University of Kent contemplates non-EU future

- Published

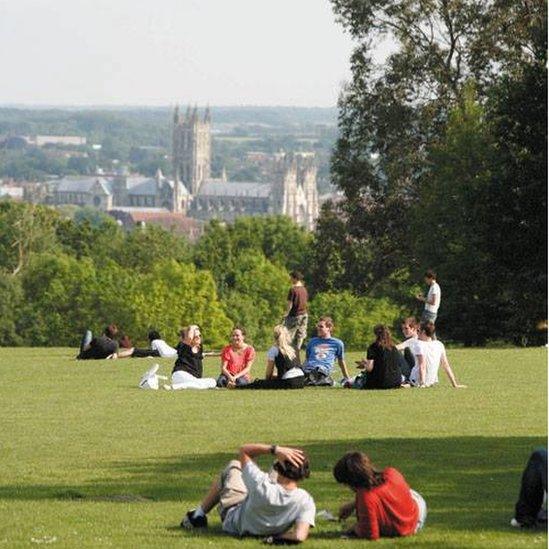

The University of Kent is proud of its European links

The University of Kent is closer to the Continent than any other higher education institution, and it calls itself the "UK's European university", so, post-Brexit, what does the future hold?

Canterbury, the place where a Roman monk called Augustine came to introduce a new religion from the Continent almost 1,500 years ago, is perhaps a fitting place for a university that prides itself on its European outlook.

A quarter of the workforce comes from the EU, while 14 % of undergraduates and 18% of post-graduates also come from mainland Europe.

The university has offices and campuses in Rome and Brussels, and most students do at least some study in another European country regardless of which subject they are studying.

The Department for Business, Innovation and Skills has reassured universities that funding, such as for the Erasmus project, which pays for UK students to study in Europe, is secure at least for the foreseeable future - until the UK formally leaves the EU.

But the great challenge for a university such as Kent lies in the medium to long term - how to be part of Europe without the structures of the European Union to assist it.

The annual barbeque is a morale-boosting, end-of-term thank you for teaching staff.

Exams are over, and the summer holidays are yet to begin.

Funding concerns

Usually it's a light-hearted affair - but, this year, vice-chancellor Dame Julia Goodfellow moved among teachers and researchers trying to reassure them about the future.

As the president of Universities UK, Dame Julia is heading up talks for all British universities with the Department for Business Innovation and Skills as they try to work out a way forward.

She has already had one meeting with the Universities Minister, Jo Johnson, but says that she and her fellow vice-chancellors will have to find different ways of working now that the nation wants out.

Her biggest concern is around research funding.

"We really want the government to start negotiating as soon as possible so we can stay in some of these big research networks," she says.

"It's not just the money, it's actually the links with all the best minds in Europe, the really big collaborations, especially the ones in medicine, looking at really big medical problems. We want to continue to be part of that."

She also says the political uncertainty is unhelpful.

"Just going round the university, talking to people - it's the uncertainty that is getting them down," she says.

"Europe has not gone away, but we are looking at a new positive way of working with Europe"

Canterbury has long had close links with the continent of Europe

Alicia Marzoa, 24, a graduate from Spain, has a contract with the university until August 2017.

But when that expires, she may find she has to apply for a work visa to continue to live here.

She says: "Maybe I'll have to get a visa, maybe, after my contract ends, my situation is unknown, maybe I'll have to leave."

For others, the changes brought by the Brexit are far more immediate.

Ray Lawrence is a professor of Roman history and runs field trips and study at the Kent Centre in Rome.

"The immediate impact is that sterling has dropped against the euro," he says.

"So anything we do in Rome is going to cost us more.

"Our field project this month has cost more than it did last month.

"The effect on our students going next year is that our accommodation costs are going to be a bit more.

"I'm at the stage in my career where I should be applying for a £2.5m European Research Council grant," Prof Lawrence said.

"It would go in the cycle of the next three years, so who knows where that sort of funding will come from in the future?"