 3.1%

Non-graduate unemployment: 6.4%

Young graduates: 56% in high skill jobs, 31% in medium and low skill jobs

Young non-graduates 17% in high skill jobs, 54% in medium and low skill jobs

Median salary for young graduates: £24,000 (£31,500 for all ages)

Median salary for young non-graduates: £18,000 (£22,000 for all ages)

Source: BIS

What is really tough about these figures is that they are not real-terms numbers, taking into account inflation. These are salaries in cash terms.

A young graduate in 2008 was typically earning about £24,000 and in 2015 a young graduate was still typically earning £24,000.

Apart from the rising costs of bills and underlying inflation, think about the other extra factors hitting graduate finances. They will have £27,000 in tuition fee debt, not to mention sky-rocketing rent and property prices. More money is going out, without any more going in.

Across the whole graduate population, there has been a similar glacial freeze in earnings. The typical salary of graduates in 2015 was £31,500, about £500 more than six years earlier.

Employment rates have recovered but pay has failed to increase

Before everyone starts shouting at the computer at the same time, yes, that £500 won't have covered all the extra costs facing a family over the past six years, particularly if some of them are helping their own children through university.

The BIS department only publishes these figures in cash terms - and it means that in real-terms, once inflation is added, pay rates would have gone down.

The Centre for Economic Performance at the London School of Economics has described this stagnation in earnings as unlike anything since the 1920s - with an estimated 9% real-terms drop in average earnings since the recession.

Behind these figures, across a decade, will be an awful lot of frustrated people, who will have hoped to have been earning a little more and to move to a bigger house or to have enough extra for a holiday with a growing family.

Graduates remain much less likely to be unemployed

This pay-rise drought stretches across the last years of the Labour administration and through the coalition and into the current government.

And it challenges a post-war political system, in the United States and western Europe, built on the idea of rising living standards.

The stalled earnings have come alongside the politics of anger and resentment, caustically burning away at establishment politicians.

It isn't helped by a new class of the super-rich turning their pay packets into lottery wins, such as the BP chief's 20% increase to £14m per year.

And maybe the media's focus on the extremely rich and the extremely poor has caused a blindspot for the vast bulk of people in between.

The politics of anger: A scuffle at a Donald Trump rally in Ohio

These latest UK government figures show that graduates are still ahead in the jobs market.

Universities minister Jo Johnson says these latest figures show that "graduates continue to benefit from higher employment rates and earnings. More students than ever before, including from disadvantaged backgrounds, are achieving their dream of a university education".

But the jobs figures also cast a light on non-graduates too.

They show that an increasing number of graduates are working in non-graduate jobs - and that might be seized upon as evidence that there is less incentive to go to university, if you're going to end up working in a low-skill job.

Graduates have faced questions about whether their degree is worth the cost

But a closer look at the evidence shows that it's getting even tougher for those without a degree.

If you take the whole workforce, across all age groups, 21% of those non-graduates are in high-skilled jobs. Not having a degree hasn't been a barrier for them.

But among younger non-graduates, aged up to 30, this has fallen to 17%. It's harder for them to get into high skill jobs than their parents - and they are increasingly likely to be concentrated in low and medium skill jobs, or not working at all.

The figures also reveal something of a qualifications arms race.

Those with postgraduate degrees have the kind of benefits that once accrued to those with first degrees. They are likely to earn considerably more than either graduates or non-graduates and can be very confident of entering high-skilled careers.

Graduates have kept ahead in earnings, but it's a race where everyone is running up a down escalator.

- Published14 February 2016

- Published1 February 2016

- Published21 May 2014