What will Theresa May's new grammar schools look like?

- Published

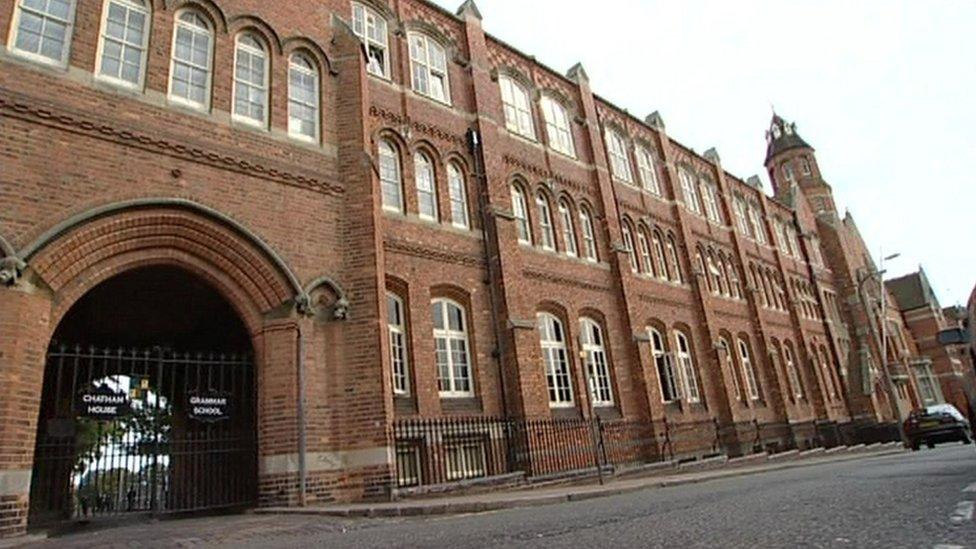

Grammars have often been referred to as engines of social mobility

As the prime minister sets out plans for a new wave of grammars and selective schools, we ask how they might look.

Why is Theresa May setting new conditions for new and expanding grammar schools?

For any new wave of grammar schools to be palatable to a broad section of MPs and peers, Mrs May has to tackle head-on claims that they have become the preserve of pushy, middle-class families.

They need to become the engines of social mobility that they were once seen as.

Following the ban on new grammar schools in 1998, the fight for places, especially in areas where there are just one or two schools, has become more intense.

And this has led to wealthier families with the ability to pay for tutoring and preparation for the 11-plus exam - a set of tests very different from the usual ones taken by primary pupils in England.

Research suggests grammar schools have just 3% of pupils from very poor backgrounds - those on the pupil premium who are basically from families in receipt of certain benefits or earning less than £16,000 a year. Nationally, 14% of pupils are in this category.

Even the chairman of the National Grammar Schools Association, Robert McCartney, says: "They will have to introduce some conditions that will prevent these schools being swamped by families with money."

Hence the new requirement for any new selective school/grammar to take a proportion of disadvantaged pupils, establish a "high quality, non-selective free school", set up or sponsor a primary feeder school in a deprived area or sponsor an underperforming academy.

How are grammars currently trying to broaden their intake?

Grammar school heads have been talking to the Department for Education for some years about the ways in which they might do this.

Of the 163 grammar schools in England, more than 70 are planning to give some form of priority to disadvantaged pupils from next year, says Jim Skinner of the Grammar School Heads Association.

This year, it is about 30 schools.

This is most likely to be through a quota system based on recent new rules allowing schools to give priority in admissions to children on the pupil premium.

The Schools of King Edward VI in Birmingham, a chain of five schools, has led the way, having just admitted its second cohort of pupils with a quota for children on the pupil premium.

In this case, they have lowered the test requirements for disadvantaged pupils.

This may be the way it goes in some areas with a patchwork system of selective and non-selective schools.

But as the law stands this method will serve only the very poorest of families.

For it to go further and include a broader range of low-income families, another change in the admissions code will be required.

However, in areas where the local authority administers the 11-plus test, the council could decide to prioritise low-income children, potentially by broadening the ability range that might secure a grammar place.

Areas such as these are sending between 20% and 25% of their most able children to grammar schools.

Currently, there is also a system of head teacher review in some selective counties.

This is where primary school head teachers put forward a number of disadvantaged children who may not have done well enough in the test, but who they feel show promise.

So what is different in Theresa May's proposals?

The prime minister's plans look set to formalise steps which are already under way in some grammar schools, and indeed the wider education system.

It is not yet clear how a poor but bright pupil quota system would work, but it is clear from existing examples that there may be a need to lower the pass mark for entrance tests for those from poor backgrounds.

This is because as they tend to have had less of the advantages in early life they are likely to fall behind wealthier peers.

They are also unlikely to have received the same kind of intensive tutoring for the 11-plus that wealthier children have received.

So we could see the same kind of system that some universities use to ensure brighter students from poorer backgrounds with academic potential are not shut out.

High-performing schools converting to academy status are already required to work in partnership with struggling schools, and many head teachers do this voluntarily.

But proposals for new or expanding grammars to establish or sponsor a non-selective academy or free schools may tie selective schools into the wider system in a way they have not been previously.

How did the grammar school system of the past work?

The 1950s were without doubt the halcyon days of the grammar school system, with bright children from poorer backgrounds fast-tracked into schools thought suitable for their academic ability.

Pupils who passed the 11-plus exam were destined for university and better jobs, while those who failed went to secondary modern schools and trod a path towards less celebrated professions.

The system covered the whole of England until the mid-1960s, when the Labour government ordered local education authorities to start phasing out grammar schools and secondary moderns.

They replaced them with a comprehensive system - where children of all abilities were to be taught together in the same schools.

This phasing-out happened at different paces, and a handful of local authorities decided to keep largely selective systems.

In 1998, Labour ruled out the creation of any new grammar schools, and limited any expansion in selection within other types of schools.

What is the picture today?

The reach and extent of grammar schools today is very patchy - a legacy from the different responses to the call for comprehensive education and the fact that many grammars converted to independent schools.

In total in England there are 163 grammar schools today - but more than two-thirds of England's 150 local authorities have none at all.

And the areas that do have at least some grammar schools tend to be in more affluent parts of the south of England.

Areas such as Kent, Medway, Buckinghamshire and Lincolnshire have selective systems where the 11-plus test is usually administered by the local authority.

Children either pass the test and get into a grammar or they do not.

But areas such as Gloucestershire, Trafford and Slough have a mix of selective and non-selective secondary schools.

Some London boroughs have one or two grammar schools, where the 11-plus test is administered by the school itself.

The Weald of Kent school is being allowed to open an "annexe" in Sevenoaks next year

Getting a grammar school place in these areas is particularly competitive, but overall there are between 10 and 15 applications per grammar school place, according to the Grammar School Association.

In effect, what many schools do is skim off the most high-achieving pupils who sit the test. So if 1,500 youngsters sit the exam, those with the top 150 marks will get in.

Some say the current ban on opening new grammar schools has led to selection on merit being replaced with selection on financial grounds, because middle-class parents can pay for intensive tutoring for the 11-plus.

Grammar schools in these mixed areas sit alongside many more different school types than in the past.

Not only are there "bog-standard" comprehensives - now known as community schools - but academies and schools with specialist subjects that are allowed to select a small percentage of pupils by their aptitude for that subject.

And there are free schools, which cannot select by ability, but can promote an ethos more like a traditional grammar school if they wish.

What about the expanding number of grammar school places?

Following the 1998 ban on the creation of new grammar schools, many of the remaining grammars, responding to demand, have expanded their numbers.

Between 2002 and 2008, the number of grammar school places grew by 30,000 - the equivalent of 30 new schools.

Then, in late 2015, the then Education Secretary, Nicky Morgan, gave permission for the Weald of Kent Grammar School in Tonbridge Wells to open an "annexe" on a site several miles away in Sevenoaks.

This was seen by many commentators as setting a precedent and paving the way for a new wave of grammar schools.

Since then, no others have expanded on to satellite sites, but there are a number of schools, including one in Theresa May's constituency, that wish to do so.

Although the prime minister has ruled out a wholesale return to a "binary system", there is no doubt that an expansion of selective schooling is on the cards.

- Published8 September 2016

- Published26 July 2016